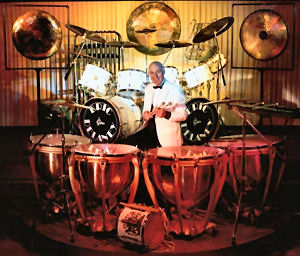

(Editors note – Try as we might, none of us could find ANY photos of Frank Ippolito or the Professional Percussion store. If you happen to have one and would allow us to put it into this article, please get in contact)

I struck up a rather special friendship in the very late sixties with Frank Ippolito, and after deliberating about including him in Groovers & Shakers, I decided he was very much of the same stamp as Ivor Arbiter. In short he was America’s equivalent of Ivor and an Anglophile to boot, for reasons I’ll explain in a moment.

Up until the time he started his ‘Professional Percussion’ drum shop Frank Ippolito had led an exceedingly distinguished career as a player: a big band drummer. He started playing professionally in 1938 and with the onset of war was immediately conscripted into the ‘Army Air Forces Band’, perhaps more famously known as the Glenn Miller Band. This Service Band had two drummers because the other one, Ray McKinley, was also a front man and compere. In modern terms for Frank it must have been like playing for the Stones or The Beatles.

The band was correctly deemed by the war-time US government to be good for morale and Frank had some interesting things to tell me about it. The band was shipped to the UK to give morale boosting performances to the troops. Frank would appear to have liked the UK while he was here.

Glenn Miller was something of a disciplinarian who, as their commanding officer, not only ordered the band to shave off their moustaches, he had had a very clever way of keeping the band he commanded on their toes. He was forever changing just slightly their musical arrangements, which of course meant that no musician was ever able to get into a rut, since it was necessary to concentrate all the time on that day’s arrangements.

After Miller’s sad and mysterious disappearance the band continued ‘under the direction of Ray McKinley’ only because the whole band blackmailed the US Army by threatening to send all their instruments (which were their personal property) and all their arrangements back to America if they put in anyone to lead the band other than McKinley.

I’ve written about this before but it will certainly stand being repeated because it’s such a good story.

Like many ex-soldiers at the end of the war, Frank fell foul of a law stating that after demob, the GI’s had to be given back the job he’d had prior to the war. This meant that Mo Pertill, Miller’s original peace-time drummer, got his old job back. Frank joined Tex Beneke’s big band among others and eventually got into studio work in New York, playing and enjoying all kinds of music. He had an open mind to anything which was a contributory factor to why he once owned what was arguably the most successful (and exciting) drum shop in the world.

His philosophy to drumming was very direct and simple:

“No matter who you are, and how good you are, you have something to learn from every other drummer”

Once he opened the shop, for my money it was the only place in the world (for quite some time) where you could, given a certain amount of patience, see all the world’s greatest drummers at one time or another. According to Frank himself, the only drummer of note who hadn’t been to his shop at Eighth Avenue and Fifth Street in New York City was Ringo Starr (who I think bought his Ludwig set from Manny’s for the Ed Sullivan show).

Other than Ringo, pretty much everyone – Ronnie Zito, Elvin Jones, Billy Cobham, Max Roach, Buddy Rich, Alphonse Mouzon, Steve Gadd, Kenny Clare, Mel Lewis, Jim Chapin, Lennie White, Bernard Purdie, Ginger Baker, Tony Williams, Gerald Brown, Chico Hamilton – all came into the shop and some of them even helped out there. It simply was not the sort of shop you sent your road manager into – everybody did their ownshopping at New York’s Professional Percussion Center. I was fortunate to see many of my heroes there.

However to draw another comparison, Ivor Arbiter’s Drum City shop in London eventually had pretty much the same sort of clientele, but of course it was 3459 miles away from the Big Apple on the Eastern side of the ‘pond’.

Frank Ippolito’s raison d’etre for starting his shop in the early sixties was to, as he told me: “fill the void left by the death of Bill Mather, the owner of ‘White Way Music’ which was up ‘till then, the best drum shop in New York”.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the name, Bill Mather was a Brit. who was ‘Doc’ Hunt’s partner and who took care of the New York end of the LW. Hunt Drum Company, otherwise situated in Soho’s Archer Street, a stone’s throw from the Windmill Theatre.

According to Frank, Bill was the best drum engineer and drum technician ever. It was Bill Mather who first devised disappearing spurs, the ‘console’ mounted tom-tom holder for the bass drum, and also the shell mounted cymbal arm holder and tom-tom leg block. He invented all of these in the thirties for Gene Krupa, for whom he would shut his basement shop and disappear on the road with, sometimes for weeks. He almost certainly invented the shield with initials on the bass drum for Gene Krupa and was possibly the first drum tech/road manager!

Frank Ippolito decided to take over Bill Mather’s shop with some trepidation and endeavoured to fill the great man’s shoes. As Frank said: “What could be better than being a drummer and owning your own drum shop?” His motto was always: ”Drums for Drummers”.

