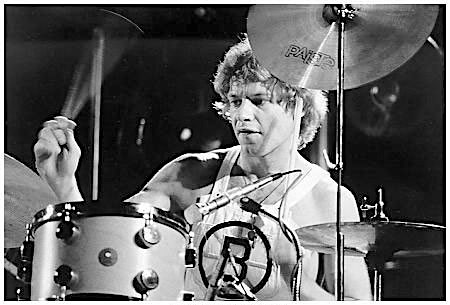

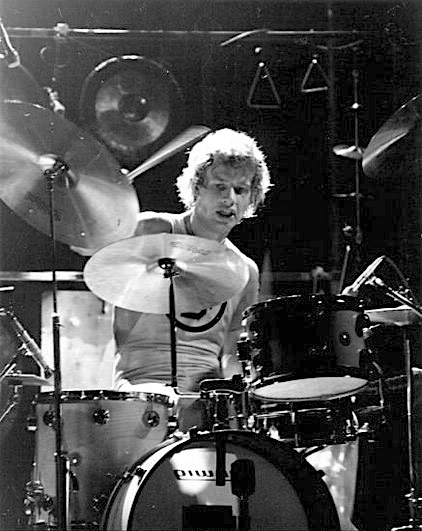

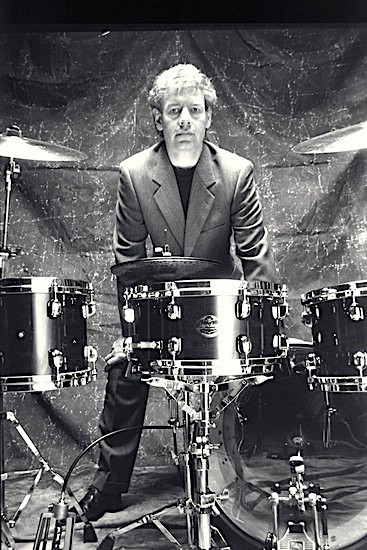

William Scott Bruford was born on May 17, 1949 and he and I were without doubt contemporaries. We’ve sat together talking about drums and drumming quite a few times over the years. Argent, Yes and several others were happily beating the same progressive rock path around the world so we were often thrust together at gigs, TV shows and festivals. I distinctly remember sitting at a table with him somewhere drinking coffee and playing 5 against 4, and 7 against 8 which was somehow important at the time.

William Scott Bruford was born on May 17, 1949 and he and I were without doubt contemporaries. We’ve sat together talking about drums and drumming quite a few times over the years. Argent, Yes and several others were happily beating the same progressive rock path around the world so we were often thrust together at gigs, TV shows and festivals. I distinctly remember sitting at a table with him somewhere drinking coffee and playing 5 against 4, and 7 against 8 which was somehow important at the time.

According to the internet Bill can, as of January 1st, 2009 be described as a retired English drummer, percussionist, songwriter, producer. I don’t think he’s given up completely and is still a record label owner. These days other than that, it seems his job description could simply say mentor and motivator.

Of course, he actually came to everybody’s attention as the original drummer of the progressive rock band ‘Yes’.

Along with other bands of the era, Yes were of course at the sharp end of progressive rock music for a period which ran from 1968 to 1972 and again from 1989 to 1992. After his departure from Yes the first time, Bruford spent the rest of the 1970s playing with King Crimson, touring with Genesis and UK, before forming his own band succinctly called Bruford. But there are more twists and turns to his career than this. Bill Bruford has been working at the very top end of progressive music for all his professional life.

Along with other bands of the era, Yes were of course at the sharp end of progressive rock music for a period which ran from 1968 to 1972 and again from 1989 to 1992. After his departure from Yes the first time, Bruford spent the rest of the 1970s playing with King Crimson, touring with Genesis and UK, before forming his own band succinctly called Bruford. But there are more twists and turns to his career than this. Bill Bruford has been working at the very top end of progressive music for all his professional life.

He returned to King Crimson for three years in the eighties before collaborating with various other artists such as The Roches, Patrick Moraz and David Torn, before forming his own jazz band called Earthworks in 1986. He then played in Anderson, Bruford, Wakeman, Howe, which eventually led to his second stint in Yes.

