Okay, so here’s another subject which might initially seem rather boring and inconsequential, but is actually very important for the feel (not so much sound, importantly) of your electronic kit.

Okay, so here’s another subject which might initially seem rather boring and inconsequential, but is actually very important for the feel (not so much sound, importantly) of your electronic kit.

So what we actually mean by a dynamic curve?

Well, if you think about playing an acoustic drum, when you hit quietly, the drum responds quietly too. When you hit hard, the drum is loud. Simple and obvious.

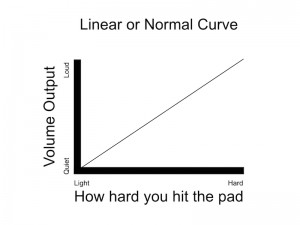

Now, if you were to draw a graph (like the one on the right) to show how the drum responds in volume to how hard you hit it, (with say how hard you were hitting along the bottom line, and how loud the drum was on the upright), you’d expect it to show a straight line. In other words, as you started hitting harder, the drum would get proportionally louder too. This is called a Linear (Roland and Alesis) or Normal (Yamaha and 2box) curve (but its actually a straight line) and it is probably the most used dynamic curve on electronic kits. It obvious and it is how everyone expects a drum to respond.

Now, if you were to draw a graph (like the one on the right) to show how the drum responds in volume to how hard you hit it, (with say how hard you were hitting along the bottom line, and how loud the drum was on the upright), you’d expect it to show a straight line. In other words, as you started hitting harder, the drum would get proportionally louder too. This is called a Linear (Roland and Alesis) or Normal (Yamaha and 2box) curve (but its actually a straight line) and it is probably the most used dynamic curve on electronic kits. It obvious and it is how everyone expects a drum to respond.

That probably seems pretty obvious, but it’s not always the case. Unfortunately the human ear doesn’t always hear things as linear curves as it is effected by other things happening at the same time, such as loud noise or total silence.

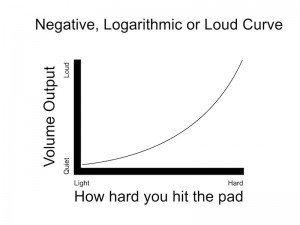

If you were playing drums with a band in a very loud room, most medium and quiet hits would probably be lost, especially to the other musicians. But you would probably be able to hear them sitting behind the kit. When you wanted to accent a certain phrase or fill you just have to pay that little bit extra loud just to make it cut through. So in that situation, how you would be hearing the drums would be more of a curve where just the last, extra loud hits are the ones that will be heard. To recreate this on an electronic kit, you’d have to use a dynamic curve which was flatter for the quiet and medium hits, and went much more steeply up for the loudest hits. This is called a Negative (2box) curve (negative as it spends most of the time below the ‘linear’ line), exponential (Roland and Alesis), or Hard (Yamaha) curve. Three different names for the same thing.

If you were playing drums with a band in a very loud room, most medium and quiet hits would probably be lost, especially to the other musicians. But you would probably be able to hear them sitting behind the kit. When you wanted to accent a certain phrase or fill you just have to pay that little bit extra loud just to make it cut through. So in that situation, how you would be hearing the drums would be more of a curve where just the last, extra loud hits are the ones that will be heard. To recreate this on an electronic kit, you’d have to use a dynamic curve which was flatter for the quiet and medium hits, and went much more steeply up for the loudest hits. This is called a Negative (2box) curve (negative as it spends most of the time below the ‘linear’ line), exponential (Roland and Alesis), or Hard (Yamaha) curve. Three different names for the same thing.

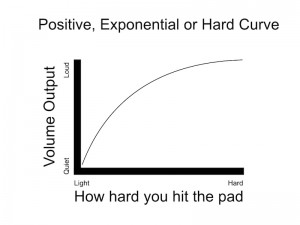

The opposite of this is if you are playing in a really quiet studio with no background noise. Your drums will seem much louder and there will seem to be a much greater difference between very quiet and medium hits. You probably won’t even need to hit very loud to hear yourself very clearly. To recreate this on an electronic kit, you would need to use dynamic curve which went up more quickly at the low end of your dynamics and flattened off as you got louder. This is a Positive (2box) – as it spends most of its time above the linear line – or Logarithmic (Roland and Alesis), or Loud (Yamaha) curve. Again, three different names for the same thing.

The opposite of this is if you are playing in a really quiet studio with no background noise. Your drums will seem much louder and there will seem to be a much greater difference between very quiet and medium hits. You probably won’t even need to hit very loud to hear yourself very clearly. To recreate this on an electronic kit, you would need to use dynamic curve which went up more quickly at the low end of your dynamics and flattened off as you got louder. This is a Positive (2box) – as it spends most of its time above the linear line – or Logarithmic (Roland and Alesis), or Loud (Yamaha) curve. Again, three different names for the same thing.

But the actual room itself can also effect the dynamics of an acoustic drum kit. A dry, dead room will make your acoustic drum kit sound much more like it has a Positive curve on it, where as a massive, cathedral type building will have a more Negative curve feel. It doesn’t actually change the velocity curve but in our heads it will sound like it does.