Frank had a refreshing retailing philosophy that ‘cheap was cheap’ and as such you wouldn’t find ridiculous bargains in his shop, but what you would find was the very best quality drum products – at a very fair price (and it was certainly a fair price for us Brits who were used to happily paying through the nose for American equipment.)

In many cases the equipment had been ‘breathed’ on by Frank’s people. These guys offered the most comprehensive after-sales service you could possibly wish for. If the equipment didn’t live up to Frank’s exacting standards then he simply wouldn’t have any truck with it – whoever made it!

There were some parts and accessories from famous manufacturers which were conspicuous by their absence from Professional Percussion’s shelves since they fell short of perfection in one area or another – these drums would be supplied by Frank without the offending articles attached.

I once asked Frank whether he thought the quality of drums had deteriorated because of the huge demand generated by Ringo, Dave Clark and their pals of the British Invasion? His answer was unexpected since he intimated he was forever arguing with manufacturers about the quality of their products. His attitude then was that, by and large, it was him, the dealer, who should be campaigning for a better deal for his customers. This philosophy was almost the same as his attitude towards retail prices. He strove to get the best possible price from the manufacturer and he did this simply by paying his bills on time. The discount Frank got for his prompt payment was passed on to his customers.

It’s easy when you know how, isn’t it?!

The Professional Percussion Center was actually on three floors of a very old, typical New York ’brownstone’ building. The first floor was the shop proper with the goods on display in an intentionally rather haphazard but somewhat organic way. Frank wanted to keep the feel of the shop ‘funky’ because he felt (quite rightly) that drummers like to buy their instruments from a shop which didn’t look too modern and didn’t appear to be a rip-off. The second floor was absolutely packed, floor to ceiling with drums, heads, cymbals, parts, fittings and cases. The third floor was a storage area full of old equipment and two teaching studios; one occupied by Elvin Jones when he was in town and the other by Jim Chapin. Billy Cobham and Tony Williams had both given lessons here. It seemed many American drummers had had at least one spell of tuition there.

As we wandered through the warehouse, what astonishingly turns out to be something more than 50 years ago, Frank pointed out things of interest: “That’s Gene’s Radio-King set there and there’s Buddy’s old Slingerland there, and there’s Lionel’s original Deagan vibes, and there’s an old Ludwig bass drum on wheels which belonged to Sonny.” These guys certainly didn’t need their surnames when Frank talked about them!

He also had an interesting Ludwig set made during the war when, by law you could only use 10% metal in any project This set had wooden nut-boxes and wooden rims to comply yet still sounded rather good. I think Frank said that was the very outfit he’d used in the Glen Miller band. Having just played Vox’s recently released 2020 version of Trixon’s Speedfire set, I wouldn’t be at all surprised if some ‘enterprising’ manufacturer were to come up up with a replica ‘Rolling Bomber’, ‘Dreadnought’ or ‘Victory’ set’ with wooden hoops and nut boxes, 80 years or so after after the event.

As I said at the top, this month’s subject was to my mind the American equivalent of Ivor Arbiter, although I don’t know if they ever met.

A chap called Al Duffy had a hand in inventing what is now the ubiquitous chain-driven bass drum pedal when he worked in Frank’s shop, and he and Frank took out a patent on the idea. In the beginning it was simply an accessory add-on for Gretsch or Camco.

Al knew Frank, and was in the shop from time to time visiting or whatever and was asked one time if he could put a pedal mechanism on a rack of chimes that he had. He figured, “Yeah, I could do that.” He had a little workshop over in Brooklyn at that time, just for his own personal needs with a place to store equipment. So Al carried the rack back there and built a pedal mechanism on it. One thing led to another and they finally formed an association.

Frank himself was responsible for a practice set which was called FIPS, shorthand for ‘Frank Ippolito’s Practice Set’ It had rubber pads and as usual didn’t make too much noise. Ideal for New York’s apartment buildings.

Frank himself was responsible for a practice set which was called FIPS, shorthand for ‘Frank Ippolito’s Practice Set’ It had rubber pads and as usual didn’t make too much noise. Ideal for New York’s apartment buildings.

In the past I’ve alluded in various magazines to the ‘ones that got away’, and Frank Ippolito had a rather memorable one of these. Picture if you will, a five-piece Camco in red lacquer with gold hardware everywhere and red Evans hydraulic heads. I was touring the US with Argent and had an Amex card burning a hole in my pocket anxious to provide the $700 necessary to complete the transaction. But, for some inexplicable reason, I chickened out, didn’t buy the set and I’ve regretted it ever since!

There was a time when many drum shops had staff who were patiently waiting for their dream gig to come along and sometimes in America they saw fit to employ someone of British extraction in that role. Frank certainly had one, as did several other drum shops in the New World. According to Frank Ippolito the only way to get rid of these guys was to find them a gig!

When Frank died on March 19th, 1978 the shop was run for a time by his wife, Jayne. Unfortunately like many dedicated drum shops, it didn’t survive, no matter how good it was.

It was great to have Pro Perc while it lasted though.

Bob Henrit

December 2020