Bruford played in King Crimson for his third and final tenure between 1994 and 1997, after which he continued with Earthworks and further collaborations. So it really is fair to say he’s been around.

But as I intimated, Bill Bruford surprised everybody by retiring from public performance on the very first day of 2009. But he released ‘Bill Bruford: The autobiography, on February 1st, 2009 and continues to speak and write about music as well as operating his two record labels: Summerfold and Winterfold. But there’s more – in 2016, after four-and-a-half years of study, Bruford deservedly earned himself a PhD in Music at the University of Surrey. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Yes a year later.

But to begin at the beginning, as we like to do in ‘Groovers and Shakers’, Bill Bruford was born in Sevenoaks, a market town in Kent, which was also the home of John Donne famous for his poem “No man is an island” and HG Wells who wrote “War of the worlds”. He was the third of Betty and John Bruford’s children, His father was a local veterinary surgeon and he has a brother, John, and a sister, Jane. At thirteen he was a ‘boarder’ at the prestigious Tonbridge School when he decided to take up drumming after watching American jazz drummers on a BBC TV series called ‘Jazz 625’ in 1964 (named after the increased number of horizontal lines the BBC were transmitting with for improved definition) and practiced in the loft of his house. This was the start of a lifelong interest in that genre of music. He says that Max Roach, Joe Morello, Art Blakey and Ginger Baker were the most influential drummers to him in his early days.

But to begin at the beginning, as we like to do in ‘Groovers and Shakers’, Bill Bruford was born in Sevenoaks, a market town in Kent, which was also the home of John Donne famous for his poem “No man is an island” and HG Wells who wrote “War of the worlds”. He was the third of Betty and John Bruford’s children, His father was a local veterinary surgeon and he has a brother, John, and a sister, Jane. At thirteen he was a ‘boarder’ at the prestigious Tonbridge School when he decided to take up drumming after watching American jazz drummers on a BBC TV series called ‘Jazz 625’ in 1964 (named after the increased number of horizontal lines the BBC were transmitting with for improved definition) and practiced in the loft of his house. This was the start of a lifelong interest in that genre of music. He says that Max Roach, Joe Morello, Art Blakey and Ginger Baker were the most influential drummers to him in his early days.

His start on the drums came after his sister bought him a pair of wire brushes as a birthday present and in place of the drums he hadn’t yet acquired, Bill would practice with them on album sleeves after somebody suggested to him they sounded like a snare drum! Like just about everybody I’ve written about he started his drumming career with a snare drum before later graduating to a proper one up, one down, 4-piece Olympic kit. Sometime later took a few lessons from a guy called Lou Pocock, who played with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.

During his time at boarding school, Bill was friends with several guys who were also jazz fans, one of them turned out to also be a drummer who gave Bruford lessons and Bill says he actually taught him how to improvise using a tutor book by American jazz drummer and Moeller Method practitioner Jim Chapin. These guys from school then performed as a four-piece named The Breed who were a rhythm and blues and soul band which Bruford played with from 1966 to 1967. He stayed until he couldn’t make all their gigs which meant of course they had to find another drummer.

During his time at boarding school, Bill was friends with several guys who were also jazz fans, one of them turned out to also be a drummer who gave Bruford lessons and Bill says he actually taught him how to improvise using a tutor book by American jazz drummer and Moeller Method practitioner Jim Chapin. These guys from school then performed as a four-piece named The Breed who were a rhythm and blues and soul band which Bruford played with from 1966 to 1967. He stayed until he couldn’t make all their gigs which meant of course they had to find another drummer.

After he left boarding school, Bruford took a gap year off before he planned to start an economics course at Leeds University, this would have begun in September 1968 when I was slightly surprised to learn he auditioned for Savoy Brown (who were actually an ‘out and out’ British Blues Band) in a pub in Battersea. He wasn’t given the gig. However, he hung around until the auditions were over and evidently having told them they’d hired the wrong guy he was able to talk his way into the band. His tenure with them lasted three gigs as they felt he evidently “messed with the beat”. Next, he joined a psychedelic rock band called ‘Paper Blitz Tissue’ for a very short time.

