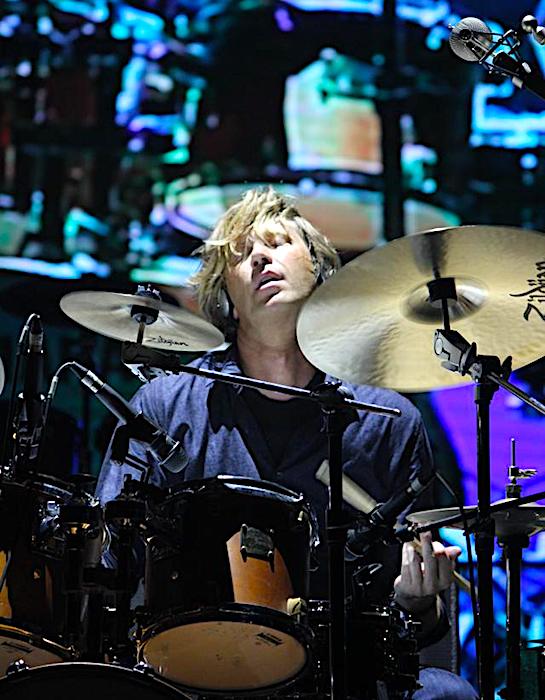

With over half a million distributed copies of his poster ‘Groove Essentials’, Tommy Igoe has made his way onto the walls of thousands of young drummers, music schools and rehearsal studios. The corresponding books and DVD’s have influenced the musical education of pretty much every drummer, and have become somewhat of a ‘bible’ for everybody who takes their studying seriously.

With over half a million distributed copies of his poster ‘Groove Essentials’, Tommy Igoe has made his way onto the walls of thousands of young drummers, music schools and rehearsal studios. The corresponding books and DVD’s have influenced the musical education of pretty much every drummer, and have become somewhat of a ‘bible’ for everybody who takes their studying seriously.

Besides being an in-demand educator, Igoe has a busy session career lending his grooves to multiple shows on Broadway and to artists such as Stanley Jordan, Art Garfunkel, Lauryn Hill and Dave Grusin (to name a few) – live as well as in the studio.

With his recent project ‘Tommy Igoe Groove Conspiracy’ he displays his qualities as a band leader and takes big band drumming to the next level.

I met up with Tommy at the Royal College of Music in London to chat about his musical upbringing, his way into the New York session scene and his involvement in the creation of one of the most successful musicals of all time.

You were born to a drummer dad.

Yes, I took over the family business as I like to say. He was a great drummer and had a great career. He actually won the first ever Gene Krupa contest at the age of 16 and became good friends with Gene. He later got Benny Goodman’s gig at 25 – he was a badass. When he had kids he got off the road and played for the CBS and NBC orchestras in New York. He also became a teaching Guru and that took him to the end of his life.

So there has always been music around the house?

Oh yes. People always ask me: “what’s the best thing I can do for my kid?”, and I always say just surround them with great music. That’s exactly what it was for me. My dad was a jazz guy so I had Art Blakey and Buddy Rich in one ear; and my sisters were the rock’n’rollers, so I had Ringo and Bonham in the other ear. So I’m a real hybrid – a product of my environment. Growing up in New York helped too of course.

I’m guessing it didn’t take long for you to start playing the drums too then?

Well I started grabbing my mother’s knitting needles when I was well under a year old. I would take frying pans and pots out of the cupboard and surround myself with a crazy drum set made of metal and just whack the hell out of them. My dad just went “Oh god, it’s happening”, because he did not want me to become a drummer. He knows what this business is like. Most musicians don’t want their kids to be in this business because they want the best for their kids. My dad wanted me to become a dentist – people will always need their teeth fixed. He was a guy from the Depression Era so he always wanted me to have a safety backup plan. That’s just where he came from. But of course once it became obvious that I was gonna do this, he was very supportive.

You also started taking piano lessons at an early age. Is that a big help in your role as a band leader?

I don’t know how I could lead bands without having deep harmonic and melodic knowledge. You need to be able to speak the language of all the other instruments. When I sit down behind the drum kit, I understand the trials and tribulations of everybody on the band stand. That’s what makes me a good leader. I know what challenges brass players or piano players have. I know what’s happening. If you’re not serious enough about the art form to study it, how much respect do you think you’re gonna get? At some point it’s gonna come back to bite you. Studying the form of the art we call music is extraordinarily easy now. There are more ways than ever to get information. But I think everybody needs a mentor. A guru who has gone through it all before you and can give you insights. I think that’s very important.

