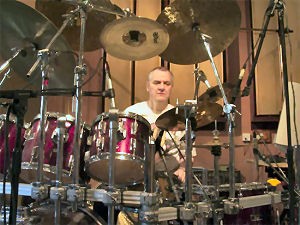

It’s with profound surprise and deep regret that we have to report the passing of our pal and every drummer of my era’s mentor: the great Jon Hiseman.

It’s with profound surprise and deep regret that we have to report the passing of our pal and every drummer of my era’s mentor: the great Jon Hiseman.

Jon died at 03.55 on June 12th, 2018.

I grew up musically around him and he kindly put a couple of great gigs my way which I was too busy to take.

Jon had been on tour with his band JCM in Germany recently when he started getting problems which led to him being hospitalised with cancer of the brain, from which he never recovered.

I have never heard a bad word about Jon, and as you would expect there are a great many heartfelt comments on Facebook which go to show the esteem his contemporaries rightfully held him in.

He was exceedingly well-known in the UK and Europe but somehow not quite so famous in America. They didn’t know what they were missing.

Godspeed Jon and RIP. You raised the bar for drummers!

I’ve sometimes written about the Chinese proverb which states: “when somebody dies a library closes!“. Phillip John Hiseman epitomises the truth of this truism more than most. Just read the following interview piece I wrote two or three years ago and decide for yourself.

-+-+-+-+-+-+-

I went over to Jon Hiseman’s place to interview him a few weeks after he’d returned from a lengthy German concert tour and a couple of months after his biography, “Playing The Band” had been published.

I went over to Jon Hiseman’s place to interview him a few weeks after he’d returned from a lengthy German concert tour and a couple of months after his biography, “Playing The Band” had been published.

To begin at the beginning, I picked up from your biography that you started out with a washboard and brushes, which begs the question – why didn’t you use thimbles like the rest of us?

“That’s a very good question. I had asked my father if I could have a drum kit, because there was a skiffle band that played at the local church that I went to (not for any religious conviction, but basically because there was a youth club there) and they were looking for a drummer. As money was tight and buying one was out of the question, my dad made one for me. It was basically a washboard that came with two legs, which he bolted into the rim of a drum made from an old paint can with book-binder’s vellum stretched across and tied with shoelaces which was held down by a rim cut out of plywood, together with a borrowed Boys’ Brigade cymbal sticking out… all mounted on a kind of stool. Extraordinary! My father was incredibly inventive; he made the whole thing virtually for pennies.

Later, I went to Len Stiles drum shop in Lewisham, announced I was a drummer and asked where the stick department was? They showed me this wall with holes in and the sticks poking out. I bought a pair of Carlton sticks and a pair of brushes (my brush action was completely taken from the thimble action on ‘Freight Train’, (a then current hit by Chas. McDevitt) which I had seen them playing on television… on one of the first of the televised youth programmes.”

That was the beginning of the adventure for you then. So what happened next, did your dad build you another drum kit?

“No, I went with Dave Greenslade to Doc Hunt’s {in Archer Street, Soho} and bought a snare and hi-hat. They were the first real drums I ever owned. The snare was one of those wonderful drums that now they’re trying to reproduce, where you’ve got the little lug, a straight rod with a bobble at each end [tube lugs]. No idea of the make, as someone had spray- painted it white. The rim had these clips over it that pulled down – claws. When you were learning to play rim shots, the claws really damaged the sticks… took great lumps out of them. I might even still have those early sticks kicking around somewhere.”

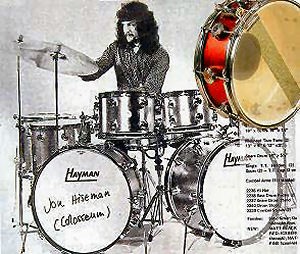

Speaking of sticks, I remember seeing you with Colosseum, playing with your sticks the wrong way round, butt end forward. Do you still play that way?

