Dave Tough was born of Scottish parents in Oak Park, Illinois on the April 26th, 1907. At the time Oak Park was a town just outside of Chicago so unsurprisingly he was ideally placed to become a leading light in the Chicago jazz scene. Since prohibition was still in place there until 1973, moving into Chicago itself may well have been a contributory reason for this, since he ultimately had problems with alcohol.

He began his playing career as a youngster and like many others was influenced by Baby Dodds. He became part of the Austin High School Gang which was, we’re told, ultimately responsible for the ‘Chicago’ style of twenties jazz. Dave Tough was also known as Davey and Davie and he cuts a very dapper figure – there’s at least one photo of him where he looks an awful lot like our own Charlie Watts.

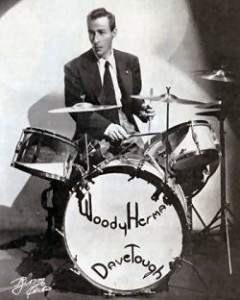

He worked with all the main Dixieland/swing musicians of the twenties, thirties and forties: Bud Freeman, Woody Herman, Eddie Condon, Red Nicholls, Tommy Dorsey, Red Norvo, Bunny Berrigan, Benny Goodman (where he replaced Gene Krupa), Jack Teagarden, Artie Shaw and Charlie Spivak – in short all the giants of the age.

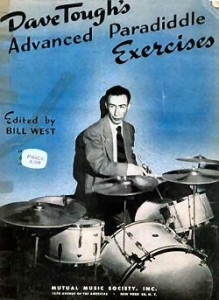

At just 98 pounds, he was always frail and tiny, evidently with physical and mental problems. However none of this showed in his intense and relentless playing and he’s described as a subtle and inspired drummer who hated to solo even though he wrote a comprehensive book on paradiddles.

Perhaps uniquely he’s characterised in an autobiographical novel by a Kenneth Rexroth, a one-time Chicago resident and ‘Beat’ poet (along with Ginsberg, Burroughs and Kerouac); as ‘Dick Rough’ a poet/drummer at an existing Bohemian tearoom called the ‘Green Mask’.

“One night a skinny little boy came in with a whole mess of drums. For once we all realized we had a great artist. It was Dick Rough [Dave Tough], the first and greatest of the hipsters and one of the few really great musicians in the history of jazz. It turned out that he also wrote poetry no better or worse than my own, a precocious kid’s poetry. He and I became friends. In spite of the entire repertory of minor vices which were to become part of the jazz-man stereotype of a generation later, he was always welcome in the place. High, sick, gone, lushed, or just plain scared, everybody still loved him. He’s been dead these many years, but I understand that a manuscript of his poetry still survives somewhere, and I wish some publisher would find it and take a look at it.”

“One night a skinny little boy came in with a whole mess of drums. For once we all realized we had a great artist. It was Dick Rough [Dave Tough], the first and greatest of the hipsters and one of the few really great musicians in the history of jazz. It turned out that he also wrote poetry no better or worse than my own, a precocious kid’s poetry. He and I became friends. In spite of the entire repertory of minor vices which were to become part of the jazz-man stereotype of a generation later, he was always welcome in the place. High, sick, gone, lushed, or just plain scared, everybody still loved him. He’s been dead these many years, but I understand that a manuscript of his poetry still survives somewhere, and I wish some publisher would find it and take a look at it.”

In the mid-twenties Dave came and went between the US and Europe with a clarinettist named Danny Polo who went on to play with Ambrose in London. They fetched up in places such as Nice, Ostend, Berlin and Paris playing small group jazz with banjoist cum guitarist George Carhart and clarinettist Mezz Mezzrow. Somewhere on one of these jaunts to Europe, it would appear that the Prince of Wales (later to become Edward VIII) actually sat in on Dave’s drums at a gig. Tough returned to the US in 1929 and moved to New York in 1935.

He was a very bright Bohemian who hated slang and felt everybody should speak the English language properly like him. He wouldn’t say: “Hey man what’s happening” and didn’t feel anybody else should either. He began to write for a music magazine called Metronome offering advice to drummers and once wrote an insightful piece about drummers and their choice of chewing gum!

The war came along and for a while he joined the US Navy and its big band with Artie Shaw until, like Shaw, he was invalided out. Like everyone else Artie was aware of Dave’s drinking and would have somebody police him so he didn’t fall off the bandstand. Every now and then he’d nod to him to take a solo and Dave would smile, shake his head and go on playing the relentless rhythm.