You come from a drumline background. Is that where the traditional grip comes from?

Yes I do. At school age, 1981/82, I was part of a drum corps called the Bayonne Bridgemen. That changed my life. The kind of playing, the discipline and the thought process behind playing that style was really transformative for me.

Grip wise it had the exact opposite effect though. I grew up playing traditional due to my dad and when I went to drum corps I played tenors, which are played in matched grip. So I had to get that together quickly.

When did you make the decision to make drumming your career?

I’m a naturally curious person and have many interests but there really was no doubt that I was going tobe a musician. The question was if I wanted to go to school to study music because I could already play really well and was out there gigging. I ended up starting a jazz course run by the legendary bassist Rufus Reid at William Patterson University. Rufus was incredible and really changed my life. I was there for a year but when I turned 18, I quit. That was kind of ballsy – I’ve never really thought about it. *laughs*

You quit because you went out on tour, right?

You quit because you went out on tour, right?

Yes, I went out on the road with the Glenn Miller Band, which was terrible. Everything about it was horrible, but it was a wonderful experience. Every 18 year-old should have the experience of going on tour with a terrible band. It paid absolutely terrible and the reason it was full of kids was because we all quit school to do it – and no adult was going to go out and do that job. Actually, there were a couple of adults on there but they were sadly drunks and it was their last resort. That was the make up of the band. But yes, it was terrible in a way that I’m very grateful about. It toughened me up and I would never know something like this existed unless I did it.

This was 1983 and we went behind the iron curtain: East Germany, Poland – all when it was the Soviet Union. Glenn Miller music was incredibly popular there during the war. It was the music of the resistance – I didn’t really realise that. We played in absolutely stuffed packed venues in Poland, about 40 years after the war, and old people in the audience were openly weeping. I couldn’t understand that, I just thought we were playing that badly! <laughs>. At 18 it’s really hard to have the emotional depth to understand that, especially if you haven’t been raised during war times. These people lived through stuff we can’t even imagine and they had to sneak this music into the country and could have been executed if they were caught listening to it. It was the music of hope. I’ll never forget that and it really changed me because I saw what the power of music can mean to an entire generation of human beings.

You came back to New York after that?

Yeah. When I came back to home after that tour I was just another guy in New York. I tried to get back into school (I was only 18 at the time) but they gave me such a hard time that I just decided to do this by myself. I started studying by myself, taking lessons and spend a lot of time at sessions but I was really just another kid trying to make a name for myself. I started to see my competition and those guys were not screwing around.

Around ’83 I saw the best drummer I had ever seen in my life until this point – to this date he’s still one of the most complete drummers at a young age I know. This was the kid everyone was talking about. His name was Dave Weckl. He was playing with Michel Camillo and Anthony Jackson and it was just so ferocious. It was in a place called ‘Mickells’ and I was sitting right next to his drums. I had heard of him, but I had not heard him. There was no YouTube. You had to get off your ass and go to a place to see people play. At this point Dave had only done a few records but he had his stuff on lock down. It really inspired me and I remember thinking: Ok, that’s the bar. That’s really when my competitive nature kicked in.

At the same time I joined a wedding band. I mean, nobody wants to play weddings but we were all kids and you can make good money doing it. Also, I think I met more great musicians on weddings than anywhere else. It’s all about networking and every interaction you do with other musicians is an audition.

What were your first steps in the New York session scene?

I guess I was 21 when I got my first big session with an orchestra. The session musicians at the time were very territorial, they didn’t like new guys coming in. It was a recording session for a Miller Beer jingle for the Super Bowl. I was recommended for it by a jingle writer I used to record MIDI drums for that he used in his demos. It was just a thing I did and as a result my phone started to ring.

So he called me for this recording and I remember walking in – the orchestra was getting ready and I had to walk through them to the drum booth at the back – and someone shouted at me: “hey, can I get a coffee?”. I looked at him saying: “sure, go ahead” – withoutrealising that he must have thought I was an intern. I was 30 years younger than everybody else in this room. I go into the drum booth to get ready on the kit and people just started turning around looking at me. They were all going: where is Gadd, where is Alan Schwartzberg, where are the usual guys they would normally see on a date like this? I could see them rolling their eyes but that’s a right of passage for kids. They make you prove that you belong and that has a charm to it. You get musical respect after you prove you deserve it.

