The name Neal Wilkinson certainly doesn’t need much introduction.

The name Neal Wilkinson certainly doesn’t need much introduction.

Known and in-demand for his unique sound, feel and stylistic diversity, he has had a solid place in the UK session scene since the mid 80s, which soon saw him working on both sides of the Atlantic. After a busy few years in Los Angeles, Wilkinson made his way back to England where he got straight back into the local recording scene, West End work and touring with one of his favourite artists, James Morrison.

Over the years Neal has not only played with artists like James Morrison, Paul McCartney, Ray Charles, Mike and the Mechanics, Van Morrison, Annie Lennox, Michael Ball and Leona Lewis (just to name a few), but also worked on TV shows like American Idol, X-Factor, Friends, and recorded drums for countless movie soundtracks.

I caught up with Neal at the Royal College of Music to chat about his upbringing, his time living in America and ‘practising what you already know’.

Your interest in drumming was mainly sparked by your uncle?

Yes. He used to play drums and my mum and dad took me to see one of his gigs when I was around seven years old. Every time we went to see him play he would sit me on his lap for the last tune of the set, put the sticks in my hands, my legs on his legs and we’d play the song together. He was essentially semi-professional but it was at a time when there was so much work around that he didn’t need another job. He had a passion for Big Band music and loved Buddy Rich. I remember him saying that Buddy was probably the greatest player, but his favourite was Sonny Payne who played with Count Basie. Sonny was technically not as good as Buddy Rich but his feel and sound was just something else. That was an important early lesson and still sits with me today. Don’t get me wrong, I love drums – but I love music much more. I could count on one hand the times drums made me emotional and made the hair on the back of my neck stand up. Music, lyrics, harmony and chords does that all the time.

Did you get your first drum kit from your uncle too?

No. When it was obvious that I was interested, my dad got me a little drum set which I just didn’t stop playing. I think it lasted for about a year until I got a better one.

Then, when I was seven, we were on holiday in a resort in Margate and they had a kids talent competition. I had been playing drums for maybe six months and for some reason decided to get up and take part – which was very unlike me as I was a very shy kid. I think I came second and got a little toy gun or something like that. Importantly, there was a guy there who came up to my dad and said “I think your son is good!”. He gave my dad his card, and it turned out to be Chris Hayes, a journalist for the ‘Melody Maker’ which was themusic journal in the UK in the ’60s and ’70s. They used to do all kinds of gig and album reviews, articles and classifieds for musicians, it was thick as a newspaper. My dad gave him a call and Chris said he would pay for me to have six lessons with Max Abrams. Max was the go-to drum teacher back then, so I travelled from Coventry to London for the lessons to see if I was worth teaching. I was only eight at the time but ended up going to Max for lessons for eight years. It was mainly reading and snare drum rudiments in a pipe band context, which really swing, and I think that’s one of the reasons I’ve always had an affinity for Steve Gadd. Hearing him using the stuff I’d been taught was very inspiring, and it all started to make sense. Then, when I was about 15, Max sent my dad a letter explaining he was shaping me to be a studio drummer, and I think it’s incredible that all of this just came form me entering that competition and one stranger seeing something in me. I’m extremely thankful for what Chris and Max did for me.

You start gigging soon after that too, right?

You start gigging soon after that too, right?

Yes, when I was 11 I started playing for the cabaret in my local town twonights a week. At that point I had had lessons for a couple of years and I could read music pretty well. So when singers and magicians would come in and hand me their music, I could play it.

I did that till I finished school at age 16 and then went down the usual path playing for big bands in holiday resorts for a couple of years. That led me onto playing on the Queen Elizabeth II cruise ship where I was the drummer for one of the big bands and ended up doing a world cruise when I was 18. That was amazing. There were a lot of incredible musicians on the ship from London who tried to convince me to move there too. I really didn’t want to move into town though so I ended up coming down from Coventry a couple of days at a time crashing on peoples sofas; and that’s when I gradually started making breaks into the scene.

Getting busier and busier then convinced you to move to London?

Well, yes but my problem was that I came to London when the drum machine came out. I still remember going into studios and seeing my first LinnDrum. I had never heard of that. Then of course all my friends were being called for sessions: bass players, guitarists, keyboard players… not many drummers. It wasn’t the best time to try and break in. The guys who were already established got the work that was there – quite rightly so. But when I was 19, I had an amazing opportunity to play with Dick Morrissey and Jim Mullen (Morrissey Mullen band) which lasted for 10 years. They had covered for Stuff in New York back in the late ’70s when Stuff were in Japan, and brought that R’n’B gospel vibe back to London. I learned so much from playing with those guys, especially about time and groove. Dynamics too.