Meanwhile he saw an advert in a music shop which had been put there by a group somewhat pessimistically called The Noise! They were looking for a drummer to play with them for a six-week residency at the Piper Club in Rome. He did the gig and remembers the experience as being “ghastly”, because to his mind his bandmates could not play properly, He left them suddenly in Italy and was forced to hitchhike all the way back to London – with his drums. There’s definitely a lesson to be learned here – don’t leave any band until you get home safely with your gear! (BTW this set he struggled home with might well have been the Ludwig one he eventually sold to print mogul Rick Desmond and immediately regretted the transaction and tried to get back. You can read about it in a Dolbear piece on Mr. Desmond from several years ago called “Something else for the weekend”.)

Following that laborious and uncomfortable return to London the by now nineteen-year old Bruford settled into a flat in North London and placed an advertisement for work as a drummer in what at the time was the Musician’s bible: the Melody Maker. Jon Anderson, who was in a band called ‘Mabel Greer’s Toyshop’ at the time saw it. They were based in London and were a psychedelic rock band which had bassist Chris Squire and a guitarist named Clive Bayle. These guys were looking for someone to replace their drummer who was leaving. The first time they all met was in June 1968 when Anderson was so impressed with Bruford, he invited him to play with the band that very evening at a college in Deptford. At the time it seems their whole set consisted of their version of Wilson Pickett’s “Midnight Hour”. This was the only song they knew how to play. We’re told Bruford was impressed by the band’s ability to sing in harmony!

Following that gig, Bruford had several offers to join soul bands, one of which was evidently paying as much as £30 a week! (That exclamation mark was not derogatory because while that wasn’t great money at the time unfortunately it was the going rate for casual gigs.) However in the end he chose to form a new group with Anderson and Squire. They got down to rehearsals, which ended in Peter Banks taking the place of Bayley on guitar. They changed their name to Yes and brought in Tony Kaye on keyboards. They were all confined to the same house in London in case they got a gig somewhere and needed to move quickly and Bill Bruford described those early days as being like a fireman – waiting for the bell to ring before sliding down a greasy pole and getting off to a gig somewhere. It seems there was a certain amount of friction in Yes brought on by the various differences to do with the diverse backgrounds of its members. Bill Bruford says he was unable to understand Jon Anderson’s Lancashire accent.

Following that gig, Bruford had several offers to join soul bands, one of which was evidently paying as much as £30 a week! (That exclamation mark was not derogatory because while that wasn’t great money at the time unfortunately it was the going rate for casual gigs.) However in the end he chose to form a new group with Anderson and Squire. They got down to rehearsals, which ended in Peter Banks taking the place of Bayley on guitar. They changed their name to Yes and brought in Tony Kaye on keyboards. They were all confined to the same house in London in case they got a gig somewhere and needed to move quickly and Bill Bruford described those early days as being like a fireman – waiting for the bell to ring before sliding down a greasy pole and getting off to a gig somewhere. It seems there was a certain amount of friction in Yes brought on by the various differences to do with the diverse backgrounds of its members. Bill Bruford says he was unable to understand Jon Anderson’s Lancashire accent.

During his first stint with the band, Bill played on their first five studio albums: Yes, Time and a Word, The Yes Album, Fragile and Close to the Edge. He also wisely started to write songs and his first attempt at composition was “Five Per Cent for Nothing”, which was a track on Fragile.

The internet will tell you that the band were no strangers to alcohol, but to be frank in those halcyon days it would be difficult to find a band who didn’t fit somewhere into that description! Bruford evidently doesn’t remember a lot of “sex, drugs and rock n’ roll” although frankly it didn’t help them to avoid those particular temptations when their manager, Roy Flynn owned The Speakeasy which was the premier watering hole for bands and celebrities of the era. He would insist the place would stay open until the band got there. This meant Yes, or any other thirsty band could play a gig in the midlands or anywhere within a hundred-and-fifty-mile radius of London and still make it back to the ‘Speak’ by about two o’clock, whereupon they would drink an elegant sufficiency of Whisky (or possibly whiskey) and Coca-Cola.

Bruford says Yes were hot-blooded and argumentative (we’re told sometimes this resulted in fisticuffs) with personality conflicts being the eventual reason for his exit from the band. There were differences in social backgrounds, and other issues that set the members of the band in a constant state of friction.

