Big Band drumming is becoming somewhat of a rare art amongst young drummers today, despite the fact that we have all been influenced (to different degrees) by the playing of Buddy Rich and Gene Krupa or learned from the books of Louie Bellson and John Riley.

Big Band drumming is becoming somewhat of a rare art amongst young drummers today, despite the fact that we have all been influenced (to different degrees) by the playing of Buddy Rich and Gene Krupa or learned from the books of Louie Bellson and John Riley.

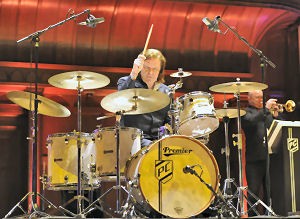

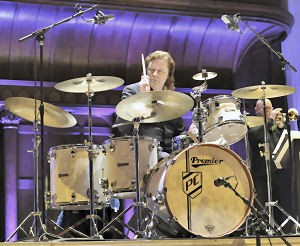

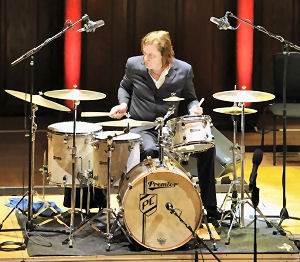

One of the UK drummers keeping the spirit alive is Pete Cater, who as well as being an in-demand jazz and swing drummer and teacher, is best known for his main project ‘The Pete Cater Big Band’.

I caught up with him after his soundcheck for a gig in Soho.

What was your way into the drumming world?

The drums were in the house before I was. My late father was a very good semi-pro drummer and he had this little practise kit at home. By the time I was less than two years old, I had discovered it. I was hearing his records at that time – primarily Joe Morello because the Brubeck Quartet was so massive at that time in the mid 60’s, so he ended up being my first big influence – and that’s what made me want to get serious about learning the instrument. I didn’t hear Buddy Rich until I was five, so he was kind of a later influence.

So the jazz/Big Band influence came from home?

Yes, absolutely. I mean I wasn’t one of these kids that just listened to jazz, I loved all kinds of music: Sinatra, pop music at the time – I was completely immersed in music from an early age. I think it was Morello who inspired me to play drums and Buddy Rich who inspired me to play Big Band music, so that’s why I ended up doing what I do.

Did you have lessons at that early stage?

Did you have lessons at that early stage?

I didn’t really have lessons, I just used to watch my dad practising. He would show me stuff from time to time and when I got a little bit older he’d take me to rehearsals and gigs with the various bands he was playing with, but my thing is being an autodidact [one who is self taught]. I’ve always felt that the things that mean the most in your playing are the things you sit down with and work out from scratch. If you hear a great musician who inspires you, rather than just taking the lick I like to reverse engineer it and find out what it’s based on in terms of rhythmic content, sticking content, orchestration around the drums and then extrapolating. So instead of just taking one lick from somebody, I’ll develop a complete concept based on something that inspired me, as I constantly say to my students, “look beyond the lick”.

Do you think being an autodidact influenced your way of teaching?

Yes. Most of the things that work for me as a teacher are all born of things that started as problem solving for myself. I’m now able to pass them on and see how others are benefiting from it. I currently have a teaching practice based at Bell Percussion in West London and it’s always inspiring to teach fellow pro players who have been in the business a number of years. Understanding that we should all be striving to be better players no matter how big our reputation or profile-that’s really important.

Let’s talk about your Big Band. That’s kind of your baby, right?

Yes! I was in lots of big bands when I was young but heading up a big band of my own was always something I aspire to do from very early on and so I had my first band when I was 19. I found a way of obtaining great big band arrangements from America that weren’t largely available here but I had heard on records. In order to be able to play that music I had to start my own band. There were lots of bands I was in with lots of good players, but there wasn’t the right team all in the same place at the same time who were going to make a good fist of playing the music that I wanted to play back in the early ’80s. That ran for a couple of years back then, but the band that’s 20 years old now, I started a couple of years after I moved to London. I suppose it’s something I’m quite well known for and something that defined my career. It has kind of an identity all of his own, which is exactly what I set out to achieve when we first got started.

You’re describing it as “present day high energy big band jazz”. What makes it present day?

You’re describing it as “present day high energy big band jazz”. What makes it present day?

Well, my ambition originally was for the band to have its own identifiable repertoire and that took me a couple of years to do. Once I had been in London a little while I started discovering guys who are really good arrangers and they were bringing music that they had written. As well as which I collaborated with them, I would sketch out ideas because I don’t have the training to do that myself. I’d sketch out very specific ideas of things I wanted to do and we’d have this exchange of information and ideas and they would eventually come up with the arrangements the way I wanted to hear them.

It’s a very simple formula: as far as repertoire goes, I use standards (the Great American Songbook), jazz classics and original material. With a mixture like that, that’s how I planned the repertoire to work. It would be a great jazz band, but there would be enough about it that had a resonance with a non-specialist listener. I think in large parts with the gigs we’ve done over the years and the records we released we’ve managed to pull that off.

You have recorded three albums so far, any more in the making?

Yeah there is. I want to make the record that Buddy Rich never got round to making. I can’t go into too much detail about that but if he was alive now and had a record deal, what music would he be recording and why would he be doing it? I can see it in front of me and I have a clearly formulated plan but at the moment I’m more interested in doing live shows.

What is your approach to Big Band playing? Do you try to keep it as old school as possible or are you putting your own stamp on it?