You were involved in a lot of movie soundtrack recordings as well.

Yeah, quite a few. Let’s see what springs to mind: lots of us were there for the recent Mission Impossible sessions. There were about 14 drummers I think. I also played on the songs they used for the movie. We also did a bongo session, which was hilarious. They said they couldn’t tell us what the movie was but there were the charts – 5/4, bongos, [claps the signature Mission Impossible rhythm]. Hmm… what could that be? For the recording we had 48 pairs of bongos set up in Air studios. Crazy.

I also played on ‘Return of the Jedi’ and actually have a character name in that! I’m the drummer in the Max Rebo band. That was a really tricky session actually. They had recorded everything in L.A. but for some union reason they could only use the orchestral part of it, so we had to re-record the drums. Gregg Bissonette had recorded the original drums and when Jerry Hey came over to produce the session, he handed me a transcription of it. We did some takes and when we listened back to it he had Gregg’s drum part in the right speaker, my part in the left and compared every note. Of course you never gonna get them exactly the same. Even if you did, you could still hear which one was Gregg’s drumming and which one was mine. It’s quite incredible that even with the exact same parts you still get minute differences in dynamic, placement and touch.

It must be a great feeling being part of these iconic movies.

It must be a great feeling being part of these iconic movies.

Yes, but nowadays you’re more detached from it. I do remember my first few movie sessions and some of them were in Abbey Road Studio 1 with the movie on the big screen and the conductor directing us to the timecode. Now everything is synced to click, you’re in a booth recording your parts separate from everyone else.

There is a lot of pressure on these sessions but not like most people would think. Everyone thinks about the pressure of playing odd time signatures or complex and unfamiliar styles. That’s all true but quite often it’s the context that makes parts tricky. Imagine there is a beautiful string intro, 80 musicians have just played their part perfectly, then the click starts and you have to come in with a simple kick, snare, hi hat groove, pianissimo. That can be really hard because it’s so bare, quiet and you still have to manage to lock in with the bass perfectly. This can be really stressful and you just kind of have to trust in the fact that you’ve put in the work. Having said that, some of the charts for Angry Birds 2 were pretty difficult!

You lived in America for quite a while. What made you move there?

My wife is American. We got married in California in ’92, she said goodbye to her family and was all ready to move to England in December ’92. In January ’93 we were back in California because I was rehearsing with Veronique Sanson. I got recommended for the gig but wasn’t quite sure if I wanted to go on tour in France for too long because I was getting more sessions in London. I asked who was in the band and the first name that came up was Leland Sklar, so I said yes immediately. Lee and I ended up touring with Veronique for about 15 years and we became really good friends. He lives in LA so I had that important connection there. And then it was actually Gregg Bissonette who always pushed me to move out there. When our first son was born we went back and forth a lot and finally just decided to make the move more permanently. It was great, I did loads of work over there. For example Gregg couldn’t do the last series of the TV series ‘Friends’, so I played all the little play-on stings for the whole series. That was really fun. We just had bars and chords and tried to come up with different grooves and fills for them.

I also did a few really nice records in LA, went to Nashville with Leland for some work and did a whole season of American Idol with the cream of LA session musicians.

At some point I was here in England for some work and got a call to work with Van Morrison. I remember thinking this could end up being a month’s worth of work but it ended up being almost three years. It was great but it took me out of LA for quite a long time. Then, thegig got strange. For example I had rehearsal with him on the Wednesday, but on the Monday, Tuesday, Friday and Saturday he auditioned eight other drummers! It became awkward and I didn’t want to do it anymore so I ended up leaving. Just after that I started working with James Morrison and that’s been close to 10 years now.

You eventually made your way back to England. Do you look back at the time in L.A. with a sad eye?

Well I always try to stay in the moment and not look back but sometimes I can’t help but wonder if it was the right thing to do. I had a great time out there and got to play some very fun sessions with some great musicians. But hey, my sons were small, I had to look at their life; the Van Morrison gig was on the cards; the American Idol gig was cancelled… so it just seemed like the right time to come back. But I feel so at home there, and in London too.

James Morrison is still your main gig at the moment. How did that come about?