Evidently in time he became “a Dixielander who could also play Bop”, even though he confessed Bop wasn’t really his thing he admired Max Roach. In the mid-thirties he found himself playing big band music with Tommy Dorsey. Eventually he moved on to Jimmy Dorsey’s band although his best work is generally accepted as being with Woody Herman’s Herd in the forties. His powerfully playing made all the other drummers of the time sit up and take notice of his bass drum offbeats and his implied double-time rhythms within the main time signature.

Evidently in time he became “a Dixielander who could also play Bop”, even though he confessed Bop wasn’t really his thing he admired Max Roach. In the mid-thirties he found himself playing big band music with Tommy Dorsey. Eventually he moved on to Jimmy Dorsey’s band although his best work is generally accepted as being with Woody Herman’s Herd in the forties. His powerfully playing made all the other drummers of the time sit up and take notice of his bass drum offbeats and his implied double-time rhythms within the main time signature.

As far as equipment is concerned most photos show him with what is pretty much a standard drumset of the time. The difference is in how he tweaked it. He tuned his drums to definite pitches but insisted they produced a ‘wet’ sound which meant they played in their own register and didn’t interfere with the other instruments in the band. The advanced paradiddle book shows him behind a Slingerland set with single flange hoops, off set lugs, two mounted toms, a floor tom, what appears to be a 22” bass drum and a deep’ish snare set at an acute angle to accommodate his traditional grip.

Interestingly he kept a wet rag to wipe around his calf skin bass batter head to keep it damp and used a wooden beater. He wanted the flat wet sound this gave which didn’t conflict with the bass player’s note. He used larger than usual cymbals favouring the ‘Ride’ and  unusually often preferred to play brass accents on crashes alone without adding the usual snare or the bass to them. His set of Zildjian cymbals consisted of a pair of 13” hats, a couple of 15” crashes mounted on the bass drum, and a Chinese which he’d go to when he really wanted to add something to the last chorus and what I’m guessing was a 20” ride. There was nothing unusual about the cymbals themselves, but what he did to them certainly was. He cut chunks out of them to broaden their sound and removed strategic rivets to shorten it. He was famous for his ‘blurred’ ride figures where the sounds of strokes seemed to run into one another, this may well have come from his choice of heavy sticks with a round bead. There’s a photo of him in a dapper light-coloured double-breasted suit outside what I’m pretty sure was Zildjian’s shed hammering a cymbal on top of a tree trunk. Whether or not he’s ‘adapting’ a cymbal for himself is impossible to tell.

unusually often preferred to play brass accents on crashes alone without adding the usual snare or the bass to them. His set of Zildjian cymbals consisted of a pair of 13” hats, a couple of 15” crashes mounted on the bass drum, and a Chinese which he’d go to when he really wanted to add something to the last chorus and what I’m guessing was a 20” ride. There was nothing unusual about the cymbals themselves, but what he did to them certainly was. He cut chunks out of them to broaden their sound and removed strategic rivets to shorten it. He was famous for his ‘blurred’ ride figures where the sounds of strokes seemed to run into one another, this may well have come from his choice of heavy sticks with a round bead. There’s a photo of him in a dapper light-coloured double-breasted suit outside what I’m pretty sure was Zildjian’s shed hammering a cymbal on top of a tree trunk. Whether or not he’s ‘adapting’ a cymbal for himself is impossible to tell.

Dave Tough specialised in what he called organised time which was not metronomic. His philosophy was that human beings aren’t metronomes and drummers shouldn’t be either. If he felt the music demanded it he would lift the tempo a couple of bpm in a particular section and bring it back down again when the tune moved on. He evidently had a way of announcing his intentions to the rest of the band by playing five crotchets on the snare drum. He’d also do this if he felt they weren’t particularly on top of the piece.

If you’re looking for the essence of Dave Tough there’s lots on YouTube but check out his stuff with Woody Herman: ‘Four Men on a Horse’ and ‘Northwest Passage’ are really worth a listen.

Ed Shaughnessy remembered him as: “someone who didn’t have lightning-fast hands and never wanted to solo but was still one of the most in demand drummers in the history of jazz”.

Jim Chapin summed his playing up: “Some of the most revered players in history could hardly execute at all in the scholastic rudimental sense. What they did to an extraordinary degree was relate to the musical situation at hand, and to comment with their instruments in a unique and individual manner. This is a far more effective means of becoming indispensable than striving to be a drum athlete.”

Dizzie Gillespie added to this: “Dave never got in the way; he didn’t overplay. What we need today are a few more Dave Tough’s.”

Rexroth described him in print as “The first and greatest of the hipsters and one of the few really great musicians in the history of jazz.”

There is a bitter-sweet quote from Dave Dexter too which puts him into unhappy perspective: “ One of the two or three greatest drummers of all time, a sad guy, such a sad little guy”.

Dave Tough died after a fall on December 9th 1948.

Bob Henrit

June2014