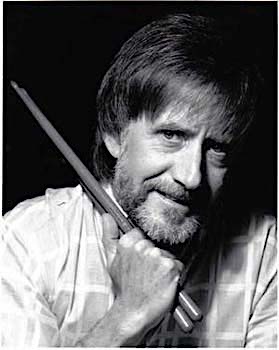

As it happens I owe a great deal to this month’s subject, Dougie Wright, as it was he who inadvertently got me my start in big time music. He had been playing drums for ‘The John Barry 7’ who backed a very popular ‘pop star’ and I received the call to play with him. This was after that particular star’s indomitable manager put two and two together and decided she could get away with a 4-piece band and save almost 50% of the wages bill.

As it happens I owe a great deal to this month’s subject, Dougie Wright, as it was he who inadvertently got me my start in big time music. He had been playing drums for ‘The John Barry 7’ who backed a very popular ‘pop star’ and I received the call to play with him. This was after that particular star’s indomitable manager put two and two together and decided she could get away with a 4-piece band and save almost 50% of the wages bill.

Fortunately for me, Dougie was no longer knocked out by being on the road and ultimately wanted to try his hand at being a session player, and record in a nice warm studio during the day, and get home to his own bed every night. So the gig which was up for grabs was with Adam Faith and I grabbed it – with both hands. The rest is history as far as I’m concerned, and I thanked him profusely 56 years later when we bumped elbows at the 2018 UK National Drum Fair.

Dougie Wright was born on January 10th, 1937 and became an in-demand drummer during the British ‘beat boom’ of the 1960’s. As is the nature of these things, it was his work with the Bill Marsden Big Band in Leeds which brought him into contact with the band’s sax-player Jimmy Stead. Jimmy joined the John Barry Seven in 1958 and recommended Dougie as a successor to the group’s original drummer, Ken Golder. Some time later a guitarist called Vic Flick joined the group, who soon after invented the James Bond guitar riff (for which he was paid the usual session rate which was around £7).

Dougie Wright lasted with the John Barry Seven until October, 1962, (doing performances such as playing in top hat and tails at a Royal Command Performance with Adam Faith) and in the fullness of time Andy White joined the band, who of course (I hope you know) played on The Beatles tune “Love Me Do”.

Dougie Wright lasted with the John Barry Seven until October, 1962, (doing performances such as playing in top hat and tails at a Royal Command Performance with Adam Faith) and in the fullness of time Andy White joined the band, who of course (I hope you know) played on The Beatles tune “Love Me Do”.

Next Dougie threw his lot in with the Ted Taylor Four and started playing in London’s night clubs like The Jack of Clubs in Brewer Street, often until 3am every morning. However, a session ‘fixer’ offered him a way to possibly get more sleep by becoming a session drummer and doing up to five sessions a day.

But jazz was his first love and by the seventies he was back playing it full-time. This was first with the Eddie Thompson Trio and later with the Harry Stoneham Band on the Michael Parkinson Show. As of the 1990’s, he was living in Leicester and teaching music at the college there.

The list of artists he worked with and whose records he played on is breathtakingly impressive – Cilla Black (he played on ‘Step Inside Love’), Jeff Beck (‘Hi Ho Silver Lining’), Herman’s Hermits (‘No Milk Today’), David Bowie (‘Rubber Band’), Paul McCartney (‘Uncle Albert’), the Bay City Rollers (‘Bye Bye Baby’), Marianne Faithfull (‘Come And Stay With Me’), Matt Monro (‘Gonna Change The World’), Alvin Stardust (‘My Coo Ca Choo’), Tom Jones (‘Not Responsible’), Van Morrison (‘Here Comes The Night’ and ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’) – and possibly something which was not his favourite work: The Wurzels’ hit “I’ve Got A Brand New Combine Harvester”.

Actually these are the tip of the iceberg and there are many more, including 11 major hits with Adam Faith before we Roulettes started recording with him. He also played drums on Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin’s at the time controversial number one: “Je T’aime, Moi Non Plus”. This is just a selection and his website has even more songs and artists on it. He did the music for ‘Juke Box Jury’ but one song whose success I know he’s proud of was number one on both sides of the Atlantic. That was “World Without Love” by Peter and Gordon. Otherwise here’s a partial list of those which still get regularly played on the radio:

Actually these are the tip of the iceberg and there are many more, including 11 major hits with Adam Faith before we Roulettes started recording with him. He also played drums on Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin’s at the time controversial number one: “Je T’aime, Moi Non Plus”. This is just a selection and his website has even more songs and artists on it. He did the music for ‘Juke Box Jury’ but one song whose success I know he’s proud of was number one on both sides of the Atlantic. That was “World Without Love” by Peter and Gordon. Otherwise here’s a partial list of those which still get regularly played on the radio:

