We are all so used to using loops now in music that we don’t really think about where they actually come from. By that, I don’t mean who records them and stuff like that (generally musicians like you and me), more like why we have got used to using short repeating sections of music to make other music from.

We are all so used to using loops now in music that we don’t really think about where they actually come from. By that, I don’t mean who records them and stuff like that (generally musicians like you and me), more like why we have got used to using short repeating sections of music to make other music from.

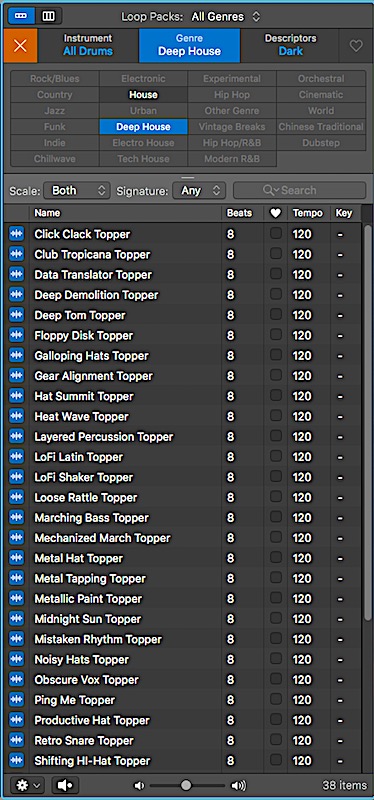

You only have to open up Logic, or Ableton, or GarageBand and you are faced with thousands, upon thousands of different audio loops covering different genres, different tempos and different feels.

But how did this come about?

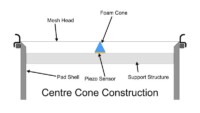

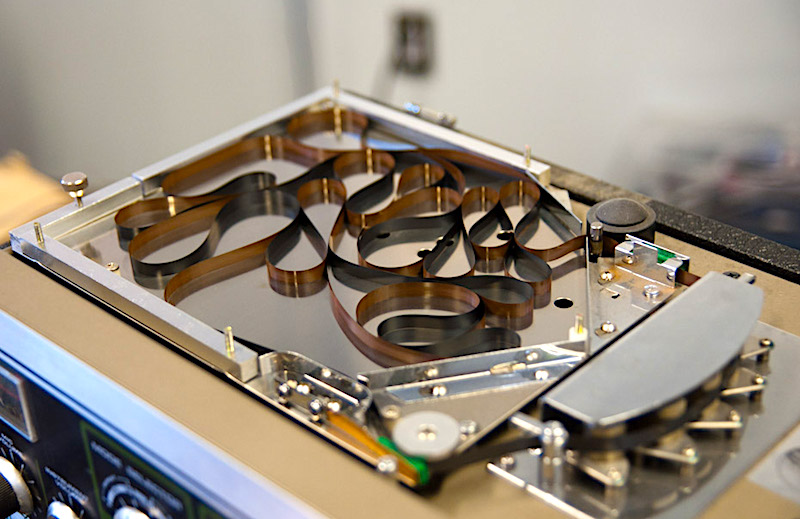

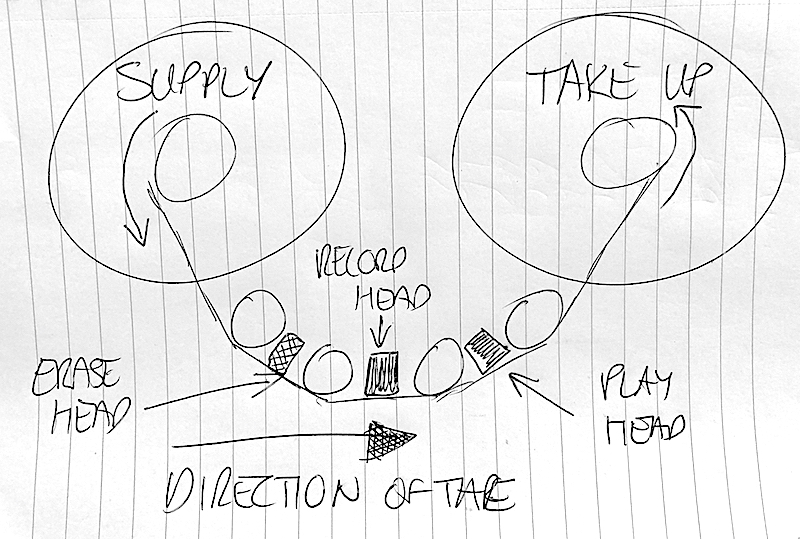

Forgetting all the classical musicians who messed about with tape recorders in the 1940s, this way of working using taped sections of music on repeat probably first appeared in the Jamaican dub scene of the 1960s. Dub features, pretty heavily, slap-back echos, which were done back then on tape echo machines. These had a loop of magnetic tape inside, and the speed at which they travelled could be adjusted by changing the motor speed. The signal (a sounds, hit, etc) would be recorded onto the loop, and allowed to travel around its wheels and capstans until it reached the playback head, whereupon it would be heard again, at a fixed time after the original. This gave the classic slap-back (or fast single repeat) effect.