By 1972, he felt that Yes had come as far as it could, or at least inasmuch as far as he could contribute anything to it. He didn’t want to spend what he felt was an inordinate amount of time in the studio debating chords and producing records that he felt would only be in the shadow of Close to The Edge. But it seems his main reason for leaving the band was the fact that his rehearsals with bassist Chris Squire were always delayed. Waiting for him to turn up was the worst thing he had to endure although he once had a fist-fight with him after a concert, because they had violently disagreed about who had played badly.

By 1972, he felt that Yes had come as far as it could, or at least inasmuch as far as he could contribute anything to it. He didn’t want to spend what he felt was an inordinate amount of time in the studio debating chords and producing records that he felt would only be in the shadow of Close to The Edge. But it seems his main reason for leaving the band was the fact that his rehearsals with bassist Chris Squire were always delayed. Waiting for him to turn up was the worst thing he had to endure although he once had a fist-fight with him after a concert, because they had violently disagreed about who had played badly.

So, he left Yes to join King Crimson. He’s on record commenting: “In Yes, there was an endless debate about ‘should it be F natural in the bass with G sharp on top by the organ, or should it be the other way around?’. In King Crimson, it seems this was not an issue … you were just supposed to know”. Rehearsals began in September 1972, followed by an extensive UK tour. Bruford had a great memory for complicated drum parts like the long percussion and guitar part in the middle of “20th Century Schizoid Man, he accomplished it “by listening to it and just learning it.”

Bruford is of the opinion that the six months that percussionist Jamie Muir was in the group were highly influential on him as a player. Larks’ Tongues in Aspic was released early the next year, and the group spent the end of 1973 touring Britain, Europe, and America. Bruford played on Starless and Bible Black and Red before Robert Fripp disbanded King Crimson in September 1974 although Bill is on their live album, USA which came out in 1975.

Following his departure Bill Bruford said in an interview he felt his “sense of direction was rather stymied” and was unsure on what to do next. Rather than get involved with the next project straight away, he chose to wait for an offer which appealed to him more. In 1975 he played drums on Squire’s solo album Fish Out of Water. Bruford also joined National Health for a few live performances. He wisely decided against their full-time offer to join them, feeling there were already enough writers in the group, and felt his contributions to the music, much of which was already written, may have caused problems

In 1976, Bruford spent six months with Genesis as their live drummer on their North America tour which also went to Europe. This was the first tour after Peter Gabriel left and Phil Collins took over on lead vocals on their first album without him called A Trick of the Tail. Bruford and Collins had known one another for several years and had performed together with Collins’ side project Brand X. Interestingly the internet tells me Roger Taylor was offered the Genesis gig and turned it down – this was just a year before “We will rock you” was released so history would appear to show he made the right decision!

In 1976, Bruford spent six months with Genesis as their live drummer on their North America tour which also went to Europe. This was the first tour after Peter Gabriel left and Phil Collins took over on lead vocals on their first album without him called A Trick of the Tail. Bruford and Collins had known one another for several years and had performed together with Collins’ side project Brand X. Interestingly the internet tells me Roger Taylor was offered the Genesis gig and turned it down – this was just a year before “We will rock you” was released so history would appear to show he made the right decision!

Moving on, in 1977, he formed his own band named Bruford with Dave Stewart on keyboards, Jeff Berlin on bass, and Allan Holdsworth on guitar.

The first album was called Feels Good To Me and was released in 1978 and was recorded as a solo project. The next album was a mainly instrumental offering with some spoken words called One Of A Kind in 1979.

Not one but two live albums came out of this period. Bruford – Rock Goes to College is a 2006 DVD release from the BBC Television series and The Bruford Tapes (1979), compiled from live shows at a well-known progressive gig we all played at called My Father’s Place in Roslyn, Long Island. Following his first solo album, he was reunited with King Crimson’s John Wetton in another progressive rock group called U.K.. During his time in the band, from 1977 to 1978, the band released its debut album called U.K. (1978) and conducted one U.K. tour and a couple of North American tours. After this he was dismissed from the band, due to his disagreement with Wetton, and keyboardist Eddie Jobson’s decision to fire guitarist Allan Holdsworth, whom he’d brought into the band. Subsequently he turned his focus on his own band, Bruford.