James Morrison is still your main gig at the moment. How did that come about?

When I quit Van Morrison I decided to join my wife and boys who had headed off for a holiday in California. I just thought life is too short and I’d rather be lying on a beach than here in London. It was a weird feeling because we played blues in front of 60,000 people supporting the Rolling Stones, or with Dr. John at the New Orleans Jazz Festival and I remember thinking I would never do that again with anybody like that.

I kept hearing James Morrison and thought, this guy is really good. I actually remember telling my wife that I thought he was the only artist of his generation out there who has something real, that he’d be amazing to work with, but what were the chances of that?

About a month after I came back to London I was in Bush studios marking up parts for a TV show. I stepped outside to have a cup of tea and a keyboard player friend of mine walked past me and went: “Neal, what are you doing here. I thought you live in L.A.”. I said: “No, I’ve been back for a while now. What are you doing here?” – and he says: “We’re auditioning drummers for James Morrison”. You’ve got to be kidding me! He asked if I fancied coming in but I was a bit hesitant as I obviously hadn’t prepared anything. He offered me to come in at the end of the audition so I would have some time to write a chart. So, when my rehearsal was finished, I went in, had a play with the band (James wasn’t there for this) and they called me the next day to offer me the gig.

And you’ve been doing that gig for quite a while now.

Yes, 10 years – with a gap because he took some time off for personal reasons. Also when I had done the gig for about five years the management decided to change the band. They hired a new MD in who wanted to shake things up and get young guys in. And why not? That’s what you do and it’s totally fine. It kind of worked but I think James didn’t like it because they came at it from a very modern pop approach: running backing tracks with all the stems from the album and suddenly the backing track is containing horns, strings, backing vocals, loops, extra keyboards and so on. Once that track starts, you’re going. You can’t divert or open things out. And playing to a click, the rhythmic DNA of the band changes because the rhythmic movement is not the same. Also, everyone has to be on in-ears which is a totally different feel. I wasn’t doing the gig during that time but a couple of the guys in the band were saying there seemed to be a kind of yearn to get back to the old approach. I loved the gig so I told them I was absolutely up for coming back.

There were a couple of shows towards the end of that tour they asked me back for and we did it with a bit of track, kind of like a halfway house. I think that was the key because after that it started to get less and less, to the point where there is now no track, no click, no in-ears and no screens. Just bare bones: Keys, bass, guitar, drums, and two BV’s.

I think James is really into it, because he can let an intro go longer, pull the time back slightly or we could just not play for a minute. Like a gig! It’s incredible, and I love playing with him.

I haven’t seen any bands doing that for quite a while. It seems everybody is on in-ears and a huge percentage of bands play everything to a click.

But I like playing with a click too, and in some situations it’s essential and can be a help, for instance in an orchestral setting with tempo and time changes. On the Michael Ball tour I just finished, everything was to click because there was a lot of track running, but it can feel unnecessary some of the time. Yes, there might have been a string section on the record but do you want it to sound like the record? It’s not the record, it’s a live gig. James doesn’t want it to sound like the record. People have the record at home, so why does the live gig need to sound the same? You don’t suddenly find the audience saying: “Wait a minute, where are the strings?”. They don’t do that, they just enjoy the live experience.

The break in the James Morrison gig opened up a West End door for you though. You played the Carole King musical for a couple of years?

Yes. Again, one thing ends, another thing comes up. I’m quite surprised that young guys now can’t wait to get into the West End. When I was their age that’s what you did when your career was over! I understand that it’s well paid and if you do those gigs it shows that you can handle a certain level of reading so you may get a call for movies. TV shows and movies are the things that are still really well paid. There can be a problem with repetition. I mean it really depends on what it is. With the Carole King show I didn’t have a problem with playing the same show eight times a week. Thankfully the MD was of a similar mind to us thinking that we play songs. Of course I’m gonna play the same parts but we are gonna play the songs slightly different every show. Some nights you can feel the energy on stage being a bit higher so I’m digging in a bit more and might play a tougher fill so it creates more movement. Other nights you keep it down a bit more. It’s not like you’re reading every note.

Whereas I was called for Hamilton and apparently you have to play every note. If you open the hi hat in the wrong place, you’re in trouble. I said I didn’t wanna do it. If you step away from the situation, who decides that it has to be like that, note for note every night? Thankfully on Carole King we didn’t have that so you have a much nicer atmosphere where the songs are being played great and it’s less of a ‘Groundhog Day’ kind of feeling. I understand that I shouldn’t have the ego to wanting to play it my way but those are decisions made by somebody at the top and I don’t understand that.

