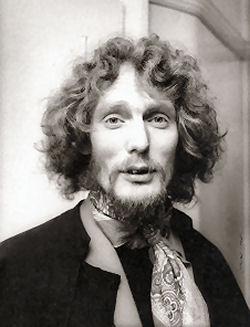

Bob Henritt

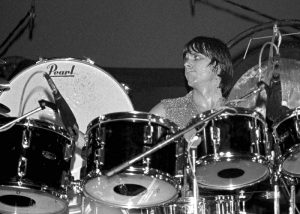

It’s fascinating how some musical partnerships survive the years. Bob Henrit first hooked up with guitarist/songwriter Russ Ballard in the early 1960s as part of The Roulettes, perhaps best known as the backing group for Adam Faith, and in March 2007 they renewed their musical liaison with Ballard’s German tour. As Henrit admits there were “lots of stories”, from their days in the Roulettes, Buster Meikle and The DayBreakers, Unit 4+2, and then Argent, which have inspired him to start writing his autobiography after almost half a century in the music business.

Those decades have seen Henrit at the top of the trade from backing Faith, one of the first British pop superstars to taking up drumming duties for Britpop royalty, The Kinks. Yet things could have been so different for Henrit had fate chosen a different path. His energetic and innovative playing with Argent led Phil Collins to ask him to join Genesis when Peter Gabriel left in 1975. Of course, no-one could have predicted that Genesis would become such a huge international act at that time – the naysayers were predicting their demise with Gabriel’s departure, and besides, Henrit was in Argent and was carving out a second successful career selling drums. Henrit also passed up the opportunity to join John Mayall. But he admits he didn’t really set out to become a drummer. He may even – shock horror – have become a guitarist.

Growing up in the Waltham Cross suburb of north London, he remembers that when skiffle came along “it was a do-it-yourself” sort of music and he just had to get involved. “A friend of mine came along and asked if I wanted to be in his skiffle band. He gave me a washboard and that was it. Of course, the next step up from a washboard was to become a drummer. I sometimes wonder what would have happened if he had given me a guitar.” Safely ensconced into one of the estimated 50,000 skiffle bands that sprang up in Britain in the late 1950s thanks mainly to the efforts of Lonnie Donegan – “I can’t understand why he’s not in the Music Hall of Fame” – Henrit learned the art of drumming (initially with a borrowed kit) and obviously impressed. “I wanted to go for lessons but couldn’t find anybody who could teach me what I wanted to learn,” he remembers. “I didn’t want to play dance music.”

Inspired by The Crickets’ Jerry Allison, Henrit insists the mistakes made by British drummers trying to work out what the American was playing led to a new style of drumming over here. “Jerry Allison could really play. We were trying to work out exactly what he was playing on Peggy Sue. A few years later I played at the Albert Hall with The Crickets (when Buddy was dead) and I watched him play paraddidles on Peggy Sue. We were all getting it wrong.

“I’ve spoken to a few drummers since and I think because we got it wrong, we made our own style. We had taken what we thought Allison was playing and adapted it.” Another revolution was the change from songwriting teams to bands writing their own material, with The Shadows and The Beatles leading the way. “Doing Shadows’ songs was de rigueur,” he admits happily. “I am think I was born at exactly the right time.”

With The Roulettes

With skiffle giving way to rock music, Henrit soon had what he claims wasn’t a difficult decision to make. A boy’s club talent competition in 1959 saw him appearing on television with Cliff Richard – a former neighbour of Henrit’s – and then came the opportunity to join Adam Faith’s Band. “I was still at school when I got the call to join The Roulettes. My parents gave me carte blanche to do it. Where I lived I would have probably gone into insurance or banking in London. Within a very short time my pals who went down that route were doing something different, while I’m still a musician, so my parents were right. I’ve been blessed, but for me drumming, being a musician, was never a licence to print money. I just wanted to play music.” Faith was an all-round entertainer and there was a gruelling schedule for the 16-year-old Henrit. “If you were doing a week in variety you would be away, but if you were in London there might be a radio broadcast in the morning, perhaps television in the afternoon and in the evening a gig. And don’t forget, there weren’t motorways in those days, just the A1 (which ran from London to Crick, near Rugby, until being extended between 1965 and 1968). “We were working all the time.”