‘What Do You Want’, ‘Someone Else’s Baby’, ‘Made You’, ‘Lonely Pup’, ‘Eloise’, ‘Yesterday Man’, ‘Out Of Time’, ‘Lovers Of The World Unite’, ‘Love Grows’, ‘You’ve Got Your Troubles’, ‘Here It Comes Again’, ‘Good News Week’, ‘Little Arrows’, ‘I’ve Been A Bad Bad Boy’, ‘Gimme Dat Ding’, ‘Long Long Live Love’, ‘Message Understood’, ‘I Love To Love’, ‘Here Comes The Night’, ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’, ‘Edelweiss’, ‘The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore’, ‘My Ship Is Coming In’, and lot, lots more.

Despite the success of all of these records, Dougie, like every other session player of his ilk, never saw a penny in royalties.That’s because it’s not the way it was done then or now. As a session player you always got paid whether the record was successful or otherwise. How it works is that a fixer calls you to do a session and you’d turn up with your drums and get yourself set-up in time for what was called the first down-beat. At the end of the session (if it didn’t run into overtime) you’d be presented by the fixer (who had arrived just in time to do this) with a brown envelope containing the dosh (Dougie clams this would be £7 but I distinctly remember getting £5/15/6 for a million selling record called “Concrete And Clay” in 1964).

I saw an interview with Dougie where he was asked about royalties and he evidently laughed. “Oh I wish! We didn’t get any of that – we were paid according to the Musicians’ Union scale. During the ’60s, for a three-hour studio session I’d take home £7, but for a two-hour session it was five guineas.

I saw an interview with Dougie where he was asked about royalties and he evidently laughed. “Oh I wish! We didn’t get any of that – we were paid according to the Musicians’ Union scale. During the ’60s, for a three-hour studio session I’d take home £7, but for a two-hour session it was five guineas.

“But don’t get me wrong: that was alright in those days. And then on top you had five shillings porterage, which was petrol money for you to get your drum kit to the studio.GETTY

“But it was a wonderful time. I’d be playing three, four, five sessions a day sometimes. Not just pop songs – I’d do jingles for TV, film scores, radio broadcasts, whatever came along.

“You got the call, you put it in the book and you made sure you were there on time. And if you were punctual and professional and compatible with all the other guys, you got more work”. However as anyone working in the sixties will tell you, studio session work was not a licence to print money, and you certainly couldn’t expect to make a fortune doing it.

As I said, in those days work came through “fixers”, who were employed at all the studios across London to provide musicians for recording sessions – including Abbey Road, Decca, Pye, Fontana and many others. Dougie would receive a phone call from a chap called Charlie Katz (who everybody wanted to make their best friend). Charlie would ask him if he was free and could turn up for a session at a certain time? He’d pack up his drums and set off. If Dougie couldn’t make it, the fixer would go to the next name on his list of capable drummers and call him. (This was why drummers then didn’t want to be on the road in case they missed out on a bunch of sessions. This happens/happened in Nashville too where producers didn’t want you to go away even for a weekend of fun gigs in case a track you’d just played on needed amending. Drummers were desperate to play live and keep their chops up, but didn’t dare leave.)

As Dougie says:“The important thing was always to remember that you weren’t there to make a name for yourself,” he says. “You were there to make a name for the artiste. Whoever that would be? I rarely knew who I would be backing until I got to the studio.”

As Dougie says:“The important thing was always to remember that you weren’t there to make a name for yourself,” he says. “You were there to make a name for the artiste. Whoever that would be? I rarely knew who I would be backing until I got to the studio.”

“The stars were all friendly,” he remembers. “We were all there to do a job together, getting on with it the best we could. There were no prima donnas and you couldn’t afford to have your head in the clouds or be star-struck. It really was a case of ‘you’re there to do a job, and you won’t get paid until you do it… and if you don’t do it well, you won’t get asked again’.”

“When we were in the studios together we were all equal, but not so much afterwards,” says Dougie.

“The session guys would go out together…. There was a very strong sense of community among us – the rhythm section players especially were like a band of brothers. We all knew each other socially and professionally – and we knew each other’s’ abilities too. There were certain players – I won’t name names – who went on to great things but who couldn’t hack it as studio players. They were soloists, they couldn’t make a rhythm section tick.”

Among Dougie’s contemporaries who made the leap from session player to stars in their own right were keyboard players Reg Dwight (later Elton John) and Rick Wakeman with whom he played on the Edison Lighthouse hit “Love Grows”. He also did sessions with the nucleus of the band that would become Led Zeppelin.

