Bobby Graham

His was the drumbeat behind two of the most famous rock riffs of all time. Bobby Graham was there at the dawn of Britpop, playing drums on The Kinks” breakthrough singles, ‘You Really Got Me’ and ‘All Day And All Of The Night’.

And it speaks volumes that Ray Davies, lyrical and musical powerhouse of The Kinks, called on Graham 40 years later for a “fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants” session, which included a reworking of ‘You Really Got Me’.

Magical moments in musical history.

Yet recognition has largely passed Graham, Britain’s most recorded drummer, by. He acknowledges that was the lot of a session musician in the 1960s.

It could all have been very different had he accepted one drumming job offered to him by Brian Epstein, manager of a certain quartet that went onto rewrite musical history and set new standards bands are still following. While John, Paul, George and Bobby doesn’t have the same ring to it, if you pardon the pun, as John, Paul, George and Ringo, his future may have brought a lot more fame had he joined The Beatles after the ousting of Pete Best from the drum stool.

“That’s the one thing people write about me,” he says, possibly a bit weary of the fact that despite the wealth of hit songs, movie scores, television themes and jingles he played, one decision made in his early 20s is constantly raked over.

This is the man who played on ‘We Gotta Get Out Of This Place’ by The Animals; Dave Berry’s ‘The Crying Game’; Petula Clark’s ‘Downtown’; Dusty Springfield’s ‘I Only Want To Be With You’ and thousands of others.

His estimated 15,000 sessions are testament to his worth as drummer. ‘You Really Got Me’ wasn’t his first, or his first “hit”, but it cemented his reputation.

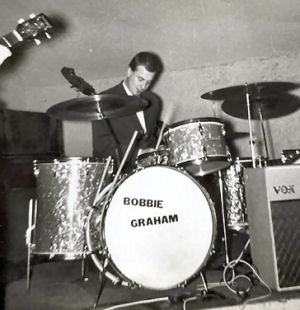

Bobby (or Bobbie as it was then) with Joe Brown

“I think they had already recorded it before, and it hadn’t quite got what they were looking for. If I remember right, The Kinks had released a couple of records and hadn’t really done what they expected. ‘You Really Got Me’ was like their last chance in a way.

“I supposed I got the call because of Shel Talmy. I’d worked with him before. He used to use me on a lot of stuff. Mick Avory [Kinks drummer] had just joined the band and I just got the call to go to the studio. Mick was there. There wasn’t a problem.

“I turned up and did four tracks with them. I did ‘Long Tall Sally’ with them, which I think was their first single.

“Looking back, The Kinks were my favourite band to work with. The structure of Ray’s songs was so very different to anyone else at the time. Most of the sessions I played on were easy to play. With The Kinks the music wasn’t hard to play, but you had to think about the lyrics. They were important.

“That flam at the start of the song was more by accident that anything else. They counted it in, the guitar started and I hit the snare so hard the stroke became a flam. Everybody liked it.”

So much so that Graham was called back to do other Kinks’ sessions. ‘All Day And All Of The Night’ was another hit to showcase his drumming talents, for example.

“Ray was such a deep introverted thinker. The last session I did with Ray was after I got a telephone call from him out of the blue. “Hi, it’s Ray,” he said, and I said: “Ray who?”

“He asked if I could go down to Konk Studios and re-record ‘You Really Got Me’ for his solo album. When I got there he said he was going into a vocal booth. He had this song in his head. There were no lyrics so he just started humming it. He was telling me what he wanted to play. Things like “go to ride cymbal now”. It turned out to be Storyteller, the title track of his album. When I heard it, it started off with just drums.

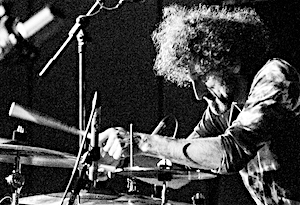

Bobby more recently

“I thought it was the weirdest session of my life. But Ray is a genius. It was a lot of fun. I was delighted to have been asked. Working with him again after all that time was great.”

With most journalists concentrating on The Beatles’ link to Graham, he appears delighted to talk about other sessions and there is no doubting his fondness for The Kinks.

“Everything was always a gem,” he adds. “I played on Dave Davies’ ‘Death Of A Clown’, too. It was so good. I think The Kinks used me because I interpreted the music the way they wanted. I guess I was lucky, but I felt it was so easy. The music was great.

“I was born with a huge natural feel. It’s a gift; something you can’t learn. It’s the way I play. I could say it’s the only way I play, but I’ve been lucky that it worked for me. People wanted me to play on their records.

“As a session drummer you can get a bit bored sometimes. Especially the third session in a day, when you’re tired and want to go home. But that’s when you’re on autopilot and you know that you’ll do the job people want you to do.”

