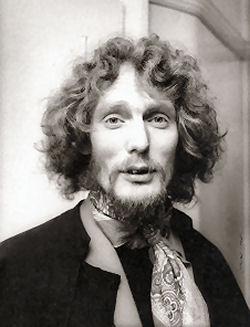

Steve Ferrone

Steve”s tasteful musicality and powerful groove has made him one of the most popular drummers in music today. Steve first came to international prominence while playing with the Average White Band during the 1970s.

I have been a fan of Steve’s drumming for many years and not just because we both come from the same town or follow the same football team. For the past few years Steve has been the heartbeat behind Tom Petty and has also worked with George Benson, Michael Jackson, Eric Clapton and the list just goes on and on.

I caught up with Steve in Austin, Texas to ask him questions in one of the most open and honest interviews I have done.

Your grandma played a big part in your background. Tell us a little more about your upbringing and how you got into drums.

I was brought up in Brighton, the same as you Mike, and played around all the small clubs around town. When I was growing up I went and saw gigs like Jimi Hendrix at Sussex University, and The Who (my band used to open for them in a little club in the Aquarium called Uncle Bonnies Chinese Jazz Club), Freddy and The Dreamers, Manfred Man, Muddy Waters, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee. All these people used to come to Brighton and play and I’d go down and see that it was so cool and it was a great education. However, its a lot different for kids now, to get inspired to play than it was for me growing up.

The other day I was at The Experience in Seattle. Paul Allen (one of the Microsoft guys) has built it and its a massive homage to Jimi Hendrix. You walk in there and there are all these films of people playing, then there’s a virtual room you can go in and learn how to play the bass, guitar and drums -you sit in these little booths and just play. Then they’ve got a recording studio in there and people can go in and bash around and simulate a studio, they don’t record anything but they go and bash around. It’s sort of educational, I found it a little bit cheesy because it’s kind of like Disney World but there’s a lot of kids that go there and look at it and play – there’s a lot of great things for young kids to be drawn to. I was invited by Fred and Diana Gretsch to go up there and share my experience with these kids, I didn’t have to play anything, just walk in and talk about how I started playing.

Things have changed since I started playing. I learnt by watching, the first time I saw how a drummer played I was 5 years old doing a summer show with Max Bygraves at the Hippodrome in Brighton. I looked down into the orchestra pit, we were doing this twist number, and I saw this drummer and I thought ‘look how he’s doing that with one hand and that with the other, I’ll have a go at that’, so I went upstairs and tried to do it and every night I would go downstairs and look at how he was doing it and then go back upstairs and try and do it.

Steve Ferrone

Did you put records on?

Not really, I used to go dancing and I used to practise clapping my hands or playing with a knife and fork, I knew how to make that rhythm. I really believe I didn’t have to work too hard to play the drums but I think basically I had a thing called talent, a gift if you will. It was something I didn’t do anything about but I just happened to be given it when I was born, so it wasn’t that hard. Rhythm I understood because I tap danced since I was 3, as soon as I could walk my mother and grandmother started me tap dancing. I understood rhythm and through tap dancing I got a knowledge of songs, how they work, how it is built rhythmically and once I saw how the drummer played, getting the motor skills, going to add the foot and I could hear what was being done.

And I’m guessing the independence you had from tap dancing?

Well yeah, the hardest thing was to figure out how to bring those two hands down at the same time. One of the songs I learnt was Take Five. I heard that being played and thought ‘that’s a good drum beat; let’s see if I can do that’. I knew how the drums were played then. Then it was a question of adding feet.

What advice would you give to kids now?

It’s all well and good having this amazing technique that some of these guys have got nowadays and they play all this stuff constantly, but it doesn’t really have anything to do with playing the song. I’ve yet to hear a song where that kind of busy-ness says something.

I won’t say who it was because then I would have singled out somebody, but I worked with an artist the other day. I’m one of those guys who I call a studio musician, if I want to define myself, who people can call up if they’re in a pinch. So this artist that I know called me up and said that they were having trouble with their drummer and that they couldn’t look at him anymore. They really needed me to come and do a gig the next day, to play a whole show. A studio musician is quick, he knows how to figure out what needs to be played, what doesn’t need to be played, and what he can’t figure out he can feel his way through. So I got called to do this thing and they sent me the files over the internet of the show that was recorded, the live show, and I listened to it and it was one of these drummers that every chance they got they would play like an extreme fill, it would be like this clatter, and in the end it would take away from the song, it wouldn’t give anything to the song. Every time there was a hole it would get filled with this clatter and I don’t do that.

I had to think like a studio musician being called in to fill this void – is the artist used to hearing that? Is the artist getting something from that? And I thought I’m not going to play like that, I’m going to do my thing and play what I play. I had twelve songs written out and put it in a folder, packed my bag, got on a plane, flew off, got to the place, met the musical director and we sat down and went over certain bits I was unsure of or what I needed to know that I couldn’t tell just listening to the tape. Then went and played the show top to bottom.

Steve Ferrone

The most difficult bit about that was keeping one eye on the chart and one eye on the artist, because if the artist wants something a little bit slower or faster, so you’ve got to have your radar going. I did a few shows with them, maybe three, and about a week later I got a call from the artist and we went out for dinner in Los Angeles and I was told by the artist that they’d listened to the recording of the first show we did and they hadn’t sung like that in years – ‘I don’t know what you did but I just had so much freedom to sing’. I had managed to give that artist enough space to really perform.