So I went into my booth and started looking at the music. This was not a groove thing; it was a military-esque piece that went orchestral and it was all written polyphonic over 4 staves, 12 pages long. There was nothing I couldn’t play but it was sight reading and there was a lot going on.

They had a technical problem in the control room so the composer decided to go through every section of the orchestra to listen to their part and make some changes. And by the way, they sounded absolutely amazing! Those were the best guys in New York.

They had a technical problem in the control room so the composer decided to go through every section of the orchestra to listen to their part and make some changes. And by the way, they sounded absolutely amazing! Those were the best guys in New York.

Then the composer says: “drums”, the whole orchestra turned around and I can just feel them looking at me. You know, your career comes down to a moment and I remember thinking: this is it. The first note was a double forte cymbal hit and I hit that so f*** hard. I thought if I’m going down, I’m gonna go down in a fireball. I’ll make sure they remember me. I played it all the way through and I absolutely nailed it. The composer just went: “you missed an 8th note on the end of 3 in bar 4”. And he was right, but before I could say anything he went: “Ladies & Gentlemen, I think we’re gonna be hearing more from Tommy Igoe” and everybody started clapping. Everybody swung back around and I was in the club. That was that. This moment never would have happened if they didn’t have that problem in the control room, I’ll never forget that.

That was my entrance into studio work and because of this date I started to do a lot of session work for the next 5 years. By the time 1990 came along session work was already in its death throes because of technology and drum machines. The decline started at the end of the 80s and it just evaporatedto where we are now.

Over the years you’ve done a lot of work in musical theatre and you wrote the drum set book for the Lion King musical when it first came to broadway. Tell me more about that.

The Lion King drum set creation really happened by accident.

They brought in Julie Taymor to direct the show when they first brought it to New York. She’s a genius and a bit of a visionary, and she decided she did not want any traditional pop – which meant a drum set – but wanted all traditional African percussion. That didn’t work at all, so they got a new musical supervisor in, Mark Mancina, who convinced Taymor to add a drum set.

You have to remember that the music is written by Elton John. He is obviously not an African songwriter. So what they did is take his pop songs and ‘Africanise’ them with the help of South African vocal virtuoso called Lebo M in. He really brought all the beautiful African stuff to the project. If you listen to Elton John’s songs, they really have a pop sensibility with an African flavour.

The musical director was a guy who knew me from doing ‘The Who’s Tommy’ – that’s how I got the job.

Over the years I have subbed on a lot of Broadway shows and subsequently got offered the chair on a lot of shows too but I said no to all of them because I didn’t want to be tied down. So when they first called me for Lion King I said no too. He asked me why and I replied “because it’s gonna suck”. It’s gonna be a bunch of people running around in lion costumes, I don’t want to do that. [laughs]

I personally don’t like traditional Broadway musicals that much but he explained to me that Julie Taymor wants to make it everything but traditional musical theatre and invited me to come in to see the rehearsals. He was very honest to me and told me that they were out of money and couldn’t pay me to write the drum set book but basically that’s why they called me and they promised I could create the book and that’s what happened. It was an incredible experience. The catch was that they needed a 9 week commitment. Every time they try new productions they take them out of New York where there are less eyes watching and the only thing that sold it to me was that they were trialing it in Minneapolis. Just because Minneapolis is a great music town and I was looking forward to spending some time there. That’s where Prince had his club and we hung out there all the time.

So yes, I agreed to go out there and write the book and it all went from there.

And it has been successful ever since.

And it has been successful ever since.

Oh, Lion King will run forever. You and I will be dead and it’ll still be running.

Lion King is a phenomenon. I should have gotten a piece of the writing credits<laughs>, but that’s the thing – we had no idea that we were working on something that would change the rules of Broadway forever. Lion King changed the game in every way – on stage and off stage; musically and financially. Remember this was 1997 and all the incredible rule breaking music theatre productions that have come since have Lion King to thank. The original creative team and musicians and cast was still to this day the most talented group of people I’ve ever been associated with all gathered into one place. But, it wasn’t easy…

I remember once going in to watch one of the tech rehearsals where they adjust all the props and set parts. They were working on the scene where Simba is running from a herd of wildebeests, which is an incredible moment in the show. In the rehearsal they had these wildebeests on rotating barrels at the back. I looked at it and I was so horrified by how bad, amateur and cheap it looked; and I just remember thinking that I made a horrible mistake. I was convinced this show would run a week and go down in a gigantic fireball. It would hurt and my friends will make fun of me but I’ll just make it through these few weeks and after that we’ll never hear of it again. Now apparently there was a special light missing when I watched the rehearsal which tricks your eyes into seeing depths – but all these things got lots of rumours going. People were saying Disney would drop it all and even Michael Eisner, the CEO of Disney, was there in person to get involved.