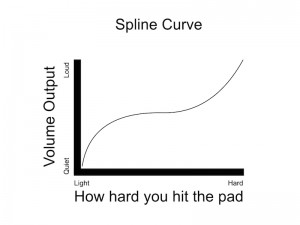

Then, just to confuse the issue, there are other shaped curves as well. Spline curves (with their distinctive ‘S’ shape) are curves which start building up quite quickly at the low (quiet) end like a positive curve, then even out so they are more flat and then ramp up quickly towards the top end (like the end of a negative curve). These are good as they have good control of the dynamics at the low and high end and are fairly even in the middle where we play most of the time.

Then, just to confuse the issue, there are other shaped curves as well. Spline curves (with their distinctive ‘S’ shape) are curves which start building up quite quickly at the low (quiet) end like a positive curve, then even out so they are more flat and then ramp up quickly towards the top end (like the end of a negative curve). These are good as they have good control of the dynamics at the low and high end and are fairly even in the middle where we play most of the time.

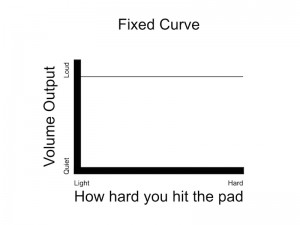

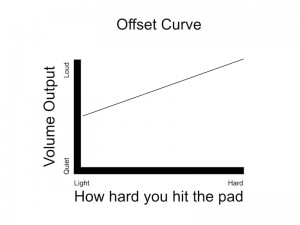

There are also curves like ‘Constant’ or ‘Fixed’ where you get the same volume regardless of how hard you play (good for when you are triggering loops and want them to be a consistent volume), and others called things like Offset where there is only minimal increase in volume from a quiet which is already raised (difficult to describe but look at the picture). There used to be a craze in the ’80’s and ’90’s for modules to have a Reversed curve where quiet hits gave a loud output and loud hits were quiet. Why anyone would ever want that has never been fully explained. I’ve always filed that under “We can so we will!’.

There are also curves like ‘Constant’ or ‘Fixed’ where you get the same volume regardless of how hard you play (good for when you are triggering loops and want them to be a consistent volume), and others called things like Offset where there is only minimal increase in volume from a quiet which is already raised (difficult to describe but look at the picture). There used to be a craze in the ’80’s and ’90’s for modules to have a Reversed curve where quiet hits gave a loud output and loud hits were quiet. Why anyone would ever want that has never been fully explained. I’ve always filed that under “We can so we will!’.

So what has this all got to do with us electronic drummers? Well, changing the curve of each pad can dramatically increase the realism in certain situations. I know that not all drummers want their electronic kits to behave like an acoustic kit, but I firmly believe that most do. For those that do, playing around with velocity curve can really personalise the kit to suit the way they play.

So what has this all got to do with us electronic drummers? Well, changing the curve of each pad can dramatically increase the realism in certain situations. I know that not all drummers want their electronic kits to behave like an acoustic kit, but I firmly believe that most do. For those that do, playing around with velocity curve can really personalise the kit to suit the way they play.

One strange thing that I have noticed over the years is that just because, say, the snare drum feels better with a slightly positive curve, doesn’t necessarily mean that all the other drums should have a similar positive curve. I have found that smaller toms benefit from a different sort of curve to larger toms – in other words the ‘rack toms’ on an electronic kit often need a different curve to the ‘floor toms’. Also, by changing the curve of the bass drum we can make it sound more even and more consistent but still with some dynamics, almost like it is going through a nice expensive limiter in a studio.

Cymbals are another thing altogether. If you think about how most drum kits are recorded, the overheads are highly sensitive condenser mics which usually go through some nice compressors to even out the dynamics. You can mimic this on an electronic kit by changing the curve of the cymbals for a more positive one. Exactly how much more positive is down to you, and personal taste. Just don’t make everything just LOUD though!

I have even set up kits before for drummers where it ended up that each pad, whether it be a drum pad or a cymbal pad, used a different curve to give the drummer the feel that they wanted. It really is down to the player’s personal choice.

So in my grand plan to get drummers improving the performance of their kit, after setting the gain correctly and adjusting the threshold to suit the situation (see previous articles for this), then setting the correct velocity curve foe EACH pad comes next and is just as important.

So if you find yourself this month doing Yoga and lacking a mantra to chant, you could do a lot worse than repeating to yourself “Gain, Threshold, Curve… Gain, Threshold, Curve…”.

All together now…

“Ommmmmmmmmm….”

Simon Edgoose

March 2018

Simon Edgoose got his first electronic drum when he was 13. Since then he has toured and recorded as a performer, but has found that things have led him to become more of a programmer, consultant and demonstrator for the biggest names in the business. He is worryingly enthusiastic about all forms of electronics and is on a mission to stop acoustic drummers feeling threatened by electronics and see them as a really useful tool. He started the website www.eDrumInfo.com when he realised that many electronic drummers were all having the same issues which could be easily and quickly sorted out.