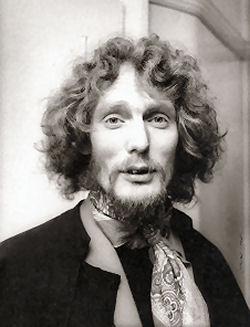

Where do you start with Brian Bennett, a drummer of distinction whose like we’ll probably never see again? He occupies a place in British music history similar to the regard Buddy Rich is held in America – he was an innovator who led the line for others to follow. Bennett the benchmark. And witness his effortless playing on Little B, the song he wrote which perfectly encapsulates his skill as a drummer. Bennett is the man who aspired to be like his American heroes and who arguably surpassed them in style.

Early Years

A teenage prodigy, he was the house drummer at the legendary 2Is Club in London, was one of Marty Wilde’s Wildcats, played with Eddie Cochrane and Gene Vincent before succeeding Tony Meehan in The Shadows. He is a composer in his own right, the proud owner of no less than three Ivor Novello Awards, writing classic tracks for Cliff Richard and The Shadows, including Summer Holiday, as well as a host of film and TV music. His proudest honour was being made an OBE in 2004 for services to music, but he’s got a clutch of other awards. He’s also been a musical director, most notably for Cliff Richard, and a movie star, too, in films like Summer Holiday, where The Shadows’ show-stealing end scene won a standing ovation at the premiere. “We had lines that we had to say but I wasn’t a film star,” he smiles. “I had no intention of being an actor. It was a bit of fun and a very exciting time.”

The Shadows’ brought the curtain down on Summer Holiday in Greek national dress, playing the title track – which brought Bennett his first Ivor Novello Award – on bazoukis and tambourine. “Everybody stood up and applauded that at the premiere. They were great times because we got to go to exotic locations and be film stars, but I was still reading my drumming books on drumming, techniques, harmony. Perhaps best known for his work with The Shadows, Bennett very nearly turned them down. After years of gruelling touring and a married man with the responsibilities that brought, he had hoped to make a living from session work when his wife took a call from Bruce Welch, Shadows’ rhythm guitarist.

And this is where the wheel of fate and fortune took another turn. While he had met The Shadows and Cliff Richard from his days driving the band at the 2i’s, he remembers the first time he met Hank Marvin and Welch. “I was about 15 and was playing Peggy Sue at a gig. At that time I didn’t know Jerry Allison (Cricket’s drummer) was playing paradiddles. I only really found out when I met him years later, but he had this muffled sound. I put a duster over my snare drum and took the snares off to do the number. It sounded pretty good and I remember these two lads from Newcastle came up to me and were interested in how I’d got that sound. It turned out that they were Hank and Bruce. Of course, I couldn’t understand them at the time,” he grins.

While The Shadows are now national treasures, in the early 1960s they were at the cutting edge of British pop music. In fact, many other leading bands yet to come out of maelstrom of skiffle and rock ‘n’ roll, a formative Who among them, began playing Shadows covers. Their influence was huge, but Bennett had already worked with the crème de la crème of modern music in Wilde, Vincent and Cochrane. “Bruce told my wife they wanted me to join The Shadows. There was no audition; I was the number one choice, the only choice. She told him I wasn’t touring any more and he said “We are The Shadows”. “It was just another job to me. Then money came up. I was getting £25 a week, which was a lot of money back then. Bruce said “we’ll double it” with no hesitation.” I asked him when he wanted me to start and he said “tomorrow”.

Tomorrow saw Bennett driving up to Birmingham with Shadows manager Peter Gormley for a TV show appearance and then up to Blackpool for the last two weeks of the summer season. “It was easy,” recalls Bennett. “I just used my ears and had a passion to be good. Tony Meehan was one of the great drummers. He brought a lot to the band and was absolutely perfect for The Shadows. “I liked his work and tried to be true to it, but over a period of time, without anyone noticing, I tactfully brought more of me to the table.”

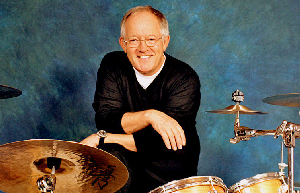

Passion for music and playing in Bennett is evident. You rarely see him without his trademark smile – “I’m happy when I play. If I’m playing well, I’m even happier, and if the kit’s sounding good I’m ever happier, and if the audience likes what I’m playing I’m even happier.”

Passion for music and playing in Bennett is evident. You rarely see him without his trademark smile – “I’m happy when I play. If I’m playing well, I’m even happier, and if the kit’s sounding good I’m ever happier, and if the audience likes what I’m playing I’m even happier.”

It was clear from his days as a child in war-torn London playing upturned biscuit tins for drums that he had a talent and interest in drums. “The first thing you learn to do as a baby is clap your hands,” he says. “It’s natural. When I picked up a pair of sticks it felt like an extension of my arms. “My early recollections are really listening to the radio. I was born in London in 1940 and stayed. I didn’t get evacuated, I stayed put. There used to radio programmes by the Glenn Miller Orchestra from Aoelian Hall, Bond Street. I was caught by it. “It (music) chooses you. It’s a lot like falling in love. There’s nothing you can do about it. Later on my father, when he came out of the Army, would take me to Wood Green Empire. I saw my first orchestra there and didn’t take any notice of anything but the orchestra. It was magical.”

