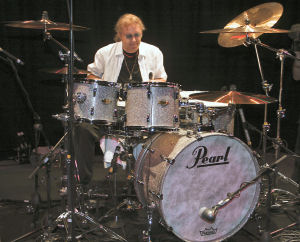

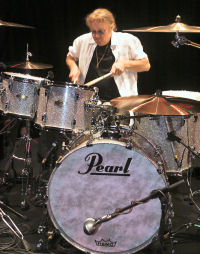

Ian Paice

Ian Paice needs no introduction. He is the powerhouse that has for 40 years propelled Deep Purple with a deep sense of groove, power, swing and swagger. He remains the only man to have played in all the line ups since the bands inception. He spawned a whole generation of rock drummers with his speed, control and knowing when to leave space. His career has also taken in the multi platinum Whitesnake outfit and funky offshoots such as Paice Ashton Lord. He continues to mesmerise audiences – but it is his lengthy recording legacy that is astonishing.

I met him at the Pearl Drum Day 2008 in Nottingham.

Can I start off taking you back to the 70s?

If I can remember that far back, yes.

One of the things I want to ask is how you think recorded drumming has changed in terms of your approach from the 70’s to when you are recording an album now?

A lot of the art needed to record now has been taken away. With the advent of Pro Tools and other programmes like Beat Detective everyone is now the best timekeeper in the world and everybody’s notes are very even and it’s so hard to tell from a record who the really good players are.

The freedom we had in the 60s and 70s has been taken away from us largely by the advent of the click track. With the click track it has wonderful positives and terrible negatives. The positives are that you can replace any part you want very easily and if there’s something you can’t get you can keep going over and over until you get it right. What you don’t get is the drummer attempting something so ridiculously off the wall which is just for that moment in time, and every now and again it’s just right for the record. Where you could let your imagination fly before and if it went slightly out of time, it didn’t matter because the whole band went out of time with you so the apparent effect was that it didn’t go out of time. Of course if you make the slightest little infringement against the click it’s horribly noticeable, so that’s the major difference when it comes to recording. The drummer has very little freedom compared to the past.

The other thing is that people are getting very standardised in the sound that they are allowed to produce in the studio. Producers know that there is a certain sound you can get very easily and very quickly and that’s what they want you to go for. Again you have the same problem where the individuality has been taken out of it; it’s very hard to tell who’s playing anymore. To go back to one of the simplest examples, when Bonzo was playing you knew it was him, it was his sound, when Mitch Mitchell was playing, you knew it was him, it was his style, when Ginger Baker was playing, you knew it was Ginger because it was him. The standardisation of everything is making us lose our humanity and what makes those old records still interesting to kids today who weren’t even born when they were made, is that they have a human connection with the musician creating it. That’s all been taken away by the technologically perfect medium with which we are asked to create art now, the records are now perfect and they’re not as good.

Could you say something about the kind of emphasis on the drum kit? In the last 10/15 years there’s been an apparent shift to the bottom part of the kit, a lot of emphasis on double pedal playing.

Well two bass drums is an amazing effect, but that’s all it is. If you overplay it loses its effect, like a Ferrari and you go everywhere at 180 mph. That starts to become a little less interesting than you think its going to be, but if you go along at 30 mph for a couple of hours and then you do 180 mph then that’s sort of exciting and it’s the same thing with two bass drums. If they come from nowhere, they are shattering but when you hear them every two minutes, the effect is lost. Some of the really good players understand this and they use them when they need them, the same way as the tom-tom or the cow bell, you use it for the moment. Lots of young kids get carried away with the pure thunder of it and in the end there are no patterns.

If you go back to music in the 30s and 40s there were very few patterns, it was a basic time keeper, you were playing 4/4 and it used to go one, two, three, four, one, two, three, four, that’s what it did. When Be -Bop started happening in the late 40s and 50s to rock and roll, we started getting bass drum pedals which was a wonderful shift, before that it was just time keeper or the odd accent. Those sort of patterns are really great because they’ll lead on to other things, they can lead on to bass riffs, they can lead on to guitar riffs, they can create a whole different feel, if you start filling in all the holes because you’ve got two kicks. It can get rather boring.