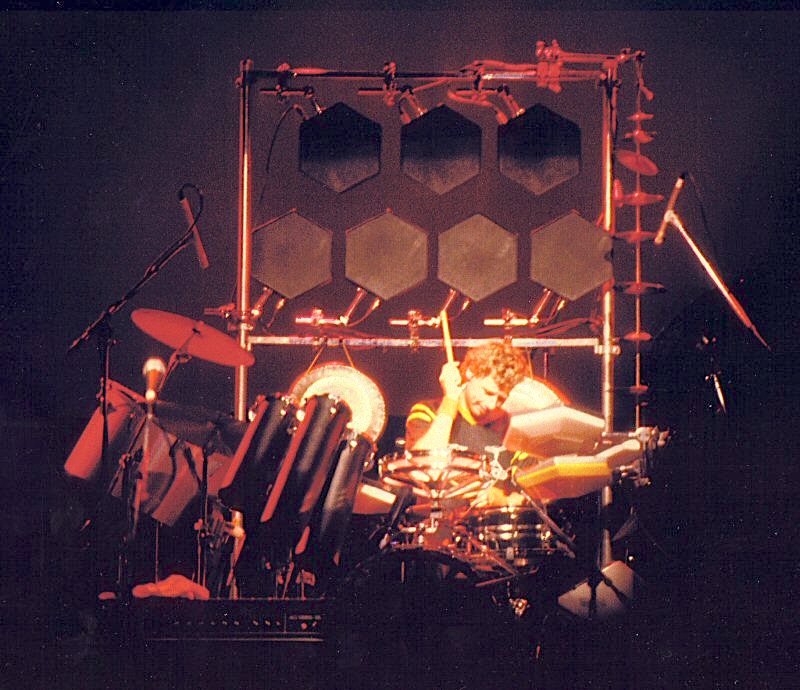

He became part of another formation of King Crimson again in 1981 with a different line-up. This one had Bruford, Robert Fripp, Tony Levin and Adrian Belew. They recorded Discipline (1981), Beat (1982), and Three of a Perfect Pair (1984) with them, moving to a kit of both acoustic and electronic drums and using his renowned polyrhythmic style, before they disbanded again in 1984.

He became part of another formation of King Crimson again in 1981 with a different line-up. This one had Bruford, Robert Fripp, Tony Levin and Adrian Belew. They recorded Discipline (1981), Beat (1982), and Three of a Perfect Pair (1984) with them, moving to a kit of both acoustic and electronic drums and using his renowned polyrhythmic style, before they disbanded again in 1984.

Bill was famous for his involvement with electronics In the early 1980s but it seems he felt that electronic drum technology wasn’t able to reproduce the sounds he wanted so he “decided to wait until it got a bit better”. He then teamed up with Swiss keyboardist Patrick Moraz, a former member of Yes in the 1970s who unbeknown to Bill lived a few minutes away from his home in Surrey. As Moraz/Bruford, they released Music For Piano and Drums in 1983 and Flags in 1985. Both albums were recorded on acoustic instruments. They did some shows to support these albums including a Japanese tour.

In 1986, Bruford formed his own jazz group Earthworks with Django Bates,, Iain Ballamy, Mick Hutton on bass, and Dave Stewart. By then, electronic drum technology had improved to Bill’s satisfaction and he resumed using the instrument, specifically the electronic Simmons kit The band though came back in the 1990s with an acoustic line-up and in the later years of his career he returned to using a primarily acoustic drum set. In 1990, he was inducted into the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame.

There was another twist Anderson, Bruford, Wakeman, Howe (referred to by the acronym ABWH). It was composed of those former members of Yes with the addition of Tony Levin.

