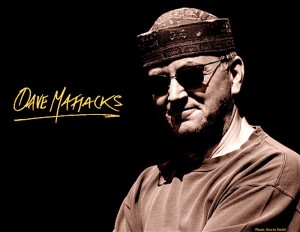

David James Mattacks was born in the London suburb of Burnt Oak on the 13th March, 1948 which unfortunately makes him considerably younger than me. Nevertheless I needed a calculator to work out how long we’ve known one another, and it turns out to be 53 years! The Mattacks family moved around a lot although when Dave was two they relocated to Dartmouth, Devon where they stayed for eight years. Eventually they found their way to Haywards Heath in Sussex via Frome and Slough – places which non-English folk have difficulty pronouncing.

David James Mattacks was born in the London suburb of Burnt Oak on the 13th March, 1948 which unfortunately makes him considerably younger than me. Nevertheless I needed a calculator to work out how long we’ve known one another, and it turns out to be 53 years! The Mattacks family moved around a lot although when Dave was two they relocated to Dartmouth, Devon where they stayed for eight years. Eventually they found their way to Haywards Heath in Sussex via Frome and Slough – places which non-English folk have difficulty pronouncing.

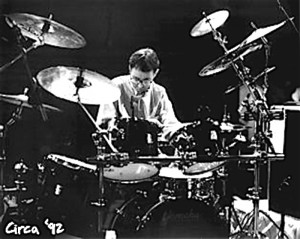

We used to bump into one another at Drum City, in London’s, Shaftesbury Avenue where I was frequently hanging-out while Dave was actually working as a sales-assistant. Well he wasn’t just selling drums, nobody does just that in a drumshop – including the owner. He was also repairing drums and stands, lapping natural drum heads, networking, surreptitiously practising paradiddles on the counter, and probably even making tea.

To begin at the beginning Dave started out on his drumming career with a pair of bongos bought when he had just become a teenager from a second-hand shop – he played these with his mother’s knitting needles [and he remembers playing along with those knitting needles to Elvis Presley’s “His Latest Flame” which, to give a useful time-frame, was released in 1961] Prior to this though he was a child prodigy who. from the age of six, could play any tune he heard immediately on the piano – a useful ability for any musician to have, especially a drummer.

Eventually he abandoned the bongos and bought his first ‘Bitsa’ drum set – albeit one piece at a time. His first acquisition was a ‘Gigster’ snare drum followed, sometime later, by a single-headed Olympic floor tom, then a single-headed bass drum. Once he had these essential pieces he then saved up for a mounted tom. He told me he was 13 or so when he began saving up for these individual pieces of the kit and this endeavour took him 18 months. Once he had all the elements he was ready to rock, and started a band at his school.

As it happens Dave considers that first snare drum to be the worst he’s ever had, although at that time and at that age I doubt whether any of us teenagers would really have known the difference. This was a time when most people including the salesman, extolling the virtues of a drum he was trying to sell, had no idea what wood it was made from and even what affect another genus of tree might make to the sound! Fortunately for the drum-world, Dave’s next snare drum was a Premier! Eventually he made a quantum leap up to a Ludwig kit which was certainly as high as you could go in those days. While I’m on the subject, in the sixties he acquired a couple of snare drums from Vic O’Brien in London’s New Oxford Street which he still uses: a wood shell WFL and a Gretsch chrome-over-brass which he changed the sound of by adding triple-flange hoops.

Like most of his/our generation he was much taken by the drumming of The Shadows’, Tony Meehan and his successor with Cliff Richard, Brian Bennett who were to be seen in Black and White on Television on – what seemed at the time – every Saturday night. But Dave was also becoming aware of jazz drumming and Joe Morello and Irv Cottler in particular (who was the subject of a recent G&S) – in short he was into all the obvious jazz players including of course, Buddy Rich.

Like most of his/our generation he was much taken by the drumming of The Shadows’, Tony Meehan and his successor with Cliff Richard, Brian Bennett who were to be seen in Black and White on Television on – what seemed at the time – every Saturday night. But Dave was also becoming aware of jazz drumming and Joe Morello and Irv Cottler in particular (who was the subject of a recent G&S) – in short he was into all the obvious jazz players including of course, Buddy Rich.