Ian Paice

Just leading on from that, there’s a whole industry now of what may be termed extreme drumming, I’m sure you’re familiar with the DVD’s. I just wonder about that, what has been called Drumming Olympics.

You have some incredible technicians out there whose business it is to impart this information to the next generation of drummers, that’s what they do. They don’t play with bands, they don’t create music per se, they sell drums, they sell the idea of drumming, and to do this you need phenomenal technique and you need to have different gimmicks. If that’s what rocks your boat, that’s great.

Technique is a wonderful thing to have. Steve Morse the guitarist has a wonderful analogy for it; it’s like having a toolbox with all the tools you need in it, and the more tools you’ve got the easier it is to do the job, but if you don’t have a blueprint in front of you then the tools will do nothing. At the end of the day the instrument is your brain, not how quick you can move your hands and feet and how many rudiments you know. Basically can you create some music?

That technical side of drumming has never been of any interest to me at all. I’ve taken the technique I have, the things I need to use, and you see some of these kids doing this extreme fantastic stuff, to me its like an exercise, I don’t see a lot of music in it. It’s purely for a very small part of the population.

Just one more question from the 70s – The California Jam. I know there was some drama over a double headline with Emerson Lake & Palmer and Deep Purple – I wonder whether you can recall that?

It wasn’t a double headliner, it was Purple and Emerson Lake Palmer, the Eagles, Earth, Wind and Fire, it was huge, we decided we didn’t want to go on last because the day was really long and we know how people get tired, it was also bloody cold. So we decided at the moment we signed the contract we would be the first band on as the sun goes down. Once we’ve done our bit that’s it. It just so happened that Emerson, Lake & Palmer got hit with the last slot and it was bloody freezing. The fracas came about because unlike every other festival, it ran early. So we had 300 odd thousand people there waiting for us and Ritchie quite rightly said “no, we can’t do it, we don’t go on til dusk” and the sheriff was going “no, you go on now or we’ll have you arrested”, and we said “no we’re not going on, and if you arrest us we can’t go on at all” so an abeyance went on and we knew when we came off stage they would try and arrest him so when we saw the sun going down, the lights started to dim, we went on, did the show, and then we had to smuggle him out of the county.

It was a great show; the shame was it was so cold. But I tell you what, I’d love to be 21 again, who wouldn’t, but I wouldn’t want to be 21 now as opposed to 21 then. I was a fairly good looking young kid, I had more money than I knew what to do with, I was a rock and roll star in the 70s, it doesn’t get any better than that

Ian Paice

In terms of technique, you’re well known for a very fast even single stroke roll and doubles as well, how do you keep that up over the years?

I think every player has things they find easier than other things. I’ve always found doubles very simple, and that means both speed and power, singles almost as simple. The singles the most basic thing in the world, the hard thing with singles is when you’re getting up to a good speed is to keep the evenness of the hands, your weak hand always wants to start doing something different whether it gets tired or just slightly out of synch. That’s just practice. I don’t mean to practice for hours at a time, it’s a matter of just keeping the muscles remembering what they’re meant to do, and it might be two or three minutes a day. At the end of the day the real speed starts with your fingers, it’s a matter of just getting the muscles in balance, so singles and doubles I’ve never really found difficult. I find flams a little more demanding, I play them but I’m sure I don’t play they correctly, but it’s sort of worked OK for me.

Do you do any teaching?

