I know I mentioned that we’d look at Velocity Curves this month but having had a think about it, it would make much more sense to look at those interestingly named Thresholds.

Thresholds? Ok, so you’ve probably seen that in your module (although it may be disguised with a different name) but it is actually MUCH more important that most people realise and can get you out of trouble very easily.

So lets think about the word ‘threshold’. The only other time I can think of it being used in a non drum related way is when it comes to doors (and if you remember last months diagrams, you’ll probably realise that there is a repeating theme here). The threshold of a door is the step at the bottom over which you have to er… step. Or if it raining heavily and flooded outside, the bit which the flood water would have to be higher than in order to get inside your lovely house. So, last month we were looking at the top of the door (gain), and this month we are looking at the bottom of the door (threshold).

If you think about it, if you have a high threshold, the water has got to be extra high to start to get in. If you have a low threshold, it will take less time for the water to rise and start to get into your house. Make sense?

If you think about it, if you have a high threshold, the water has got to be extra high to start to get in. If you have a low threshold, it will take less time for the water to rise and start to get into your house. Make sense?

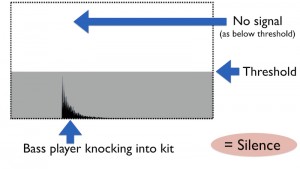

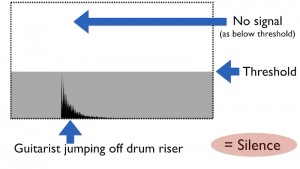

Ok, well just as we don’t like soggy carpets in our houses, we also don’t want accidental hits and vibrations from the bass player to trigger our lovely electronic kit, especially on stage in front of an audience. These ‘mis triggers’ are like the flood water – if the threshold is high enough, they don’t make our carpets soggy/accidentally trigger out ekits when we don’t want them to. If the threshold is set too low, every time the bass player plays a low E very loudly, or brushes your drum rack with his headstock, it will make a pad (or two) fire accidentally, which just like soggy carpets is not a good thing.

But just making sure that out ekit doesn’t make a noise accidentally probably doesn’t seem that important. However, that’s just a by product of having a correctly set threshold.

If you’ve had a look around the inside workings of your module, you’ll probably have come across things called ‘rejection settings’ and ‘cross talk cancellation’ which sound very serious and heavy duty. They are to do with stopping accidental firing and similar problems. If you have ever hit one pad and another pad has made a noise, then that when you normally go hunting for those settings, BUT in my experience, if your threshold setting are correct then all those wonderfully named parameters just aren’t required. In a nutshell, understanding and setting threshold correctly makes for a perfectly performing ekit in 95% of cases, and is MUCH easier to understand and work with.

If you’ve had a look around the inside workings of your module, you’ll probably have come across things called ‘rejection settings’ and ‘cross talk cancellation’ which sound very serious and heavy duty. They are to do with stopping accidental firing and similar problems. If you have ever hit one pad and another pad has made a noise, then that when you normally go hunting for those settings, BUT in my experience, if your threshold setting are correct then all those wonderfully named parameters just aren’t required. In a nutshell, understanding and setting threshold correctly makes for a perfectly performing ekit in 95% of cases, and is MUCH easier to understand and work with.

(The other reason for not using these more fancily named parameters is that they generally slow down your electronic kit. Things like ‘scan time’ require the module to look at that input for as long as you’ve just set it (say 2ms) for it to decide whether the signal is a ‘proper’ hit or not before firing a sound, therefore slowing down the response by 2ms. ‘Cross talk cancellation’ generally requires the module to look at two or more inputs and compare them to see which one came first or which one is bigger. To do this correctly, the module obviously has to wait for all the events to have happened before it can compare. This might only take a few milliseconds but it rather ruins the latency time that the manufacturer boasts about your module(!).)

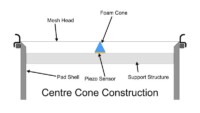

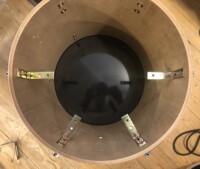

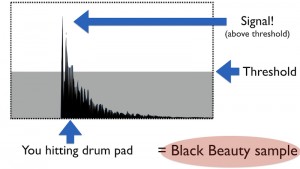

Electronic drum pads are actually their own worst enemy – the very thing that makes them work (the vibration caused by you hitting it with a drumstick) is also the very thing which makes it behave badly (the vibration caused by you bass player knocking into your kit). Both are vibrations, but one is required and one is not. Thankfully (and this makes things much easier) usually the ones you don’t want are much quieter than the ones you do want.

Electronic drum pads are actually their own worst enemy – the very thing that makes them work (the vibration caused by you hitting it with a drumstick) is also the very thing which makes it behave badly (the vibration caused by you bass player knocking into your kit). Both are vibrations, but one is required and one is not. Thankfully (and this makes things much easier) usually the ones you don’t want are much quieter than the ones you do want.

Imagine two drum pads mounted on the same stand. If you hit one, it will make a sound. But because of the nature of physics, vibration from you hitting that pad also goes through the stand and makes the other pad vibrate. If the threshold is not set correctly, the second pad will also trigger a noise (albeit more quietly, assuming your velocity curves are set correctly – see next month!). So this is why we need to set everything up correctly.

So how do we do this? Well, the first thing is to be honest with ourselves. If I asked you to hit a snare pad at the quietest velocity you would hit it on a gig, you’d probably hit it so lightly and delicately that the pad would hardly register. However, lets be realistic here – the quietest we’d probably hit that pad at home or on a gig is actually more like a medium quiet velocity. So if we go to the page in our modules where we set the threshold (‘threshold’ on Roland, Alesis, ddrum and 2box kits, ‘minimum level’ on Yamaha kits) and turn it up slowly until we stop being able to hear our quietest hits, then back it off a little so we can hear them again, then we should have just set that pad correctly.

The important thing to remember is that every pad is different – ever pad is mounted in a slightly different way and that way might change how the vibration gets to it- so each pad needs setting differently to each other. Its worth putting the time in to get this correct.

So, in a nutshell, rather than using the more fancy/clever parameters, simply by setting your gain correctly, setting your thresholds correctly and setting your velocity curves (see next month), you should be able to get rid of 95+% of triggering problems.

So there you have it – the right height threshold stop you getting soggy carpets and misfiring electronic drum pads. Who’da thunk it?

Simon Edgoose

February 2018