If after you’ve read this, you want to see an Instagram chat that Mike recently had with Geoff, click here…

If your CV includes names like Robbie Williams, Tina Turner, Rod Stewart, Will Young, Ronan Keating, Richard Ashcroft, Demi Lovato, Killing Joke, Dido, Johnn y Hallyday and Natalie Imbruglia – just to name a few – you know you’re doing something right.

y Hallyday and Natalie Imbruglia – just to name a few – you know you’re doing something right.

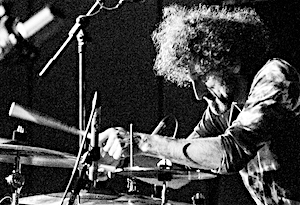

If you have also played on over 50 number one’s and 90 Top 20 albums worldwide, you’re certainly one of the top session drummers out there – and your name is probably Geoff Dugmore.

His humble and professional character paired with a chameleon-like ability to work with different artists from all styles has made him one of the most in-demand, not only in the UK but all over the globe.

I had the pleasure of meeting Geoff after his teaching day at the Ultimate Drum Experience 2016 and spoke to him about his early days of drumming, his work in the studio and much, much more.

As a kid you started off playing the guitar. What made you choose the drums after all?

Yes, I was ten years old and desperately wanted a drum kit but my parents didn’t let me have one, but they did buy me an electric guitar. I was so desperate to have a drum set so I swapped my guitar with a guy from school with a drum set. I brought home this old Premier kit with calfskin heads and I was just in heaven. I set it up in my bedroom next to my two speakers and I would just put my favourite records on and just play along for hours and hours.

You never had any lessons, is that right?

No, I’ve never had any. I was in a pipe band at school and we had, I guess, very limited lessons in pipe band drumming but nothing to speak of. I never did anything in terms of grades, learning about rudiments or any of these things. Everything was just by ear. I would just listen to something and try to find a way to copy it.

Do you think that could be part of the key to your success?

Do you think that could be part of the key to your success?

I’ve come to believe that the most important instrument we have is our ears and when I listen to a song I’m very acutely aware of everything that’s going on in the song. I’m very aware of the rhythm of the guitar for example, and getting inside that rhythm, feeling whether the guitarist is playing in front, behind or on top of the beat. Any of those kind of things. I’m acutely aware of the melody too. When I play drum fills I’m always playing with the melody, I’m never crossing the melody, so there is no clash. For me it’s all about playing what’s the best thing for the song.

I never thought about it like that but now that you bring it up maybe it does have a bearing on why I managed to play on a lot of records. Maybe it’s something that people pick up on and feel.

The thing about this business is you can’t bluff. You have to be completely committed to it. I think people who are artistic have heightened senses. They can feel emotions where the highs are incredibly high and the lows are incredibly low. If you’re giving everything to a project – which you always should for yourself as well as for the artist – then I think it’s something quite infectious.

You moved to London with your first band ‘The Europeans’.

Yes. We weren’t called that when we moved actually. There was four in the band, a lighting guy and a sound guy. We had a van and a little PA and we all moved to London together when we were seventeen. For the first six months we slept on the floor of a friends basement flat in Camden Town and then managed to graduate to eight of us living in a two-bedroom flat in Neasden. When I look back on it in a lot of ways these were just such fantastic times because we had absolutely nothing but a sack full of dreams. That was it. We wanted to make music, get a record deal and just kept working hard. We met a wonderful producer called Trevor Vallis who took us into the studio to do some demos and then one thing led to another. We had two managers who kept saying that nobody is interested in us so we got a bit deflated, but we kept pressing ahead and trying to get gigs.

One afternoon the bass player and myself wandered into A&M records on New Kings Road and managed to persuade the receptionist to give us an appointment with the A&R guy there called Wally Brill. We played him two songs and showed him one picture of us and he offered us a record deal on the spot. It just goes to show the power of the enthusiasm of the people that are actually making the music. A lot of the times I wonder if managers are not necessarily misrepresenting but maybe what they are after isn’t what the artists are after.

