If you’ve been in the lucky position of recording with a band, then you’ll be aware of the expression “It’s being mixed…” often followed by “…we’ll get it back in a week” or some such longish time schedule.

The art of mixing records truly is an art. It’s not easy to take 30, 40, 50 or more tracks and mould them into something which sounds like a hit record (or if not a hit record, at least something to be proud of). It’s no surprise that it takes time.

So I was rather intrigued when I read about a book by a certain Billy Decker. Billy is a record mixer who works mainly in Nashville. What makes Billy stand out from the crowd is the fact that he mixes most of his records in 45 minutes or so. Yes, 45 minutes, not 45 hours, or even 45 days.

Now, when I first read this, I was ready to call BS, but on closer inspection, this is exactly what he does (he even mixed 7 singles in one day apparently). He’s no small time wheeler-dealer either – his mixes have appeared on 50 million albums, and billions (literally) of streams, and he’s mixed 16 Billboard Number 1’s. Check out his AllMusic page here https://www.allmusic.com/artist/billy-decker-mn0002570782

He REALLY knows his stuff.

How does he do this? Well, after years of mixing, he realised that he generally did the same things with the same instruments, so rather than set everything up from scratch at the start of each mix, he created a template which does most of the work for him, and he just drops the tracks into his template and he’s 90%, or more, of the way there. The rest is just small tweaks.

This means that he has set up the EQ, compression and any other effects already, and everything just gels together and gives him a radio ready mix. Easy.

I should point out here that Billy does most of his work in the country music field, which you might think explains how he does it (“We play BOTH types of music here – Country and Western!”), but he’s done more pop chart orientated stuff too. He’s not a ‘one trick pony’.

So what has this to do with edrums?

Well, Billy has a few interesting ideas when it comes to drums. Two which spring to mind are – 1. He NEVER uses the original kick drum that he is supplied with, and 2. He EQ’s the toms the same, regardless of what size they are, how many there are etc. He also uses a LOT of drum replacement software but thats another story… sort of.

Now, I wondered if I could use some of Billy’s ideas for my programming and work on edrums, and I have started to use them, and they work brilliantly, but there’s one I wanted to look at here.

As I mentioned above, Billy doesn’t use the original kick drum on any recordings that he is send to mix. This is because, why spend 45 minutes EQ’ing and tweaking the sound which was supplied so it fits the track, when you can use something else and take 45 seconds?

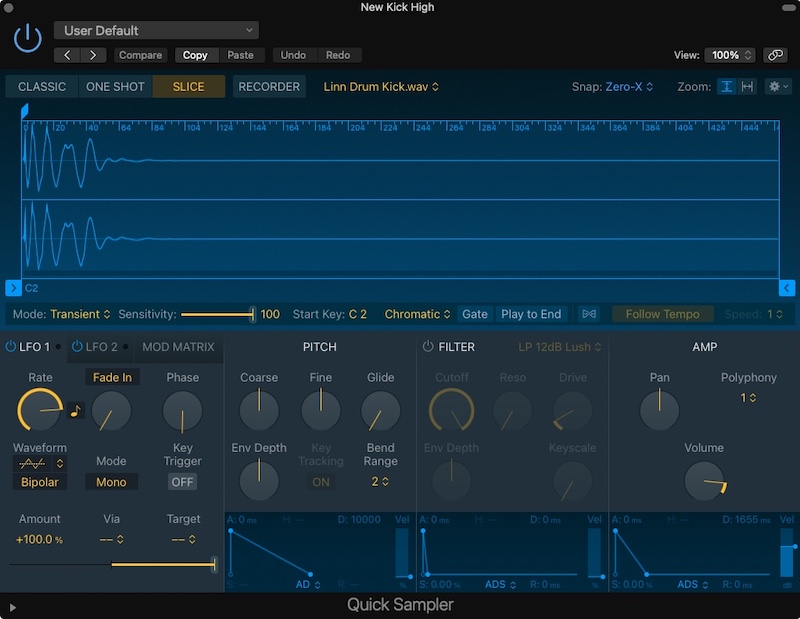

What Billy does is extract the performance from the recording, using drum replacement software, and then trigger three bass drum audio samples all simultaneously. One sample is mostly low end, one is mostly mid range, and one is mostly the high end. Each sound is pre-EQ’d (Billy provides the EQ settings in the book) so they ‘fit’ together.

And simply by adjusting the mix of these three samples, he can come up with a kick sound almost instantly which fits the track, regardless of what the track is.

So I tried it.

And it works… really well.

Obviously I’m simplifying things a bit (and I really recommend any musician to read Billy’s book – Template Mixing and Mastering by Billy Decker and Simon Taylor, available as a book or on Kindle), but it is as simple as that.

Obviously you need to choose your samples really well, and Billy cleverly doesn’t tell you what he uses, or provide examples, so you have to work it out yourself, but as a drummer, if I cant pick three kick samples which work together, then my ears are shot.

(Yes, with an ‘o’…)

I don’t know if I was just lucky, but following Billy instructions, I carefully chose three samples, and just by adjusting the amounts of each one, I can go from an ultra electronic kick, to a dance kick, to a John Bonham kick, just by turning three knobs (virtually or on a USB pad controller).

But what is more impressive is the variation I can dial in – Bonham with a bit more attack, thuddy 1980’s Recording Custom through a D112, hard dance kick which makers the speakers really pop, and so on. It’s brilliant!

The only time I need to make changes to the basic recipe is when I need it to sound like a much smaller bass drum, like an 18” bop kick, and then I just pitch up the lowest sample (which is a ringy, open acoustic kick sound) and it’s done.

I don’t do much mixing – just the tracks I use for demo’s and other things I get send to work on, but this has really helped.

It also means that I will be able to trigger a kick sound live (when the gigs start again) and always be able to dial in the sound so it suits the PA perfectly, without having to let someone else mess about with it.

This book really has been a revelation. If you are at all interested in recorded drum sounds, then I really recommend you check it out.

And this is just the start. You need to also check out his ideas for mixing snares (again using three samples – low, mid and high – but this time blended with the original snare) and the previously mentioned tom EQ setting (again, so simple, but it really works).

This book could make getting your live or recorded drum sound as easy as 1,2,3. I’m not saying you’ll be the next Bob Clearmountain in a week, but it’ll definitely be a start.

Thoroughly recommended.

Simon Edgoose

April 2021