His family were now living in Southend and it was here, by the seaside and the longest pier in the world, that Dave left school. Dave decided he wanted to become apprenticed to a piano tuner and eventually persuaded someone to take him on as a trainee. But having worked away diligently for a year or so, he decided that it wasn’t really for him and he got a job in Ivor Arbiter’s prestigious Shaftesbury Avenue emporium – Drum City . The family were now living near Brighton, in Haywards Heath, which necessitated him making a long and crowded train journey up to London every morning.

Before this, he decided he wanted to take formal drum lessons and took them in Southend from a big band drummer called Johnny Joseph who taught him ‘quick-steps’, ‘fox-trots’, ‘valetas’, ‘cha-chas’, ‘rumbas’, ‘waltzes’ and the like. He also taught him the highly-important strict-tempos to play these rhythms at.

Dave told me in an interview that:

“I knew I had a further facility but didn’t think that this would get me very far unless I got more stuff going on. It wasn’t so much the technique side of it, although the teacher did help me with that but it was more I didn’t just want to be a rock drummer. That was my subconscious thinking.”

These were the last lessons he would take.

Dave’s first big break came while he was working during the day in Drum City and moonlighting doing gigs around Sussex at night. He was in Brighton when a trumpet player of his acquaintance came over to tell him how much he liked his playing and went on to say he had a contract to go on the Mecca Ballroom circuit and was looking for younger players. How was his reading? Dave jumped at the chance thinking the gig would be in a London Dancehall but it turned out to be in Belfast, Northern Ireland, which wasn’t exactly the bright lights of the world of dancehalls. But it didn’t matter to him – he was working. He stayed there for nine months (in the middle of “The Troubles”) and was in his element playing strict-tempo music for ballroom dancers four nights a week and pop music at the weekends. The whole band was moved to Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow where Dave not only celebrated his 18th birthday, he also played on the BBC’s popular weekly National TV show, “Come Dancing”. This really was ‘the big time’ in those days.

Dave’s first big break came while he was working during the day in Drum City and moonlighting doing gigs around Sussex at night. He was in Brighton when a trumpet player of his acquaintance came over to tell him how much he liked his playing and went on to say he had a contract to go on the Mecca Ballroom circuit and was looking for younger players. How was his reading? Dave jumped at the chance thinking the gig would be in a London Dancehall but it turned out to be in Belfast, Northern Ireland, which wasn’t exactly the bright lights of the world of dancehalls. But it didn’t matter to him – he was working. He stayed there for nine months (in the middle of “The Troubles”) and was in his element playing strict-tempo music for ballroom dancers four nights a week and pop music at the weekends. The whole band was moved to Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow where Dave not only celebrated his 18th birthday, he also played on the BBC’s popular weekly National TV show, “Come Dancing”. This really was ‘the big time’ in those days.

After three years that gig came to an end and the band was transferred back to London where they found themselves part of the ‘Holiday Relief Circuit’ replacing other dance bands who were taking a well- earned couple of weeks off. Dave says they played in more or less every dance hall in the Capital including Leicester Square, Croydon, Purley and Tottenham. Dave says he’s certainly played his dues with those Mecca gigs playing seven nights a week from eight pm until midnight with an extra hour on Fridays and Saturdays.

The next thing to come along for him was the gig with a more or less completely new musical form – an ‘Electric Folk’ band which was a genre which hadn’t really used drums before. The band was Fairport Convention and a vacancy existed because their drummer, Martin Lamble, had been sadly killed in a motorway crash at 19 years old.

As Dave puts it:

“I went into Drum City one day. I’d stayed in contact with them because every now and again in Scotland, I’d get a night off and fly down from Glasgow to London for about £25; I’d see my folks and then invariably end up hanging-out in Drum City. I’d stayed in touch with some of the people who used to work there, one of whom was Graham Willard, another was Gerry Evans and also [now] Marillion’s drummer, Ian Mosley. So I went in one day and they asked if I’d heard of a group called Fairport Convention – ” They’re looking for a drummer.” I said I wouldn’t mind going for that. I called and they were looking at drummers in West London – I went along and auditioned. There were about a dozen guys all queued up to play Martin Lamble’s drum kit, I didn’t know anything about them.

Just before it was my turn, this guy walked in and the band went up to him with the – “Oh hi, we didn’t know you were coming, this is fantastic, wonderful!”, so I thought that was the end of that. But I hung around. I should also add that the day before, I did a bit of homework – I went out and bought their most recent album, “Unhalfbricking”, and swotted it. So it got to my turn and we played one of their songs in 5/4 that I’d learnt. I didn’t know anything about the band, we got to the end of it and I said thanks, thinking I was wasting my time. I was about to walk out and Simon Nicol came up to me and said “Would you mind hanging around?”, so I went out to the other room and a couple of minutes later Simon came out and said words to the effect “We’ve had a little huddle, would you like to come back and work with us some more?”.