Busy times and a few musical chairs saw him in Unit 4+2, playing, along with Ballard, as session musicians on the number one hit Concrete And Clay, before becoming fully fledged members of the band. Then Argent happened. Hold Your Head Up is an instantly recognisable classic from the 1972 long-player Altogether Now with an almost tribal beat between Henrit’s drums and Rodford’s bass. The reality was very much different. Hold Your Head Up was conceived in the Hamburg clubs, where ladies of the night scouted for paying customers and bands played gruelling sets throughout the night as a honeypot for the punters. “We were doing nine 45-minute slots a night,” remembers Henrit. “We had three acts which we just repeated three times. The whole of the bar was too busy, occupied with the girls on the game to take that much notice of us. Nobody really cared what we were playing – except us. “So we would change things around. We’d play the same song but just give it a different beat, a different feel. One time we tried basically a sort of rumba and Hold Your Head Up came out of that. I don’t think anybody realised it was the same song.”

God Gave Rock And Roll To You was the follow up hit – “I still can’t understand why it wasn’t number one in America. I thought it was a great track.” – but to many the wheels came off the Argent bus when Ballard left in 1973 to concentrate on songwriting.

With Phoenix

By this time Henrit’s Drum Store in Wardour Street was enjoying good business, with Henrit reaping the fruits of location. Producers from the nearby record labels or newly signed acts would often come in and buy kits and cymbals, until punk came along. “You’d get drummers who had just signed a record deal coming in and getting the best stuff they could,” remembers Henrit. “We were set up to sell expensive kits. When punk came along, you’d get the drummers coming in, having just signed the same sort of record deal, but asking if we’d got any secondhand cymbals or drums. It was different. “I was in the West End when punk hit. I had plenty of work, although other rock drummers did suffer.”

Different or not, Henrit was called upon to do some session drumming duties with some punk bands and to this day doesn’t know whether his sticksmanship graces any “particularly salubrious” records. Broxbourne-born Henrit is still playing with another of Argent’s alumni, Ballard’s replacement John Verity, with whom he formed Phoenix, along with bassist Jim Rodford following the demise of Argent. And just to keep the Henrit family ties going, he and Rodford joined The Kinks together.

Speaking to Henrit you get the idea that The Kinks’ gig was the most fun he’s had drumming.

Certainly, The Kinks’ To The Bone was a memorable session. And Henrit was an easy choice for the band. He had played on two Dave Davies solo offerings of the early 1980s, before being asked to replace Mick Avory. Recorded in the 1993/4 and released on CD in the UK in 1997, To The Bone was a live recording of the bands most famous numbers, from You Really Got Me, Dedicated Follower Of Fashion, All Day And All Of The Night, Waterloo Sunset and Death Of A Clown recorded at London’s Konk Studios in Hornsey in front of a small crowd, through to gigs at Portsmouth’s Guildhall and the Mann Music Centre in Philadelphia. Henrit had a bass drum, snare, hi-hat and crash/ride for the project which was a stripped down, raw reworking of British musical history. “Ray and Dave (Davies, of The Kink’s) wanted it to be really forceful. They wanted it to rock even if we weren’t playing a particularly hard rocking song. “When I joined in 1984 because of the way Ray works there was a list of songs on the floor of the studio. You couldn’t be drunk. I’d have an inch off the top of a bottle of Heineken and then really concentrate. It was the same live. When we did Lola, halfway through Ray would stop everybody except me. He would sing Lola and then ask everyone in the audience to sing it. There could be 100,000 people all being moved by me, you could actually see them sway along to the drums. “Ray would sometimes go for a middle eight that wasn’t in the song. It was fantastic. Creative tension at its best. You had to be on your mettle. If there’s going to be a train wreck, it’s your job as a drummer to rescue it.”

It’s clear that Henrit has no regrets about his decision to become a professional drummer rather than sell insurance or work in a bank. His joy at linking up with Ballard for the German tour is obvious. “We are such good friends,” he says. “We had some younger guys in the band and they just loved the stories, our memories, of those old days. We had such a lot of fun and that’s when I thought I might as well start writing my autobiography. “You forgot what you’ve done down the years. After one of the concerts in Germany a guy from the crowd came up and said he had a DVD for me and it was of an Argent gig in New York that included a drum solo. I’d forgotten all about it. I look back now and I’m astonished at what I could play.”

Interview by Mark Forster