Ah, the first of probably a few contentious subjects!

If you are under 40, this may mean nothing to you. If you are over 40, the word ‘sample’ may mean something entirely different…

So, you know that lovely electronic kit you own? How are those sounds made? How do they come to be penetrating your eardrums everytime you hit a pad? How are they squashed into the drum module?

Well, over the next two articles we are going to look at the two main methods for creating those lovely drum sounds that we listen to everyday. I’m going to simplify bits so we don’t get too bogged down in technical detail, and if you dispute what I’m saying, I’ll put some links in to different articles and papers.

So, why is this contentious? Weeeeell… one of the methods is used by 90% of edrum makers, software companies and the like, while the other method… is used by pretty much just one company. And being good business men, everyone likes to think that their method is the best, most accurate method for recreating drum sounds. This has somewhat polarised the market, even though there are quite a few users of modelling, but they use it in addition to sampling, rather than as the main form of sound reproduction (but more of that next time).

I’m not trying to say one way is better than the other, but what I do want to do is explain roughly how each work, and then you can go out, try everything and decide which works for you, and what sounds good for the style of music you play. There is a LOT of wrong information out there so I thought I’d add more wrong information to the pile… only joking!

So, what are these two methods? Well, sampling, and modelling. You’ve probably heard of both, and if you are like 90% of people I talk to, you wont really know the differences. So lets look at each and try and make it as clear as possible.

So, to go back to basics, when you hit a drum pad, the module uses a microprocessor (mini computer) to play back the correct sound for that pad and that hit. But what we are talking about here is how the microprocessor stores or makes the sound that you hear. And that is the main difference here – one method plays back a stored sound, the other method creates the sound you are expecting on demand.

As these are quite long subjects, this time we’ll look at sampling and we’ll look at modelling next time.

Sampling

So sampling is the method we are all most familiar with – we use it everyday in ways we don’t really realise. For instance, when you listened to that track on your phone in the car earlier, that was (to all intents and purposes) a sample. It was a digital recording of the music and it was played back, on demand, when you touched the screen of your phone.

So sampling is the method we are all most familiar with – we use it everyday in ways we don’t really realise. For instance, when you listened to that track on your phone in the car earlier, that was (to all intents and purposes) a sample. It was a digital recording of the music and it was played back, on demand, when you touched the screen of your phone.

This is no different from you hitting a pad (the same as your touching your phone screen) and it playing back a Black Beauty sample (or Justin Beiber’s Greatest Hit in the case of your phone – don’t worry, your secret is safe with me).

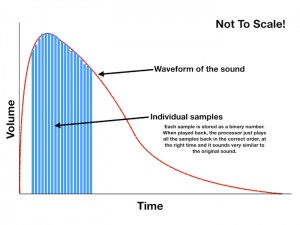

Sampling has been around for years and years (and the first sampled drum machine, the Linn LM-1 was released in 1980) and it hasn’t really changed, except in quality. These day, most samples are what’s called 16 bit, 44.1kHz or 24bit, 96kHz. That means that the computer or sampler that recorded the sound (Justin Beiber or your Black Beauty sample) took 44,100 or 96,000 ‘slices’ of the sound per second and stored the information. Each ‘slice’ says how high the waveform of the music was at that precise point, and by replaying the ‘slices’ back in the correct order, and at the right speed, the waveform of the music can be rebuilt and replayed into your ears.

As those bits are binary (1’s or 0’s) a single ‘slice’ could look like this in the case of a 16bit sample;

1011010001010011

So if you imagine 44,100 times that much information, that is how much data a sampler stores for every second of sound. If you think that is quite mind-blowing, welcome to the club!

(As a bit of a nerd experiment, I just got a program to randomly generate 44,100 pieces of 16bit data and it filled 1193 pages of A4. That is a LOT of data and that is for EVERY SECOND of a recorded sound at high quality! Obviously your phone stores data at a lower quality but thats still a load of data for each Beiber track)

(As a bit of a nerd experiment, I just got a program to randomly generate 44,100 pieces of 16bit data and it filled 1193 pages of A4. That is a LOT of data and that is for EVERY SECOND of a recorded sound at high quality! Obviously your phone stores data at a lower quality but thats still a load of data for each Beiber track)

Plus, the more slices that are taken per second (96,000 rather than 44,100 for instance), means an even more accurate recreation of the sound, but it also needs much more storage space so there is often a compromise.

But more slices per second isn’t necessarily ‘better’, and that depends on what you want to do with the sound. If I want to use a drum loop in a track, I often find that a 16 or 24 bit sample takes up too much ‘sonic space’ if I keep it at high quality, whereas an 8bit or 12 bit sample from a late 80’s drum machine sits in the track much better and is less intrusive into the whole sound.

So, we know that sampling uses a lot of space (which is why it can be expensive as it needs lots of storage), but the clever bit comes when the edrum makers or the sample house (a company who just make samples) put the samples back together again.

To make the sampled sound more realistic, makers use a load of tricks;

-

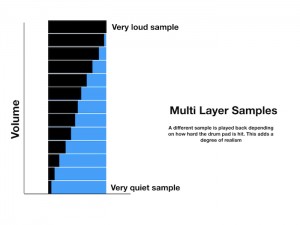

Multi layer samples – rather than just one sample per hit, there may be 100+ samples to cover all the volume levels from the lightest hit, to the loudest hit. This stops the sound being the same regardless of how hard you hit the pad. It adds a degree of realism (after all, a snare doesn’t just sound louder when you hit it harder, it has more harmonics/overtones, more buzz etc)

-

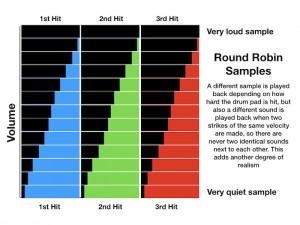

Round Robins – rather than just one sound for each volume layer, there may be multiple sounds for each layer so there is always a new sound being played, even if you play exactly the same volume over and over. If the same sound is played repeatedly, it often results in ‘machine gunning’ where the sound sounds unnatural and stuttering…

-

… so there are often Anti Machine Gunning aids – to further stop the machine gunning, some makers slow the start of the sound to make it smoother, but only when the sound is repeatedly played fast.

So sampling works by playing back many different recorded sounds in a way which to our ears sounds like the original instrument. It is relatively simple but needs a fair bit of storage to hold all the thousands of individual samples, and requires a lot of programming to make it as realistic as possible.

So sampling works by playing back many different recorded sounds in a way which to our ears sounds like the original instrument. It is relatively simple but needs a fair bit of storage to hold all the thousands of individual samples, and requires a lot of programming to make it as realistic as possible.

So that’s sampling in a nutshell (it’s actually quite a bit more involved when you get into the delights of crossfading without phase issues and the like but we’ll forget that for the moment), so thats it for this time. And lets look at modelling next time. If you have any questions, as usual, please get hold of me on simon@edruminfo.com

Simon Edgoose

July 2018