I actually think that’s a really good point. Especially nowadays where everyone is just a Soundcloud link.

Yeah exactly. There is nothin personal in it. When you actually go in there with the enthusiasm, it’s a very infectious thing.

Of course once A&M were interested all the other labels became interested too. We decided to stay with A&M because they were the first and we felt that was the loyalty and at that time that was one of these labels you kind of dreamt about being on. For us it just couldn’t get any better than this.

Where did it all go from there? How did you slip into the session side of things?

Where did it all go from there? How did you slip into the session side of things?

The band did three albums and then it ended for various reasons. That was extraordinarily heartbreaking. You’ve got to remember it was the same core of three of us that had known each other since we were about 10 years of age. We grew up together, we had gone through all of this stuff like simply growing up together then moving to London, getting a record deal and so on. At this point we were about 24 and I just had no clue what I was gonna do. I was very fortunate that another A&M artist called Joan Armatrading listened to a lot of the stuff I had done with my band and called me to ask me to play on her album. At this point my concept of a session musician was somebody that played in the West End. I didn’t really grasp that session musicians went to play on artists albums. Coming from the band perspective I just wasn’t aware of it.

Halfway through recording her album another producer Nick Launay called me and asked me to come down to New Zealand and Australia to work with the Finn Brothers, so I went and did that.

That led to something else and so the whole snowball effect happened, I began to know more musicians, producers and studio engineers on the scene and one thing led to another.

Do you mainly record nowadays or do you still play live a lot too?

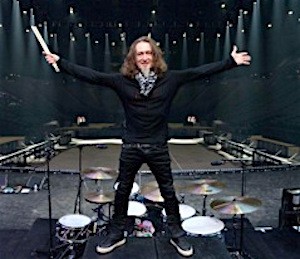

It’s a combination of the two to be honest. I’ve been extraordinarily fortunate to play on a lot of albums by the most diverse and incredible artists. Not only in the UK but I’ve been fortunate enough to work in the states, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, China… all over the place. I think of myself of being one of the luckiest musicians alive. I still wake up in the morning and pinch myself: “Is this really true, am I still doing this?!”.

Live vs. studio?

Oh, two completely different disciplines.

I love the studio from the creative perspective, I just adore that. I love to create and recently actually got into producing things too. There’s a bit of psychology involved in that, I love that too. Having worked with so many amazing producers over the years you kind of see which ones do great things and how they inspire people.

Live – you can’t beat live for the sheer excitement and adrenaline rush.

So I guess in an ideal world you’d spend six months of the year doing one and six months doing the other but it doesn’t always turn out like that of course.

The thing about it is nowadays I can be on tour somewhere and a producer would just call you and ask you to find a little place to pop into and record some drums for this and that. So you find a studio to lay down some drum tracks in the morning and just send the files over. That’s just how the recording process has changed.

Has the balance between the two changed for you over the years?

Has the balance between the two changed for you over the years?

I think now it’s definitely more live based than it is studio based. There are still a lot of records being made but perhaps the whole budget structure has changed now. For example when I started you would spend three weeks to cut 12 backing tracks, but for example on the new Richard Ashcroft album that’s just come out we did 30 tracks in four days. That’s the kind of difference.

Having said that, you have to be on top of your game to be able to do that. You’ve got to think very creatively very quickly, you gotta have your sound together.

You’re listening once down to the demo, you’re mapping it out, you’re thinking parts, sound, style – all these different things. It’s like multi-tasking in your brain. I guess maybe that’s to a certain degree why people call you, because you have the experience – because you gain the ability through experience is probably a better way to say it – that you can apply all these things when you’re in the studio.

Do you think up and coming drummers nowadays still get much chance to gain that studio experience? After all, the sessions get less and less and as a producer I would always hire one of the greats.

You know, I think it’s sort of historical like that. If you look back to Bob Henrit and Clem Cattini, the next generation came after that, and the next generation after that. There will be another generation after us but who they’re gonna be maybe isn’t quite defined yet.