“No… not at all. In fact I used to have to do that, because on the first Colosseum tour there were no drum mics. We were playing big halls without monitors, the vocals going through the PA and everybody else playing through their amps, with the sound bouncing off the walls. It wasn’t until the last 9 months of Colosseum that we had a proper monitor system and even then it didn’t include the drums. It just meant I was able to hear the vocals and the organ…up until that time it had all been a mystery to me. How we ever played like that, I’ll never know. I often felt powerless, overwhelmed by what was going on around me, especially as the halls got bigger…so I’d turn the sticks around to get more volume. I had to round the butt end of the sticks myself, using a Black and Decker drill with an attachment that drove a sanding disc, as nobody made sticks with the end properly rounded.”

I know in your career you’ve played with some ‘difficult geezers’ and, according to the book, Graham Bond would appear to have been the most difficult of these.

I know in your career you’ve played with some ‘difficult geezers’ and, according to the book, Graham Bond would appear to have been the most difficult of these.

“Yes, Graham was the archetypal sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll guy. Basically he was a megalomaniac, totally unable to see anything around him but himself. He was often in a drug- induced haze and, as I say in the book, there’s no doubt in my mind that he was given LSD to help him through an attempt to go ‘cold turkey’ and he was never the same again. The terrible truth is that, had he been a bigger success, nobody would have cared, because everybody says ‘yes sir, no sir’, but when those around him aren’t even being paid… it becomes even more impossible to cope with those situations.

Graham Bond first heard me playing with The New Jazz Orchestra and said to Dick ‘if Ginger ever leaves, this is the guy to replace him’. Well now, what planet was he on? What was it he heard? There was already a link, though, in that Jack Bruce, who was Graham’s bass player, was also coming along to jazz pianist Mike Taylor’s gigs and rehearsals when I was playing drums for him, on any night off from Graham, as is mentioned in the book. So I’m doing all this stuff, and of course my reputation is going up. Here’s a guy who’s playing with Graham Bond, having taken Ginger Baker’s place when he left. The guy who went on to become one of the biggest drummers in the world with super-group Cream, so it followed that anybody Graham thought was good, must be good. All of which was great for my reputation.”

So he was the baddest of the bad boys?

“For sure… I had to live with utter madness on a daily basis and I managed to handle it for about a year. But, musically it was very exciting… and I was suddenly getting the kind of kudos that I would never have got playing with a dance band, or a less well-known group. The Graham Bond Organisation was the band to see, because Graham was such a lunatic on stage… and when it worked, it really worked. But it was hard, so hard. Of course, it didn’t help that Dick [Heckstall-Smith] was drinking so much that he was oblivious to what was going on. He just stonewalled his way through… didn’t get involved.”

I’m guessing by this time, you must have had a decent drum set?

“I had a double Ludwig kit when I joined Graham, which I bought slowly, piece-by-piece. A double drum kit in those days comprised two bass drums, two top tom-toms and two deep tom-toms, both on the right hand side. It was assembled from three drum outfits of varying sizes. I made a terrible mistake early on by going in to Drum City and buying a 20” left hand bass drum to tie in with a 22” right hand bass drum and quickly realised that this was a total waste of time and money. I had started playing two bass drums in a free jazz context, because I wanted to be able to create these rolls and rumbles, whilst doing other stuff on the toms. Of course, the original idea of being able to play two different-sized bass two drums, each with differently positioned legs, was never going to work and was always going to be difficult to coordinated. So, I had to go back to Drum City to trade-in the left hand bass drum and buy second 22” (at a considerable financial loss!). The problem was, of course, that as you tended to play the right-hand drum more than the left, the right-hand head bedded in and produced a totally different tone to the other one”.

Eventually, in the fullness of time, they brought out double bass drum pedals…this must have helped.

“Of course, every double bass drum pedal that arrived, I played…and I broke them all! They were all completely useless. Finally, Yamaha came out with the only double bass drum pedal that actually works (in my opinion) and three years after they brought it out they changed it…and not for the better. So I now have five or six double sets of the one good version, half of which I bought second hand and I hope these will last me out.”

So what came after the Graham Bond Organisation?

So what came after the Graham Bond Organisation?

“I joined Georgie Fame’s band, which I played with for six months, until he disbanded it after he had a Number One record with ‘Bonnie and Clyde’. His management told him he didn’t need a band any more, because he’d be going around the world for the next couple of years just doing TV appearances, miming with a fake machine gun! The net result of that was…I was out of work again!”