No, because I don’t know anything about it (technique). As ridiculous as that sounds, it really isn’t. I never had time to learn what it was I was doing. I got my first kit at 15, I’d been bashing around on furniture at home for a couple of years and I made a snare drum out of biscuit tins. I joined a local band, and at 17 I was asked to join another band that was professional. At 19 I was in Deep Purple. So for me it went from being an absolute novice at 15 to 19 and a bit being able to record with a pretty shit-hot band and hold my end up and that was only possible through the ability to play gigs all the time. As a 15 year old I would be doing 3 sometimes 4 shows a week, as a 17 year old when I turned pro 6/7 shows a week, no breaks. But that meant after a few years you’d done a few hundred shows and if you had the talent, let’s not forget that, you had the experience there to make it work and you learnt so quickly, not just what worked, but what didn’t work. You kept adding to your arsenal of tricks, little things you need to link together, in a way that kids today can’t do. They don’t play enough shows quick enough to get as good as we were in a musical situation playing with other musicians, because they don’t play, they cannot do it, the gigs aren’t there. So it’s much more difficult now for them than it was for us.

Ian Paice

During the 80s there was Whitesnake, how did that come about?

John (Lord) had already been involved in the band and the original drummer decided he wasn’t going to be in it anymore, and I was about the only guy sitting around doing nothing, so I suppose I got the call. With Whitesnake I had a couple of great years, great fun, but financially a disaster, for everybody, not the managers, they did quite well out of it. Apparently the musicians involved never quite realised what they were promised, anyway that’s by the by. I had a great time doing it and again every time you play with someone different you learn something and on that note it was invaluable. I can get real nit picky but my overall memories of it are very good.

Are there people you’d like to play with?

I had the pleasure of playing with one last week. I was depping at a little one day festival in Germany the premise of which was they’d done some super selecting of local bands and then had four or five bands. They were really good amateur players and then the promoters got some really good professional players in to mix and match So you’ve got three guys from Toto, myself, one of the guys from The Scorpions, a couple of guys who were loud enough to make it worthwhile and Leland Sklar the bass player. I’ve know about him for years. Roger and I were big fans when the first James Taylor stuff came out, he was there playing bass and I’d only ever seen him play once before in 1974. I was living over in LA playing in a band I told him this and we had a nice little chat, and then we played together.

Ian Paice

With a day like today (Pearl Day 2008), do you feel pressure because most people here are drummers and they are scrutinising technique? How do you approach it?

I don’t try and do things that are beyond me. I don’t watch other people. I know my limitations and I know what people want from me and I’ve got to go on as confident as I can be and basically entertain them. I don’t need to go on with any sort of apprehension that maybe I’m not going to play as well as the guy before me, that’s totally unimportant. The guy before me could be a genius but he’s not Ian Paice and its people’s memories of the last 40 years of music, some of which has been very successful, some of which has been very good, so all I’ve got to do is go and be that guy and do what I can for them.

I read in a Modern Drummer piece stating that the way you play enabled you to play twice as long and with more energy than when you were 20.

By virtue of the fact that the longer you do something the better you should get at it. I look back at the way I used to work in my 20s and it’s very good. But I did waste a lot of energy playing air. Coming to the knowledge that a drum will only give you 100%, the harder you hit it, its not going to get any louder, all you’re going to get is tired. That might be a slight embellishment. I have no problem doing the odd double show once or twice a week whereas back in those days everything got given in a couple of hours and I look back and there was a lot of energy wasted. As I say, you can’t get anymore out of a drum than it will give you.

Do you still really get a buzz from playing drums?

For me it’s always been my hobby, it still is. I don’t actually think of myself (I know I am a musician and a pretty good one) but I don’t think of it like that, to me it’s a hobby. I’m very lucky it provides my livelihood but I’m not a fanatic, I’ve been on holiday for the last couple of weeks, I haven’t seen a drum kit for the last three weeks. When you’re in a practise room, you can make mistakes that you can’t on stage and that’s the discipline you cannot practise, you cannot rehearse that. So I can go in my drum room with the best will in the world, and if I’m looking out of the window 5 minutes later I might as well stop. If I’m not concentrating I might as well forget it. To me it’s my hobby and when I lose interest I’ll stop.

Words: Graham Allen

Lead post image by Pearl Drums