The way the industry is now, the sort of wheat from the chaff, if you like, is very quickly distinguished. As I always say to people: the thing about being a session player is probably 65-70% your ability to play, the rest is personality. It’s so key! In some ways you’ve got to be a bit of a chameleon. You can be working with one artist who has a mindset in one way and then the next day you’re working with somebody entirely different and you’ve got to get inside that. Again it’s all these different abilities. I know a lot of drummers are obsessed by technique and all that kind of stuff but at the same time you’ve got to know the realities about being a working musician. It’s not just about how fast you can wiz around the drum kit. In the pop/rock studio arena like Ralph [Salmins] does, like Ash [Soan] does and like I do, you’re never gonna get asked to play a drum solo, it just doesn’t exist. You’re gonna play bass drum, snare drum, hi hat, maybe one tom and a crash cymbal. I was talking to Ash about this earlier and we were saying: master the groove and you will work. Whether you’ve got a regular job and you’re just playing on the weekends or you play full time – you will always work because you’re able to hold the whole thing down and play songs. Playing songs is the key to longevity in the music business as a drummer. I’m absolutely convinced of that. You can do all the other stuff for your own enjoyment but that’s the serious core of it.

You’ve played for so many top artists from all genres. What’s the key?

The key is understanding the artist you’re working with and getting inside their head quickly. It’s a bit like being a chameleon in some respects. You’ve got to go into their world, understand their world and be sympathetic to their world. I think that’s the key.

It’s the same when you go to work with artists who maybe don’t speak English. I think of that, as for example, as if somebody is deaf or blind – the other senses are totally heightened. If you don’t have that language thing to go by, your musical senses are really heightened. You listen far more acutely for some signs, feeling, emotion that you can interpret and go: “Ok, I pretty much understand what is needed here”, and you play accordingly. I think being a session player you really got to be able to open your heart emotionally to understand what it is the artist is looking for in order to give the best you possibly can for their songs.

You’ve also done a lot of work in China?

You’ve also done a lot of work in China?

Yes, I’ve been fortunate enough to be invited out there in 2014 to work with an artist called Xuwei who’s the biggest rockstar they have in China. The guy who did it prior to me was John Blackwell who then went to play with Prince. They heard some of the stuff I had played on and asked me to come out, so I decided to go for one month to see how it goes. So you’re arriving in a rehearsal room with 12 other musicians and nobody speaks English. Ok, you had the set of songs but that’s only one thing, now you have to sit down and play and interpret it with these people. It was challenging because all I had to go on was for example the body language of the singer as he was singing the song, and you’d be computing that in your brain as you’re playing, trying to watch how his arm and wrist movements was with his guitar, trying to just get inside it. I generally play a lot by gut instinct and not really analysing too far, so I was fortunate that I just seemed to tune into his zone.

They really wanted an English vibe on it. Unlike Japan where most of the influences are all American, in China most of the influences are British music. I think that’s one of the reasons that was one of the reasons why they decided to change from an American to a British player.

There is a lot of music being made out there and the thing is that we’re working in a global industry. It’s not just that music is being made here, there is music being made by artists all over the world. Don’t just think everything happens in one place. Don’t be scared to go and experience not only the musical culture but also the culture of the people. It all goes into the making of the person you are.

You’ve also worked on the very first Robbie Williams tracks after he left Take That. How does it feel to have been involved in those early stages of making a world famous rockstar?

After Rob left Take That he embarked on doing solo stuff. We were working in a spire of a church near Caledonian Road in North London with Guy Chambers and Steve McEwan. Guy and I knew each other quite well from working on other projects where he was the keyboard player. So we were making demos with Rob and finding the sound and direction all this stuff and later went in to make his first solo album. Unfortunately from my point of view I didn’t make the first tour because I had already promised somebody else to work for them and it clashed. I’m not the kind of person to jump ship, I think it brings bad karma. So fair enough, I probably lost a hell of a lot of work, but that’s life. Put it behind you and don’t cry about it. It could be that I said yes to two days work and somebody phones you up and offers six months but it’s not in my DNA to do that. If I committed, I committed. I stand by that because I just don’t think it’s the right thing to do.