https://youtu.be/JZ-yp2cCGbQ?t=274

Usually, at that point, the tape would pass over an erase head, which wiped the magnetic information so it was clean for the next sound to be recorded onto it. However, if this erase head was turned off, the tape would go around again and anything which subsequently was played into the tape loop would be recorded on top of it, and both signals would be heard next time the tape went over the playback head. Cue instant Dub.

This ‘sound on sound’ method gave us a totally new way to build music, as well as also being the name of the long running popular recording magazine in the UK.

This ‘sound on sound’ method gave us a totally new way to build music, as well as also being the name of the long running popular recording magazine in the UK.

But going back to the method, by changing the loop length and the tape speed, different loops could be created and played back, leading to many thousands of classic dub tracks, and all this was happening some 60 years ago.

Of course, many others at the time, including the Beatles and Frank Zappa, were using tape to come up with weird and wonderful tracks (check out The Beatles – Revolver, ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’), but this was more reversed tapes, or loops of Paul laughing, rather than drum grooves.

Pre digital, everything was recorded to magnetic tape. The audio that was being recorded was converted into an electronic signal and the electronic signal caused to magnets to move the position of magnetic particles on the tape. When the tape was passed over a playback head, the music that was originally recorded would be heard.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QXNoUHdFyrQ

The only problem with this was that the tape was very fragile, would stretch easily, and could be destroyed in a fraction of a second if one of the wheels or ‘capstans’ in the tape machine got anything remotely sticky on it (no sneezing near the tape machine!). It also degraded so quickly, simply by playing on the very machines it was designed to be played on, that it is said that every seven plays lost half the audio quality. You can hear this degradation on early tape delays, where each repetition would lose its high end and become more muffled.

The positive side of tape, was that it was cheap, easy-to-use, and could easily be cut with a razor blade and different sections could be stuck back together in a different order – early editing.

The positive side of tape, was that it was cheap, easy-to-use, and could easily be cut with a razor blade and different sections could be stuck back together in a different order – early editing.

When the disco hit popular music in the 1970s, the demand on drummers became totally different from the rock scene that preceded it. Before, drummers could play as they liked, the crazier the fill the better, keeping tempo wasn’t so important. To be honest, things were pretty relaxed.

Now drummers had to play with a certain intensity (no relaxed, laid back disco grooves here!) and drum fills were something that happened once or twice in a whole song, not every 8 bars, as before.

Drummers that could play the same groove round and round for five minutes at a time were very much in demand (12” extended mixes were very popular). While playing for this long might sound like a relatively easy thing to do, it is actually incredibly hard to play for five minutes, non-stop, with the same intensity, integrity, and intention, without changing the groove, doing a fill, or hitting a cymbal. Try it.

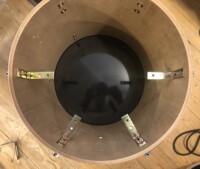

Larger tape machines were available, so the drum groove would be recorded first. Then everything else would be layered on top to make the final track, and we still record this way today usually.

As the amount of drummers who could do this successfully was small, studios had to look for other ways to achieve it.

Engineers would find 2 or 4 bar sections of drums (with or without bass, percussion etc) and chop (or ‘splice’, hence the name Splice.com of the loop website) them out, and connect the ends with special adhesive tape so they made a loop of tape. When played these ‘loops’ would have an endless drum groove, with no deviation – perfect for building your disco classic on.

This became the new ‘norm’ and wasn’t just in disco. Check out The Sweet – Air On ‘A’ Tape Loop, which has what sounds like two tape loops – a guitar phrase that starts the piece, and another which is the one bar bass and drum tape loop running through the rest of the track.

Of course, all this was just a moment in time.

Despite drum machines having been around since the 13th century (check out references to Al-Jazari’s programmable automaton drum players from 1206 in Turkey), it was the Linn LM1 drum machine from 1980 with its digitally sampled sounds which put an end to the tape loop for music production.

But that is another story…

Simon Edgoose

September 2020