I think I have very deep roots as a player. I go back right to the pioneering players like Baby Dodds, Chick Webb, Papa Jo Jones – they all influenced my playing. What I’m trying to do though is take that really old school style and bring it up to date without losing the tradition. I try to incorporate contemporary contexts in terms of what I play and how I play it. I have my roots in the swing era but it’s not like a nostalgic pastiche. For me, it needs to be relevant and contemporary but not losing sight of the tradition. It’s a bit of a balancing act going on but that’s the kind of player I’ve decided to be.

Contemporary as in techniques, vocabulary?

Contemporary as in techniques, vocabulary?

Yeah, all things. If I see a hip young drummer do something that I really like, or if one of my students does something I really like, I’m going to add it to my playing. I’m always looking for new things to say on the instrument.

Do you ever find yourself in conflict between tradition and contemporary?

No, never. The thing is that when it’s time to play music it’s what the musicians you’re on stage with are doing that informs what you do as a drummer.

The most important quality for a drummer is to listen. Once you’re listening to everyone, then you can start to have the right kind of degree of authority in your playing to hold the music in your hands and support it, give the energy when its wanted and maybe back off a little when subtlety is what’s required.

What makes a great big band drummer?

Drama. Light, shade, colour. Being able to go from a roar to a whisper inside eight bars. Listen to Sonny Payne in the late 50s/early 60s Basie band, he was a master of that. He could control that band; take them from fortissimo right down to a whisper in just a four bar break.

How did big band drumming change over the years?

How did big band drumming change over the years?

There’s a timeline. If you want to play this sort of music you got to back to Chick Webb, Gene Krupa and Jo Jones. Then there’s the young stars of the swing era: Buddy Rich, Louie Bellson and all the lesser known guys like Jack Sperling who emerged at that time. Then you have the guys who introduced bebop language into the big band drumming like Charlie Persip, Don Lamond and Dave Tough who was one of the most swinging, hippest big band drummers ever.

Why do you think that genre is a bit rare amongst young drummers today?

I just don’t think they’re hearing it, because as soon as the guys are exposed to the music, they’re fascinated by it. I’ve got so many young guys now wanting to take their first steps swinging with the rhythm section, getting the time centred up on the ride cymbal, instead of the four-on-the-floor and the backbeat, getting that right hand and left foot being the governor of what the time is doing.

But the music is just not in the media. When I was a kid you could put on television and when the bands were over from the states you could see Buddy, Stan Getz, Basie, Ellington, Woody Herman, Maynard Ferguson’s great British band with Randy Jones on drums (really important player who doesn’t get talked about half enough).

It’s just a matter of guys being exposed to the classic master players and wanting to be a part of it. It’s a great privilege for me to be the guy in the UK drum industry who has the profile, and is the torchbearer for this classic style of playing. It’s quite an honour to be afforded the opportunity to share this rich seam of knowledge, be it through live shows, drum industry events or education.

What’s your advice for drummers who want to get into big band drumming?

First things first, book some lessons with me! [laughs]. Joking apart, it’s a really good idea to hook up with a tutor who has the relevant experience and is capable of passing it on. Other than that there are some very good play-along books around. The one that I like to introduce to the guys is a book called ‘Sitting In With The Big Band Vol. 2’, because the charts are sufficiently taxing to be a challenge but they’re sufficiently simple if you just want to sit down and keep time on the hi hat. You can do that and get that together. Then when you want do the fills, the phrasing and the set-ups, you got all the key challenges there to be able to get into that next level. Also, there’s the Gordon Goodwin book, which I know is popular with a lot of people, but if you’re new to the idiom you might want to take a year or two before you get to that because it’s very high standard, pro level material. Probably not the best first step into big band drumming.

Most importantly buy records. Buy old records, buy new records – the wonderful thing now is that virtually the entire jazz back catalogue is available somewhere either on CD’s, vinyl, streaming media, iTunes and so on. When I was a kid you were lucky if you could find certain records. If somebody points you in the right direction as to who to check out and what key recordings to be listening to, there is no reason why you can’t go and seek them out.

What are the key recordings for you?

What are the key recordings for you?

If you want to understand swing, in order to understand the essence of a Big Band swinging, then listen to the Count Basie Band – whether it’s in the 1930s with Jo Jones, the 1950s with Sonny Payne, the 1960s with Harold Jones or the 1970s with Butch Miles – that’s a great place to start out. The music is impeccably played but it’s not heavy or complicated, it’s a great entry point into the genre.

Some jazz artists get derided for playing music that has ‘popular appeal’ and it’s often thought of being slightly simplistic but that music is so important because it’s the gateway. If somebody played me John Coltrane and Elvin Jones when I was a kid it would have gone straight over my head, but the Brubeck Quartet I was able to deal with. So because I got that listening foundation as I got older my taste broadened and got a bit more sophisticated. I was able to embrace other players and more challenging recordings and they didn’t blow all my circuits.

What’s coming up for you this year?

We have the ‘Worlds Greatest Drummer’ show with Steve Gadd joining us on May 26th [the week before this interview went live – a massive success by all accounts], my new small band ‘The Ministry of Jazz’ will be up and running by the end of the year, the first gig is December 14th in Portsmouth as things stand. My teaching at Bell Percussion is very much in demand as I mentioned earlier. I’d like to record a new Big Band album and plenty of gigs. Also I’m back teaching at the Freddie Gee drum camp for the third year running so the future is all looking pretty bright.

Interview Tobias Miorin

June 2015

Photos David McDonald and Paul Rogers