It’s phenomenal what Robbie achieved, it’s phenomenal what Guy achieved and it’s phenomenal what they achieved as a team. I never begrudge anybodies success, it’s fantastic. All credit to anybody who does something successful.

I’ve seen Rob a few of times since. For example we did a project for an act called One Giant Leap who are two guys who went around the world for a year recording local musicians in very obscure places and then put a concept album together where amongst others Rob sang on. It was great seeing him again. He’s always been such a gentleman. A real fun, cool guy, I like him a lot.

You played on over 50 number one’s. Any session that stuck out?

Er… well, they all have sweet spots for different reasons. I mean, every session I’ve ever done has a happy memory attached to it and I’ve kept a diary of every session I’ve ever done, and what happened on it, what I’ve used, how we did it and so on. One day when I’m ready and I think anybody might be remotely interested I might throw it out there.

Do I have a favourite? Maybe Tina Turner.

Do I have a favourite? Maybe Tina Turner.

We were cutting an album called ‘Foreign Affair’ which went to number one, at a place called Easy Studios which doesn’t exist anymore sadly. She cut one of the songs and then came into the control room. We had the monitors blazing, she just sang along and she was still louder. I was just blown away. My first meeting with her – in hindsight it was probably a bit of an audition. She came in and had this little miniskirt on. She stuck her leg up on the chair and said: “Feel my thighs, I’ve been working out.”. I was kind of like well, do I do this and be a man or do I say no thanks and come across the wrong way?! Anyway, I did and said: “Feels great Tina!” and she said: “You can stay!”.

I suppose in a way that was a really sweet thing that happened but every single session is a great memory.

You’re a bit of an equipment collector.

Yes, a little bit. I’ve got nine or ten kits, so not masses, but I have a lot of snare drums. In fact, I think my pride and joy snare drum is a 1921 Leedy with the gun metal and the carving rings around the shell. That has its original calfskin head and the original snares on it. I bought that in Cleveland in, I think, 1991 and it’s one of those drums that I don’t really play that often, but sometimes I just take it out and admire it because it’s gorgeous!

Tell me about your ‘5-P-Plan’.

Ah yeah: Proper Planing Prevents Piss-poor Performance. That’s exactly it.

If you got everything together and planned out, it eliminates many potential problems that might come. For example if you go and do a session, take extra things that you might not necessarily think might be useful, but you never know. I always take two or three bags of percussion. I take my Hammered Dulcimer which is kind of like a table with metal strings across it and you play it with two little wood hammers. I think it’s half Greek half Celtic. Surprisingly I’ve used it on so many sessions I took it to because it’s not something you usually hear so it adds an interesting sound.

I read you always bring some ‘decorative items’ to your sessions too?

Yeah, I take some rugs and candles – it kind of focuses the energy into the drums. It’s one of those things that just creates a really good atmosphere in the studio rather than having stark sort of school-lighting which is really not very conducive to a vibe of any description. I like to create a vibe in the studio, so I take all that stuff with me just so that it’s going into a home atmosphere rather than working in a stark studio atmosphere. It’s one of those things that’s just grown over the time and people seem to like it and respond to it. It’s a lot of fun to have around. That and the equipment is a lot of stuff to carry around but if you do something do it properly, don’t just do a half baked version of it.

I’m back out on tour. I’ve been on tour with a French singer called Johnny Hallyday. I finished in China last March and went straight to L.A. (which was a bit of a culture shock) to start rehearsing with Johnny. The drummer that was doing the gig before me was Abe Laboriel Jr. and I took over when he joined McCartney in 2006 and been doing his tours since then. I had done four albums for Johnny before, but Abe was his live drummer. It’s a really fun gig and Johnny is a great guy to work with.

So I’m back out with him till the end of August and then I’ve got a couple of albums to do in town and then I’m off to Asia again. That will be the rest of my year.

Thanks a lot for your time Geoff!

Always a pleasure!

Interview Tobias Miorin

August 2016