Violin lessons followed for the next year, before he quit – “The violin was very complicated and I wasn’t any good.” – but by this time he had got into the school orchestra at Hazelwood Lane Preparatory School, Palmer’s Green. And thus the hand of fate intervened. “There was a guy who was the drummer and I sat in with him one night. Something happened that lifted the band. It was great. I wanted to do that. He got sacked and I got the job and also his girlfriend. “We used to go to the pictures and see the Glenn Miller Story. It was the first time I had seen Gene Krupa. I went to see that film every afternoon and evening. “Then I joined other dance bands. I was still at school and I remember seeing Lionel Hampton and his band come to Haringay. I was an only child and my parents didn’t really know what was going on with the music scene. I would just disappear on a trolleybus and go up the West End.

“I would go into Doug Dobell’s Jazz Record Shop. You were allowed to take a 78 into a booth and play it. Doug, and those people in the record shops, were effectively your teachers. They would talk to you about music, the latest sounds.”

Brian Bennett

A new friendship turned the teenage Bennett onto the Voice of America radio station in Tangier, which had a jazz hour with the opening theme of Duke Ellington’s Take The A Train, with Louis Bellson playing drums. “That bass drum would make the hairs stand up on the back of my neck,” he recalls.

Bennett became more aware of drummers, mostly American, including Shelley Manne, Buddy Rich, Max Roach and Sonny Payne. A rigged skiffle competition, with Bennett using a washboard sporting photographs of Buddy Rich and Stan Kenton on the back, saw the teenager immerse himself in this new magical world of music, while cherry picking to keep the cashflow situation healthy. “It was a big adventure. I played in jazz bands, dance bands, everything and anything I could. I played with everybody.”

Becoming the house drummer at the 2i’s led him into new opportunities, including the up-and-coming singer Marty Wilde. “I played drums on Teenager In Love,” remembers Bennett. “That was my first recording session, in Phillips’ Studio, Marble Arch. It’s just been released on an album of Marty’s recordings. When I first started drumming with the Wildcats, and through onto The Shadows, we were put on as part of a variety show as a “novelty” act. People thought the new music was going to be short-lived. You had to be an all-rounder.” With Wilde going into movies and the West End as part of his ‘all-round’ duties, Bennett was paired with new acts, including Eddie Cochrane and Gene Vincent. “That was very exciting. In those days you couldn’t get blue jeans. America was the big thing. Eddie had just been in the film, The Girl Can’t Help It with Jayne Mansfield, and was a great drummer himself. He taught me a lot. He played the drums on some of his records. They used another way of doing things. It wasn’t guesswork anymore, we were with the guys who had done it.”

The American influence continued with US import Bruce Gayler teaching Bennett “proper technique”. “Technique comes first,” stresses Bennett. “A drummers’ job first of all is to keep good time and then to swing. You’ve got to make the music live and breathe. “There are a lot of brilliant young drummers today, with a million drums and going at a million miles an hour. It’s mind-boggling and extremely impressive to watch. But they can’t get a groove. Being a drummer today is totally different to what it used to be. “If you can imagine Ringo playing with Cream, or Ginger playing with The Beatles, it just wouldn’t work. Ringo was such a brilliant player. His timing, his feel – he made those songs happen. But Ginger did the same job for Cream. He played what the music required.”

Brian Bennett

While Bennett’s first love is music, he also indulged in his second – the screen. “I’ve always adored going to the pictures – The Silver Screen. It suddenly dawns on you that the biggest part of the movie was the score. It accentuated the love scenes, or the action. It always gave the film some kind of meaning.” Summer Holiday, written with Bruce Welch, was merely dipping his toe in the water of movie and TV music. He started writing ‘accidental music’ – the backdrop to film and TV shows – for the Sweeney, linking up with Dennis Waterman for the first time. Two albums with Waterman followed and the pairing is back together for New Tricks, with Bennett busy on a new series of the detective drama. Something about detective shows must have been in Bennett’s blood, for his second Ivor Novello Award came for his score for the Ruth Rendell Mysteries.

He’s also done Murder In Mind, Pulaski and The Knock. Attention to detail, an enthusiasm to be the best and keep on learning and a keen understanding of what producers are after has made Bennett sought after in the competitive world of theme music.

His approach mirrors that to drumming. “There are plenty of composers and orchestrators who are much cleverer than I am,” he acknowledges. “But my job is to make the pictures look great, enhance them, not detract. You’ve got to strive for another level but not allow the music to get in the way. It’s exactly like drumming. “I try and work closely with the producers, understand what they want, understand the characters, the plot. I’ve been lucky to work with the same directors over a period of time. You both get to understand and trust the language of the other.”

The third Ivor Novello Award came to Bennett for 25 years’ service to the music industry. He recently celebrated 50 years in the business and was presented with a one-off inscribed snare. So, what can we expect from Bennett next? After all this is a craftsman who was at the top of his game with The Shadows when he took a postal course with Berklee School of Music, who always thought he could be better than he was and enjoyed a zest for learning. “I thought I was just happy to sit and play in some room, but I’ve got much better to come. I’m a much better drummer because I’m more daring. I’m not taking any chances, but I’m not really worried about what people think of me. That fear can take away a lot of the creativity. It’s the wrong type of nervous energy. “When we were young there was the big band, the jazz era, dance bands. There was no rock music. We were right on the edge of big band and the front end of rock ‘n’ roll. We bought a lot of technique and feel of big band drumming to bebop drumming. It was innovative because we brought the old stuff with us, but embraced the new. We never stopped learning or adapting, whilst remaining true to the music. It never stops.”

As for a Shadows’ reunion? Never say never.

Interview: Mark Forster