Bruford would re-join Yes briefly in 1991 and 1992 for the Union album and tour, so titled because it brought together ABWH and the members of Yes prior to the union as an eight-member band. He had this to say of the album:

“Well, the more money you pay for a record, the more you interfere with it – and this was a big budget record. So, they eventually decided that the guys in France (Anderson, Bruford, Wakeman and Howe) needed the assistance of all the other Yes guys in California (Chris Squire, Tony Kaye, Trevor Rabin and Alan White). So, our work was duly e-mailed, I guess, to them. They were then put on and found lacking. Then, what was also put on was a cast of a thousand studio musicians. So, the whole thing turned into the most God awful, auto-corrected mess you could possibly imagine! The worst record I’ve ever been on.”

However, he had something more supportive to say of the tour:

“It was just a sort of a summer vacation. It was fun to do in the sense there were some ‘old pals’ and it was possible to do because we didn’t have to give rise to any new music. So, in as much as the band was just playing repertoire material, there was kind of a ‘ticket buy’ in the idea of all those, you know, the entire cast of Dallas on stage at once, kind of thing. And there was some kind of attraction to that. But that was really all it was, I think. And I think I was probably an unnecessary spare part. So I didn’t enjoy it terribly. But those gigs can be quite fun as performing in huge stadiums can be quite fun on a kind of purely visceral level. Just kind of being there and enjoying it. I don’t venture; however, you’d want to give up your day job to do it.”

“It was just a sort of a summer vacation. It was fun to do in the sense there were some ‘old pals’ and it was possible to do because we didn’t have to give rise to any new music. So, in as much as the band was just playing repertoire material, there was kind of a ‘ticket buy’ in the idea of all those, you know, the entire cast of Dallas on stage at once, kind of thing. And there was some kind of attraction to that. But that was really all it was, I think. And I think I was probably an unnecessary spare part. So I didn’t enjoy it terribly. But those gigs can be quite fun as performing in huge stadiums can be quite fun on a kind of purely visceral level. Just kind of being there and enjoying it. I don’t venture; however, you’d want to give up your day job to do it.”

Bill Bruford and Steve Howe would later undertake a recording project together in 1992/1993 to use an orchestra to reinterpret some of Yes’ works. The resulting album, titled Symphonic Music of Yes was released on RCA records in 1993.

King Crimson re-emerged once more in 1994 as a six-piece band, consisting of its 1980s line-up along with Trey Gunn, Pat Mastelotto sharing the drumming duties with Bruford. It was called the “double trio” configuration and between 1994 and 1996 they prolifically they released the EP Vrooom (1994), the full-length studio album Thrak (1995), and two live albums, B’Boom: Live in Argentina (1995) and Thrakattak (1996).

Rehearsals to create new King Crimson material followed, as well as a week of performance with what was called the sub-group ProjeKcts One in 1997, after which Bruford left the band and its iterations (what a great word which means doing things over and over again as in reiterate ) for good. His reason for moving on from King Crimson was his frustration with rehearsals, which he felt weren’t going anywhere.

He was rapidly losing interest in electronics and he moved his focus back to acoustic jazz, firstly in a collaboration with Americans Eddie Gomez and Ralph Towner (1997) and then with an all-new acoustic Earthworks (1999-2008). While this was still his primary focus, he also went looking for other people to collaborate with in what would turn out to be the culmination of his long career. This, included a jazz-rock band Bruford Levin Upper Extremities (1998), a duo with Dutch pianist Michiel Borstlap (2002-2007), the contemporary composer Colin Riley with the Piano Circus Collective in 2009, and of course in presenting drum clinics.

He was rapidly losing interest in electronics and he moved his focus back to acoustic jazz, firstly in a collaboration with Americans Eddie Gomez and Ralph Towner (1997) and then with an all-new acoustic Earthworks (1999-2008). While this was still his primary focus, he also went looking for other people to collaborate with in what would turn out to be the culmination of his long career. This, included a jazz-rock band Bruford Levin Upper Extremities (1998), a duo with Dutch pianist Michiel Borstlap (2002-2007), the contemporary composer Colin Riley with the Piano Circus Collective in 2009, and of course in presenting drum clinics.