You did a masterclass with your band earlier today where you talked about ‘approach’. Let’s talk about that.

You did a masterclass with your band earlier today where you talked about ‘approach’. Let’s talk about that.

I actually prefer doing a masterclass rather than a clinic because I don’t really enjoy playing karaoke to track. To do this with a band today was a joy. And having 50 drummers in a room it was quite interesting for them to hear, for example, what Richard Milner (keys) thinks about drummers. Same for bassist Steve Pearce and guitaristMatt White. They all want the same thing from a drummer which maybe not many in the room are aware of. They’re looking at flashy YouTube guys and are blown away by it. I can be up there talking to them till I’m blue in the face about simplicity and how they have to nail that first, but it often seems to go over their head. If you’ve got Steve Pearce up there telling them they’re not gonna get hired unless they get their sh** together, it has much more impact.

So we were talking about sound, note length and placement, the dynamic of a note and all that comes with it. Being the energy and drive in the band. Of course you don’t want to be thinking about that when you’re playing music but it’s good to have an awareness of it. Thinking about the time is important.

I’m kind of an advocate of ‘practise things that you know’. Of course you want to spend time stretching yourself and amassing more knowledge but a lot of my favourite drummers don’t really have a very big vocabulary. James Gadson, Jim Gordon, Jeff Porcaro, John Guerin… their vocabulary and facility is not huge, not the priority. It’s more about the sound, the placement, the flow of time, all the things that you’re not immediately aware of. The sensibility of how to play music and how to be transparent. That’s a much deeper thing than chops and I think it’s the untouchable thing. If you want to learn a lick, you can transcribe it. You can’t write down Jim Gordon’s feel. Benny Benjamin of Motown, Bonham’s groove, Steve Gadd – that’s the stuff I’ve always loved. Gadd even says it himself. Have you ever seen that clinic where he plays for a couple of minutes, then stops and says: “That’s everything I know”. And that’s a guy who is master of all.

So yeah, I’m a big advocate of practising what you can already do. What I mean is to really make something about expressing the music and not just about the drums.

Finally, what’s next?

Recent movies I’ve worked on will be out – Angry Birds 2, Everybody’s Talking About Jamie, Avengers Endgame, Mission Impossible Fallout. Albums from Phil Lanzon of Uriah Heep, Cassidy Janson, Michael Ball, and Michael Ball / Alfie Boe.

Then from July, touring Europe, UK, and Australia and New Zealand with James Morrison.

Thanks a lot for your time Neal!

Interview Tobias Miorin

July 2019

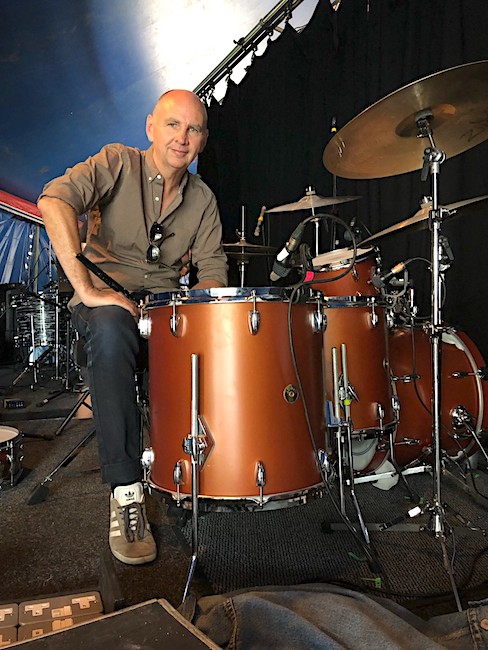

Neal’s gear…

Gretsch drums– Broadkaster in Satin Copper – 20”x14”, 10”x8”, 12”x8”, 14”x14”, 16”x16”

Various snare drums, but usually vintage brass ‘Super Ludwig’ 400/401

Zildjian cymbals – K. Constantinople – 14” hats, 18” crash, 20” HiBell thin, 19” crash ride (with 3 sizzles)

Vic Firth sticks– Steve Gadd signature series

Remo heads– Coated Ambassador on snare, coated Emperor on toms, PS3 on bass drum.

DW pedals and hardware

Protection Racket cases