The lot of a session musician had pros and cons, remembers Graham. On the one hand, the money was good, but until a few years ago, paid then and there and with no royalties. But the legacy is questionable. Graham laughs that he and other sessioneers have claimed the same hits.

“We couldn’t all have played on the hit version,” he laughs. “Clem Cattini [another in Mike Dolbear’s British Drumming Icons] said he played on Tom Jones’ ‘It’s Not Unusual’, but I know I was called to that session. I used to pull Clem’s leg about it.

“I always swore I was the drummer. But it turns out it was Ronnie Verrall. I had played the song with Tom about a year before. It was a slightly different arrangement. However, it wasn’t me. Or Clem. We both played on a lot of sessions but nothing was written down for the most part. You think you played on whatever song and it turns out it was someone else.

Bobby recording

“Although, and I’m not making this up, I can generally spot my style of playing. It’s like my signature. I was wrong about It’s Not Unusual, but not much else.

“The truth of the sessions is probably better known now than any other time. It only recently was revealed that I played the drums on all the Dave Clark Five records, for example. That fact was hidden and I didn’t mind. It didn’t make me a fortune, but I didn’t feel aggrieved in any way, that the stuff I played on made a lot of people rich.

“We were being paid a hell of a lot of money back then. My rent money was about £5 a week in the early ’60s and I was getting £7.50 a session. I drove a Jaguar, had a lovely home; I can’t knock it.”

Session work is paying today. A few years ago, Graham started being paid royalties for some of his session work. “It’s nice to get a bit of money now, but that’s a bonus. I didn’t expect it.”

Drumming appeared to choose Graham, rather than any decision to play drums. “I was always fascinated by drums,” he recalls. “The look of them, the sound of them. I would sit at a table as a kid banging away with my knife and fork.

“And when I bought my first proper kit, that was it, I was into drumming and would never stop. My first kit was a right Heinz 57. It was from Ted Warren”s drum shop in Bow, London. It was a mixture of bits of everything.

“The first proper kit I bought was an Ajax, then I moved over to Carlton. They gave me a kit free and I used that on most of the recordings.”

Graham didn’t start out to be a session musician. His first big break came with Mike Berry and The Outlaws, where he was also musical director. He did ‘Johnny Remember Me’ [for Johnny Leyton] and then got offered the first of many sessions.

“I was with Joe Brown and the Bruvvers. He and I never saw eye to eye. He was a disciplinarian and I needed that because I was a wild child. I was at Pye Studios and people saw me. Gradually my name, my reputation, built up.”

Bobby with Brian Bennett, Clem Cattini and Steve Smith

Working with Tony Hatch among others, Graham was thrown into the musical melting pot with Big Jim Sullivan, Mike Leander and a young Jimmy Page.

“We did all the pop and all the film sessions. At the time I couldn’t read music. With drums you can basically bluff it in many ways. Buddy Rich couldn”t read but would listen to the band.

“Over the next two or three years I learned to read. In fact, the musical directors never bothered to write music for me. They would write out the bits and put “Bobby fill”. I also used headphones with the whole orchestra and vocals. Whenever the vocals stopped I put something in.”

Session work included Van Morrison’s ‘Them’, playing on Gloria and ‘Here Comes The Night’. “He never wanted session musicians on his songs, he thought his own musicians could do it, but I enjoyed those sessions.

“I loved working with PJ Proby. He was a great guy. You never knew what he would do next. You didn’t sleep on his sessions. It was all about feel and where he felt the music should go at any time.

“I was very lucky that I had really good technique. I had started out as a jazz musician so knew my paradiddles, but it was always feel for me.

They said the same thing about Jimmy [Page].

“It was very exciting. One of the strange things about sessions was that you never knew what you were going to do the next day. The fixer would ring me up and all he would say is what studios and when. He wouldn’t tell you who the session would be for.”

This was to ensure an honest approach to every track, although Graham says that wasn’t necessary. “We were professionals. It was our job to get it right, do the job the way they wanted us to. It didn”t matter who it was for. It was also our reputation.

“You knew you were expected to give 150 per cent to each job. I was only about 20 years old, suddenly I would be sitting with guys like Don Lusher, my idol from the Ted Heath Band.”

The breakneck lifestyle, exciting in the hippest of musical decades, was also taking its toll on Graham, though.

“I didn’t believe in myself,” he remembers. “I was Bobby Graham, from Edmonton. I was mixing with these incredible people. Friends of mine tell me that they have heard me four times in the last hour on the radio. It still doesn’t seem real in many ways. I started drinking heavily.”

Alcohol affected Graham’s career just as a new generation of session drummers were making their way onto vinyl. But he’s been sober for 36 years, and despite the arthritis in his hands, is still playing whenever he gets an opportunity.

“I love playing,” he says. “It’s what I’ve always wanted to do.”

And The Beatles? “They were unheard of when I was asked to join. I was making a good living and didn’t want to give it up to play in a Liverpool band nobody knew anything about.”