What was it like playing with Georgie Fame?

“I wasn’t the right drummer for him, because I didn’t know anything about funk. I knew about jazz, because I’d gone from classical music to free jazz and on to straight-ahead jazz. I had played with a lot of the top UK musicians, even, at one time, asked for by Roland Kirk to accompany him at Ronnie Scott’s. Unfortunately I couldn’t do it, because of other commitments.

Anyway, it happened that Georgie was looking for a drummer just at the time when I’m not doing anything much. One of my personal friends, Colin Richardson, (also the editor of Jon’s biography) who I’d met when he was manager of The New Jazz Orchestra, happened to be working as Georgie Fame’s booker at the Rik Gunnell Agency, so mentioned me to Georgie, saying ‘what about Jon Hiseman… he’s just left Graham Bond’. At the time, I’d never heard King Pleasure or Mose Alison and thought that Georgie was playing original material… and of course I had no idea what drum parts he would expect me to play.”

Was Mitch Mitchell in Georgie’s band before or after you?

“No, I think he was before me. I was a great fan of Mitch… I thought he was an astonishing drummer. I heard him with Jack Bruce at the Lanchester Arts Festival in 1970 and thought he was just fantastic. Unfortunately, fame and success can go one of two ways… and, if it goes the wrong way, you die. I had also seen him towards the end of his time with Jimi Hendrix… it was at some big university gig and Jimi was starting every number with the band, then, a couple of choruses in, he would stop them and play solo. Mitch wasn’t even close to making it on that gig. He just seemed somehow lifeless… when he wasn’t playing; he was slouched dejectedly over the drum kit. When I later bumped into him in the lift, he could barely talk.”

When did ‘Variations’ rear its head?

When did ‘Variations’ rear its head?

“Well, after Colosseum and Tempest, came Colosseum II. (The time line is basically Colosseum: 68 – 71, Tempest: 72 – 74 and Colosseum II: 75 – 78.) It was a very difficult operation financially and we were always desperate for money. In fact, some of the toughest parts of the book are actually those covering Colosseum II. Anyway, we had just made, what I consider to be, one of my best albums: ‘Electric Savage’, which was about to be released by MCA. They happened to be playing it in their offices the week prior to its release, when Andrew Lloyd-Webber dropped in and, on hearing it, asked who it was. It turned out that he was looking for just our kind of musicians to play on his next project.

Soon after, I got a call from him, saying, ‘you don’t know me, but my name’s Andrew Lloyd-Webber. I was in the MCA offices when they were playing your record and this is exactly the sound I’m looking for.’ Now, Andrew, it seemed, always had a problem with rhythm sections, in that, he couldn’t explain to them what he wanted, nor did he know how to write it. The orchestral stuff wasn’t a problem… from the keyboard, he could either tell an arranger what he wanted and then he, or the arranger, could write it. Anyway, he had this idea for an arrangement of ‘Variations on a Theme’ by Paganini, featuring his brother Julian on cello, but the problem was, as always, the rhythm section. What were they going to play? Apparently, when he heard ‘Electric Savage’ he immediately knew that this was the sound he wanted. That’s when he rang me and asked, ‘would your team be willing to do it?’ So, I went to his flat and he played it through for me, but at the end of the 45 minute performance, although I was aware that the tunes were very strong, I didn’t remember much else.”

So, next I told the boys about it, saying: ‘It’s Andrew Lloyd Webber and he’s paying real money! We go in the studio in two weeks!’ Then, three days before the first rehearsal, I got a phone call from David Land, Andrew’s manager. He said Andrew needed a flute player who could also improvise on the saxophone… do you know anyone who can do that? So I said, ‘of course’! When I later introduce my wife Barbara as the woodwind and saxophone player… he gave me a look which spoke volumes. He obviously thought it was a ‘row-in’. Well, what would you think? But, within half an hour he was all over her, in fact, he was going to spirit her away… he couldn’t believe it. All her solos and everything else she played on ‘Variations’ and later, ‘Cats’ were transcribed and have been played every night since. Anyway, it was pretty much ‘job done’!