Our first performance started with the Disney executives coming out on stage saying “the show is not finished, we might have to stop at some point for the safety of our performers”. What a way to start a show. Anyway, we play the first tune, the animals make their way down the aisles, and the moment we hit the last note of the opening tune the place fell apart like we were the Beatles. There was screaming, shrieking and grown men were weeping at the animals. I’ve never heard a sound that emotionally triggered from an audience in my life. That’s whenI realised Julie Taymor is a genius.

It’s funny because up to this moment we had no idea that it was great or magnificent. We didn’t even know if it was good because you can never tell until you play it for other human beings who are receiving it. It’s the same when you make a record or anything artistically. The reason I’m telling you this is because it applies to all artists who are reading this. When you create something you may think it’s good but you don’t know until someone else receives it. They decide, not you.

That was a big moment for me because I really felt the power of original creation.

You have made a big mark on the educational side of the drumming industry as well. Has that side of things always been a passion of yours?

You have made a big mark on the educational side of the drumming industry as well. Has that side of things always been a passion of yours?

Yes. My dad was a natural born educator, I am too. I’ve had very good teachers in my life and I think it’s part of my job to give back what I’ve learned. What good is it if I keep it all to myself and die? So all my books and DVD’s are my contribution to pushing the art of drumming forward.

And they really have become the Bible to many, many drummers…

They have but I really wasn’t planning that. I wrote them as a solution of what I found was a manufactured problem: I think there are authors and people who call themselves educators who have a vested interest in keeping things complicated, because it makes them relevant. I reject that. I believe we play a very simple instrument and the best educators amongst us are going to be the ones who convey information with simplicity, clarity and a minimal amount of ‘blah,blah,blah’.

The first thing I did was a 2 hour DVD with Hudson on the very basics of drumming. Back then drums would be delivered in one box and you had to assemble it yourself; it was like Ikea. When mummy and daddy are a doctor and a lawyer and their son wants a drum kit, they have no idea what to do with that thing. In the video I just explained how it all comes together and what it should look like in the end – and it became extraordinarily popular. Some companies even put it in the box with every drum kit they sold! That was my first introduction to people as an educator. By that time I was already teaching in New York with a two year waiting list.

My friend Rick Drumm at the time was the president at Vic Firth and they had just brought out the very popular 40 Essential Rudiments poster. He called me and said they wanted me to do the drum set equivalent of that. I told him that I was just about to finish writing a book on exactly that. Ding ding ding! I sketched out a poster, they loved it, printed 100,000 of them and it went viral. There are over half a million out there now!

Finally, what’s next?

I live in San Francisco now and I have two spectacular bands that are working and recording regularly. The Groove Conspiracy has a residency at Yoshi’s and we’ve recorded two albums so far with a third on the way later this year. The other band is a killer progressive funk trio called the WIM trio, with Kevin Wong and Ben Misterka. We’ll be playing at the Drumeo festival in 2020 and the release will be out long before then. I’m very excited for both of these amazing bands.

Educationally, Groove Essentials has just been translated into it’s sixth language – Mandarin. I’ve been doing a lot of appearances and tours in China and I’ll be headlining the Drumfest in Beijing in September and then touring the country for the first two weeks of October. I’m also working on a new blockbuster educational venture that will hopefully be finishing in a couple of months. Thats all I can say about that for now!

It may sound like a lot but I am very aware of work/life balance and I prioritize my wife and family over everything else. The happiness in my personal life is what fuels the fire in my music! That leads me to say “no” a lot to offers but saying “no” is so important when structuring a healthy work/life balance. It took me awhile to learn that lesson, like it does for many younger musicians, but I’m glad I now have the ability to see the big picture. I plan on writing a book about this as well.

Thanks a lot for your time Tommy!

Interview by Tobias Miorin

August 2019