Just before it was my turn, this guy walked in and the band went up to him with the – “Oh hi, we didn’t know you were coming, this is fantastic, wonderful!”, so I thought that was the end of that. But I hung around. I should also add that the day before, I did a bit of homework – I went out and bought their most recent album, “Unhalfbricking”, and swotted it. So it got to my turn and we played one of their songs in 5/4 that I’d learnt. I didn’t know anything about the band, we got to the end of it and I said thanks, thinking I was wasting my time. I was about to walk out and Simon Nicol came up to me and said “Would you mind hanging around?”, so I went out to the other room and a couple of minutes later Simon came out and said words to the effect “We’ve had a little huddle, would you like to come back and work with us some more?”.

The next thing Dave knew he was in Winchester in a huge house rehearsing with them, five days a week. After a couple of weeks he thought he should ask:

“So, have I got the job?”, and they said “Yeah, sorry, didn’t we tell you? ”. So there I am in Fairport Convention and my knowledge of folk music was a bunch of blokes in woolly sweaters, like Peter, Paul and Mary – that’s about as much as I knew about folk music.”

Now this is where Dave and I agree to disagree because for my money he invented ‘Folk rock’ drumming. There really hadn’t been too much drumming in the newly emerging genre. Characteristically he is much more self-effacing.

“I didn’t really realise, I just responded to it in a way that I thought was musically appropriate. I’ve read some of the things which said I “changed drumming”. Well maybe, although I doubt it, because I wasn’t playing anything brilliantly technically. It wasn’t like I was ground-breaking in an Elvin or Tony way, I wasn’t doing anything that hadn’t been done before, the only thing I was responding to was the musical situation. But I wasn’t changing anything, just playing songs and dance tunes.

One thing some people have made observations about is the reels which are just 4/4 ; what I realised is if I just played them one way it would sound really dull and boring – if I played a 2/4 beat that would sound really corny. So the only thing I came up with was a direct lift from Ginger Baker – I played a double time back beat on the hi-hat [off beat eighth notes ], and then the snare drum on 2 and 4 , and I thought that’s good because it mixes the two feels. That was me just thinking if I combine these two back beats, the whole thing seems to swing. If I play just a regular rock back beat it’s got no uplift to it, it’s ploddy – and if i just do the 2/4 feel back beat, it’s going to sound like I’m playing a Polka!

I was simply thinking if I use that beat that Ginger did, that covers both the bases and that was the end of my thought process about it.”

I was simply thinking if I use that beat that Ginger did, that covers both the bases and that was the end of my thought process about it.”

Dave told me how he was dropped in the deep end of some absolutely unbelievable music.

“I’m learning so much about it and they were playing this stuff and there were odd bars all over the place and I’m thinking this is really cool, really interesting. All these time signatures, dropped beats and bars and I’m thinking ‘This is fantastic!’ I did that for about a year and then the light bulb goes on and I really, really get it, it suddenly makes complete sense. Up until that point it’s been chops, speed, technique, how fast can I play this, can I get this flashy fill in there? Finally I get it. I basically do 180º turn on myself and the whole technique/speed thing stops being the Holy Grail for me.

“I start really appreciating it, I’ve been quoted saying this before and I’m happy about saying it. It’s not meant in a derogatory way but it’s just the difference between Maynard Ferguson and Miles Davis, and the difference, again dare I say it, is it’s an attitude thing. The difference between Neil Peart and Levon Helm, and I just go, almost blindly in fact, towards the Levon Helm way. Then after about 5 or 10 years I come back and learn to appreciate both sides of the story. But when the light bulb goes on, it’s a revelation for me and I utterly get what they’re about. Before that I’ve been responding to the music I’ve been presented with in a kind of literal way. I’m playing it, and hopefully playing it musically but on an aesthetic level I don’t really get it, ; then the light bulb goes on and it’s a really profound moment for me.”