There’s one story I like tell about Andrew. One day, he came to us in the theatre, after rehearsal, and said; ‘We don’t have a big number for Elaine’ (Page). We need a serious song to close the first half, so I’m going home with Trevor Nunn tonight and we’re going to write something. Would you please all come in early tomorrow and we’ll run through it… so she can sing it at tomorrow night’s preview’. We were about three days away from opening night, but we all turned up the next day at 2pm and Andrew sat at the piano and played the new song that begins, ‘Midnight, not a sound from the pavement’, which we worked on until 4pm that afternoon… and so another Lloyd-Webber major hit was born! Andrew could spend just one evening with Trevor Nunn, distilling the words from three T. S. Eliot poems and write a melody like ‘Memory’… I don’t care what anybody says – if you can do that, you’re my man! He deserves his ‘Lordship’ just for that one!”

[The first ‘Variation’ became the South Bank Show’s theme tune for thirty-two years. Right up to the last episode and it was always played in full]

How did the United Jazz and Rock Ensemble come about?

How did the United Jazz and Rock Ensemble come about?

“It came together in a German TV show called ‘Elfeinhalb’ (‘Eleven-thirty’) in 1975. It was one of the first youth shows televised in Germany which included political discussion, (even the German Chancellor took part in an interview about youth matters). Each discussion was interspersed with a piece of music, played by the ‘house band’, formed and led by Wolfgang Dauner, a Stuttgart musician, who was told he could choose anyone he liked to be in it. We (Colosseum) had worked with him as support act – even loaning him a lot of sound gear at one gig, when his hadn’t arrived…something he never forgot. In return, he later invited me to do an album with him. I did the album and then he asked me to come and play on this TV programme.

We used to go to Stuttgart for a week every three months, putting stuff in the can and then they would feed it into the show. The band was an 11 piece jazz/rock group, but the personnel changed every week, except for Wolfgang and I, who were there all the time. After two or three well-known saxophonists had been and gone, Wolfgang came to me and said…‘do you know a good saxophone player?’ I pulled out a picture of Barbara and said ‘yeah, I know this lady’ and he said ‘if she plays like she looks, she ought to be in the band, so bring her next time’. I did… and she became a permanent member of the UJ&RE from that day on!

At some point, the programme changed its name to ‘Golden Sunday’, then after about two years of the programme going out every month, it was suddenly announced that we were going to do a live concert, playing the material that we had been performing in the shows. We had a couple of rehearsals after we’d finished televising, then, on the night of the concert, at least 2,000 people showed up, which no-one had expected! They had to turn 500 people away…it was mayhem! Obviously, all those TV appearances had built up an incredible interest with the public. That success was just the beginning and soon after that they began the publicity for a National tour. The group was quickly dubbed ‘The Band of Band Leaders’ and the next logical move was to record a live album, “Live at The Schützenhaus” in 1977, which went on to sell more copies in Germany than any other German group since the Second World War! It was phenomenal!

They had, in fact, originally sent the tapes to two or three record companies, who all turned it down, so four members of UJ&RE formed their own record company, called Mood Records, which went one to become an extremely successful company. After Colosseum II folded and I joined Barbara’s band, Paraphernalia, we would take it in turns to tour…one year Paraphernalia would tour, the next year UJ&RE would…by which time we would have another album ready. We continued doing this for 20 years, just playing alternate years.

As much as I enjoyed playing with the Ensemble, I have to say that, as a drummer, having spent my whole life looking for people who make me sound great, it was with Barbara that I found that someone special. Playing with her makes me sound as good as I’ll ever sound in my life!”

I read in a 2004 interview that you weren’t originally interested in being a drummer… this is a direct quote…and that you fell into drumming by accident

I read in a 2004 interview that you weren’t originally interested in being a drummer… this is a direct quote…and that you fell into drumming by accident

“That’s actually true!”

When you use the phrase ‘playing the band’, do you mean that you’re playing as the band…not just the drums? Playing for the song…which is something a lot of drummers don’t do.

“I take from what’s going on around me and I have to really feel that there’s a problem, before I will actually create something that isn’t already going on somewhere else in the band. That’s something I did very early on. In fact, whether as a producer or band leader, if I feel something isn’t working…rather than change the drum part to make it work, I’ll get someone else to change their part before I even look at the drum part. Quite recently, I discovered that Benny Goodman used to rehearse the band without the drummer, until they could play a piece perfectly. Only then, would the drummer play the piece with the band… which is a great idea. Buddy Rich used to do the same thing, but of course, Buddy, not being a reader, was working out what he would play. By the time he sat down at the kit, he could play it because he’d actually put the band through it.”