It hasn’t all been plain sailing for Bill Bruford who has been involved in a number of abortive projects. One in 1976 was a trio with Rick Wakeman and John Wetton which Bruford talks about as “an abortive and late rehearsal/audition with bass player Jack Bruce out at his mansion in Essex but nothing came of that.” He was also approached in 1985 by Jimmy Page to be the drummer for The Firm his new band with Paul Rodgers and Pino Palladino. “We rehearsed briefly” he said, “but I think we decided we were mutually unsuited”. There was another ‘Supergroup’ with Keith Emerson and Greg Lake (of ELP), with Rick Wakeman and John Wetton (to have been called British Bulldog if it had happened

Bruford retired from performance (except for one performance with Ann Bailey’s Soul House in 2011. He retired from studio recording at the same time, although his final studio work, Skin & Wire was not released until later that year. His autobiography was released in early 2009. As I said, In 2016, after four years of study, Bruford was a awarded a PhD in Music at the University of Surrey so these days we should call him Dr.Bruford or perhaps more accurately Professor Bruford..

There’s a long list of drummers who have been cited as having Bruford as a major influence including Danny Carey, Tim Alexander, Mike Portnoy, Brann Dailor, Matt Cameron, Chris Pennie and a great many more.

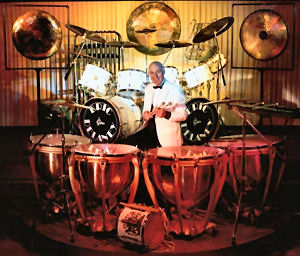

As far as drums are concerned Bill’s been around. As I said he started with Olympic and moved onto a Ludwig set with some sort of chrome finish and a 400-snare drum. Next came a natural Hayman again with the 400 and a Hayman wood-shell snare. Then in 1972 came the natural Ludwig which he mixed with various Hayman drums and a 6.5” deep Ludwig Super-Sensitive to make a hybrid set. By 1972 he’d moved on to the hybrid Ludwig/Hayman set with a Premier timbale. And five years later it seems he was using the same kit.

As far as drums are concerned Bill’s been around. As I said he started with Olympic and moved onto a Ludwig set with some sort of chrome finish and a 400-snare drum. Next came a natural Hayman again with the 400 and a Hayman wood-shell snare. Then in 1972 came the natural Ludwig which he mixed with various Hayman drums and a 6.5” deep Ludwig Super-Sensitive to make a hybrid set. By 1972 he’d moved on to the hybrid Ludwig/Hayman set with a Premier timbale. And five years later it seems he was using the same kit.

Most of his kits were pretty standard sizes 12 x 8”, 13 x 9”, 14 x 14”, 16 x 16”, 22 x 14” and apart from adding Rototoms in ‘77 stayed that way until he moved on to Tama in ‘81 and started playing birch shelled Superstars with Tama steel snares and of course a 22” ‘gong’ drum. This was when things got interesting with smaller toms, woodblocks, triangles, toy cymbals, cowbells and metal plates, 14”, 16” and 24” gongs, low Octobans and Simmons SDSV for that very distinctive Bruford sound,

In 1987 he changed the now out of date Simmons for the all singing, all dancing SDX which had just come out in the January in time for the NAMM and Frankfurt music shows. By 1992 he’d transferred his allegiance to Artstar II, and a couple of years later Tama Starclassic arrived in Canary yellow. In 2001 his Signature snare drum was released and two years later it was all over for him as far as playing was concerned.

As far as cymbals are concerned, he’s played: Paiste, Zildjian and Zyn – often all at the same time. His Paistes were a mixture of Formula 602, 2002, Signature, Sound Creation and China. With Zildjian there’s no discernible pattern, he seems to have used Avedis or whatever took his fancy.

If you want to delve further into the legend of Dr Bruford, I suggest you go on line and there’s some interesting stuff particularly including something from The Drummer’s Journal written by Tom Hoare and Iain Bellamy.

Bill’s been prolific and correspondingly this Groovers piece has taken a lot of researching. I’ve done my best to look into it thoroughly but if there are any problems with the piece, I’ll use the following abbreviation I once used as a get-out on drum catalogues and price lists i was working on in a previous life…

Bill’s been prolific and correspondingly this Groovers piece has taken a lot of researching. I’ve done my best to look into it thoroughly but if there are any problems with the piece, I’ll use the following abbreviation I once used as a get-out on drum catalogues and price lists i was working on in a previous life…

E&OE!

Bob Henrit

December 2018