“Lovely lads,” says Dougie, “I worked with John Paul Jones from Led Zeppelin a fair bit. We used to do ‘Ready Steady Go’ together – I was the regular drummer on that show for a couple years around 1965 [once its music went live and nobody mimed any more] and John often deputised on the bass. And then I used to do sessions with Jimmy Page too. I’ve still got his signature on a contract somewhere, right next to mine.”

Also while doing ‘Ready, Steady, Go’, he remembers playing for Diana Ross and the Supremes when they performed on the show. As he remembers it, The Divine Miss Ross was exceedingly impressed when she heard them play.

Also while doing ‘Ready, Steady, Go’, he remembers playing for Diana Ross and the Supremes when they performed on the show. As he remembers it, The Divine Miss Ross was exceedingly impressed when she heard them play.

Dougie played left-handed and maintains it wasn’t that which defined him. No, the secret of his playing was that he adapted his jazz thinking to pop drumming.

His heroes turn out to be every drummer he ever saw because early on he realised that we all had something to offer one another. However, like all drummers of his era, of course he was influenced by Buddy Rich and the bands of Kenton, Brubeck, Mulligan, The Modern Jazz Quartet, Ellington, Basie and countless others.

It was at his mother’s suggestion that he took piano lessons, something he did for a couple of years. But the die was cast and he was inextricably drawn to the drums. He’d left school and had his first job and decided to take lessons to play them properly. The main music shop in Leeds in those days was Kitchens and he was evidently told to turn up there with a pair of sticks and his Buddy Rich tutor book and set about learning to play. He learned to read music which stood him in really good stead from the recording sessions point of view. He maintained then as now, it’s a very important thing to be able to do, and I’m told the inability to do this holds many drummers from the sixties back.

It was at his mother’s suggestion that he took piano lessons, something he did for a couple of years. But the die was cast and he was inextricably drawn to the drums. He’d left school and had his first job and decided to take lessons to play them properly. The main music shop in Leeds in those days was Kitchens and he was evidently told to turn up there with a pair of sticks and his Buddy Rich tutor book and set about learning to play. He learned to read music which stood him in really good stead from the recording sessions point of view. He maintained then as now, it’s a very important thing to be able to do, and I’m told the inability to do this holds many drummers from the sixties back.

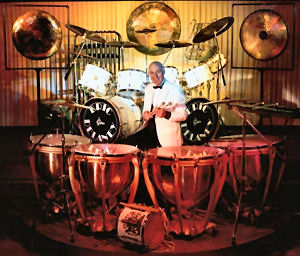

As far as a collector of drums he doesn’t appear to be one! His very first drum would appear to have been built in 1924 and was a Hawkes. I’ve looked around the world wide web and found him with a Premier kit and I think an Ajax. I would have thought that because of the high-profile work he was doing that, like many of the rest of us, he would have been issued with a Trixon kit by Ivor Arbiter. But I spoke to Dougie who told me he’d never been invited to endorse anything. He informed me he once had a Trixon snare and still has a ‘64 Gretsch set that he uses, and in the past he had a Camco which he sold to a collector in the Midlands which seems to have found its way back to America.

As I said, he never endorsed any particular drums although he’s stuck with Zildjian cymbals (with the odd Sabian mixed in) for many years.

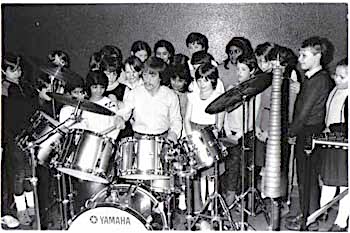

Today Dougie makes part of his living (at 82!) by teaching drumming at his home in Leicestershire, a job he took in 1977 when the emergence of punk and new wave meant the demand for dedicated session musicians pretty much disappeared. I calculate he’s been playing professionally for 64 years.

Today Dougie makes part of his living (at 82!) by teaching drumming at his home in Leicestershire, a job he took in 1977 when the emergence of punk and new wave meant the demand for dedicated session musicians pretty much disappeared. I calculate he’s been playing professionally for 64 years.

London was without a doubt the centre of the musical and cultural revolutions and Dougie found himself very much part of it. He played on 15 number ones and has evidence in his collection of work diaries to prove he played on 4200 sessions. If we assume they were all three hour sessions which was the norm for a session with A and B sides to be recorded, with the aid of a calculator you can ascertain he sat on a drum stool for 12,600 hours. Or if you prefer almost 19 months. These figures mean he also played on at least 8400 music tracks – not counting films, TV and radio. He confesses that the happy memories are tinged with a certain amount of frustration. With such a prodigious output in such a short a time, trying to prove – or even remember – his part in every song he played on is hard.

These days, as I said he teaches and still plays drums but he’s also a singer. And believe it or not, he actually raps, although possibly without the excessive use of the ‘F – word’.

Bob Henrit

May 2019