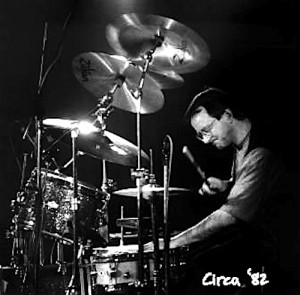

When he joined Fairport in 1969, they had the album out called ‘Unhalfbricking’ with Martin Lamble playing drums, which is the one he’d learnt from, but Dave’s first album for the band was ‘Liege and Lief’ which came out later the same year.

Dave’s first stint with the band lasted for three years and his tenure was eventually broken because he simply had too many sessions on his plate – he also left to briefly join “The Albion Band ” with Ashley Hutchings, Martin Carthy and Simon Nicol – and something had to give. These sessions were many and varied and the list reads like a who’s who of the folk artists of the time.

His work to date has included, (amongst many others) Brian Eno, Ralph McTell, Mickey Jupp, Cat Stevens, Everything but the Girl, Mike Heron, Cliff Richard, Kate and Anna McGarrigle, George Harrison, Loudon Wainwright, Gary Brooker, Elton John, Debra Cowan, Alison Moyet, Jimmy Page, Barbara Dickson, Beverley Craven, Sandy Denny, Jimmy Page, Mathew Fisher, Chris de Burgh, Andy Fairweather Low, Peter Green, Paul McCartney, Kajagoogoo, [a year with] Jethro Tull, and The Proclaimers.

In 1985 he was back in the fold with Fairport Convention where this time he stayed for 12 years .

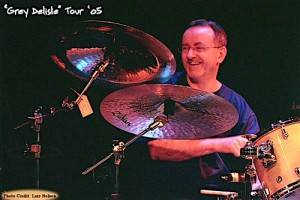

The next big change in his life was upping sticks (pun intended) and moving to America – Mary Chapin Carpenter , Teddy Thompson and Rosanne Cash are some of the artists he’s worked with since the move.

Dave is nothing if not tenacious and once he’s got his teeth sunk into a project like Fairport he tends to hang around. ‘Feast of Fiddles’ is one of these ventures with real longevity. He’s been doing it for 25 years and tours with them every spring in the UK. The band consists of a 5-piece rhythm section and six fiddle players.

Dave is nothing if not tenacious and once he’s got his teeth sunk into a project like Fairport he tends to hang around. ‘Feast of Fiddles’ is one of these ventures with real longevity. He’s been doing it for 25 years and tours with them every spring in the UK. The band consists of a 5-piece rhythm section and six fiddle players.

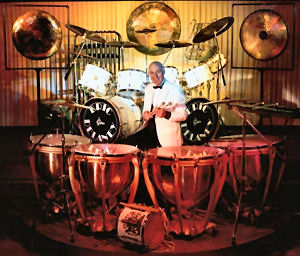

Dave is a Yamaha endorser who doesn’t consider himself to be a drum collector but I’ll leave you to make your own mind up on the subject, gentle reader. He told me the following several years ago when I sold him a deep LA Camco snare drum in ‘Alice Cooper blue’. So the situation has either got better, or worse depending on your point of view;

“At the last count I’ve got about 14 or 15 sets and about 80 snares. Most of this is in my basement in Boston and then there’s a set in London. The kit in London has some snare drums, but the bulk of it is here in the US with me. Out of what’s in my basement I would say ¾ of it gets used every six months or so.”

In his defence, Dave’s isn’t what you’d call a glass-case collection. “They’re all to be played. Some get played more than others, but they all get played, that’s what they’re there for. ” They all sound different and what he’s tried to do is to pare the collection down so he’s not doubling up with anything. Obviously it’s a passion and he says it’s probably beyond reason “But they all get used.”

It’s the same with the Zildjian cymbals – he’s probably got about 200, maybe more. There’s some beautiful old ones, some lovely new ones.

The website ‘All Music’ said he was decidedly a candidate for best folk drummer in the UK. He certainly should be, IMHO he invented the genre although perhaps ‘All Music” should be talking of electing him the best folk drummer in the world!

The website ‘All Music’ said he was decidedly a candidate for best folk drummer in the UK. He certainly should be, IMHO he invented the genre although perhaps ‘All Music” should be talking of electing him the best folk drummer in the world!

My writing partner and friend Nigel Constable went to see him playing some jazz in Worthing recently and was hugely impressed. He sent me a text from the gig talking about Dave’s prowess which ended with the following;

“Versatile bastard isn’t he?”

He most certainly is!

Bob Henrit

©2017 RJ Henrit