If you’ve only got two days to learn stuff before recording, this must make it a heavy read on your part?

“The problem is…I don’t read, you see. Though, to be more accurate… I can read anything, but I can’t sight-read. My family have always believed I’m slightly dyslexic, which might be a contributory factor. When I read words, I effectively ‘speed read’ and therefore I don’t always see mistakes, because I’m not reading word for word… I never have. I do, however, have a fantastic retentive memory. At one point, I even decided that, for 3 months, I would spend an hour a day on reading practise, but it made no difference. On the other hand I’ve got rudimental drum parts that would make your eyes water… and I can work them out, but I can’t sight-read them. It was problematic with Andrew Lloyd-Webber, because he didn’t know, but I didn’t keep it from him. I kept saying to him…‘Andrew I’m not a reader’. He would just reply…‘Oh dear boy…you just play’.

The scariest time of all, was when we played with the London Philharmonic, Placido Domingo and Sarah Brightman, on a big television ‘special’ filmed before an audience at BBC Television Centre. The producer decided that Andrew should conduct a medley of his hits to open the show. Now, Andrew isn’t a conductor! So I’m sitting there thinking…‘this is going to be fun’! Suddenly there’s a tap on my shoulders and Andrew says: ‘Dear boy, I’ll follow you’. So I had to set all the tempo changes up in a big way and he just followed me, which actually worked out fine, but it was pretty scary, particularly since I didn’t have any parts. But, as I said, I have a retentive memory…I only have to hear something once or twice and I’ve got it. When we got Colosseum together again after 25 years, I could still play all that stuff without even thinking about it. I just knew it, one bar ahead all the time.”

Wasn’t there a story that there was never going to be a Jon Hiseman drum solo album?

“I don’t know about that. In fact, there is a drum solo album… it came out in 1988. It’s called ‘About Time Too’. Actually, it was issued in Germany with a title that translates as: “He’s Hot That Heisman”. It’s a German joke… and all the Germans fall about, but nobody’s ever satisfactorily explained the joke to me.

The best review of it was in ‘Modern Drummer’, where they go on about ‘fascinating this and amazing that’ and then said: ‘Of course, Hiseman is best soloing when he’s jamming along with the other percussionist’… but it was all me! I was playing cow-bell with one hand and had all this other stuff going on around it. To me, that’s the greatest review you could ever get from ‘Modern Drummer’.”

You are, without any doubt, the band leader. Do you think drummers make good band leaders…and if so why?

“Because we’re on the outside…we aren’t musicians and we shouldn’t pretend to be. If you are a real drummer, you aren’t a musician! What you are is a catalyst, both on stage and off. You pull things together and you keep them together…sometimes you have to get the whip out and sometimes you have to ‘pour oil on troubled waters’. That’s what you must do…both when playing and when away from the drum kit. We drummers have an innate ability to do that.”

“One of the things I’d like to say about my biography, which occurred to me as a result of a couple of conversations I’ve had, is this… it’s quite easy to write a book when you’ve met a lot of people and you know a lot of the inside ‘scoop’ on them, but when ‘Playing the band’ was first mooted, I made a conscious decision that it was going to be an honest story about my life, the people I’d worked with and known intimately. It was never going to be just gossip and ‘dishing the dirt’ on a bunch of famous names, just so they could be listed on the back cover. It was a clear and deliberate decision, that, whatever my involvement with them… whether they’d let me down… whatever had happened, I would be completely honest about it. I was not going to get into any ‘naming and shaming’ or malicious stuff. Sure, I know a lot of shit about a lot of guys and it could all have gone in the book, but my intention was to make the book be as truthful as possible about what has been, and still is, a tough artistic life… always trying to beat the system, always trying to make it work against all the odds. Throughout my entire life, it has never been about making money!”

Jon’s biography can be got at http://www.temple-music.com

Thanks to James Cumpsty for coming up trumps.

Bob Henrit