Just me saying it isn’t going to convince anybody who’s really into that style of drumming not to do it or to figure out a way around it, but I guess they’ll just find out for themselves after a while that that style gets old, it got old just listening to it and having to go back and try and figure out what was that noise.

So when you’re in the studio and let’s say you’re doing a Tom Petty song, you hear the song and you’re playing a groove, what’s going on in your head, are you singing phrases around it?

Steve Ferrone

There’s usually something I’ll hang on to, whether it’s a riff or lyric, I don’t really think that much, its more a feel, how’s this song feeling. Tom Petty aside because mostly what we do is sit down and play together, you instantly know what’s going on, this feels right, its easy.

When you do things like in my studio, people send me stuff and they’ll send me a track that’s done to a click track and I have to add drums to it. So I’ll sit there, listen to it, write out my chart and I’ll sit down and start to play. Sometimes I’ll know immediately if something’s wrong and other times I’ll be playing, it’ll feel okay but I’ll check it. There’s just something that doesn’t feel that right about it. Sometimes I’ll play the whole thing, think it’s great and then go and listen to it back and think ‘that’s not right’. It’ll line up because when they play with the click they’re playing to that click and maybe they’re just a touch behind, or in front of it and they’ll line it up and it sounds fine. It lines up with the click but when you play the drums to it sounds lazy or too fast, the groove’s not there, so I’ll advance the click 3-9 milliseconds, until it just lines up just right. It makes the world of difference, makes the groove.

If you had to give me four of your proudest recordings, what would they be and why?

First there was an album I did with AWB, Feel No Fret, and the title track of that I thought was really good, I really liked it. We went down to the Bahamas and started recording there and started listening a lot to Bob Marley, so we started to try and somehow find a bridge between what we were doing and reggae. It’s funny because the Police found it, they came along with their stuff, but it was extremely encouraging. When we gave it to the record company they didn’t know what to do with it, then the Police came along with their stuff and ‘thank god somebody did it and did it well’.

Steve Ferrone

Second was a Chaka Khan track called ‘Papillion’ that has such a great groove to it, I really like that song.

Third, I did an album with Pat Metheny called ‘Secret Story’ that was a fantastic album, one of the most beautiful albums I played on I think.

Fourth, ‘Wake Up Time’ on Wildflowers by Tom Petty because what happened with that was we got to the end of the second round of recordings [Wildflowers was done in two blocks of recordings, one in October 1992 and then the next one was maybe June/July 1993], we were right at the end of this recording and I had a flight booked to go back to New York where I was living at the time. Tom had this song ‘Wake Up Time’ and he was going to play the piano and he said ‘Would you just tap the hi-hat to keep me in time’, so I got in there and I’m tapping the hi-hat but there was a looseness to his playing that was endearing, so I kind of followed him, I could feel where he was going, so I played along with his feel, instead of sitting there ignoring it and playing like a metronome. I kept time around his feel for the song, so the song had a breath to it. It was getting near time for me to shoot off to the airport, so we went in and listened to it and it was just beautiful and Tom asked ‘If you were going to play drums what would you play on there?’ and I said ‘Do you want me to do a pass’ and he said ‘Yeah’, so I went in and did one pass and said ‘I’ve really got to go. I’ll tell you what, I’ll go back to New York and fly out next week and finish it off’, he said ‘No, its great’ and the next thing I know the album came out and there it was. It’s there if you listen to it with the dips but it just feels wonderful.

Steve Ferrone

Your CV is incredible, but who haven’t you worked with that you would have liked to, maybe they’re not even here anymore?

When I first came over I sat in once with Herby Hancock. I would like to do some stuff with him. McCoy Tyner, I got to play with him once too, I can’t say I haven’t played with him, I did a show in New York and McCoy came and played. This was a benefit we did, that was a lot of fun. I don’t really know.

Would you go back out and work with Eric Clapton?

I had a great time playing with Eric, I stopped playing with Eric when I stopped having a great time. The fun went out, I think we had played together for nearly 10 years from the album he did with Phil Collins all the way through to Unplugged which was the last thing I did with him. Eric gets tired of his bands after a while. I saw him some years after and he said he’d been listening to a DVD from the Montreaux Festival we’d played at, he said ‘I watched it, you know, we were really good’ and I said ‘You didn’t know it then?’ That band was the greatest band. I’ve been really fortunate that the bands I’ve worked with have been really exceptional bands. Average White Band, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Eric Clapton, were probably the bands that I worked with for extended periods of time and when we used to walk out on stage we were the best band on the planet, everyone knew that, you could count on everybody in the band, you knew that everyone was there for the single purpose that this band was going to sound great tonight. We were going to get out there and when we were finished with the audience they were going to go home knowing that they’d been to a concert.

Who are your favourite bass players?

I’ve been really fortunate to work with some of the greatest bass players. Marcus Miller, Will Lee, Anthony Jackson, come right off the top of my head, Nathan East, Abe Laboriel, Lincoln Goines, Pino Palladino, Dave Santos, Jaco Pastorius, Steve Rodby. All wonderful players.

It’s interesting you say that you are a session musician. Does personality come into it?

I think so, attitude helps a lot. I’ve not always had a great attitude about things, but learned from experience how to not let ego get in the way. But then again who doesn’t have that problem sometimes.

When you’re booked for a session do they book you knowing what you can do and say ‘We want you to do this’ or do you go in and fill someone else’s shoes?

I go to a session trying to figure out what it is they want. I don’t just give them what they want; I try to add something of myself to it as well. I did a session the other day with Ron Blair the bass player with The Heartbreakers. I go down to his house every once in a while and he has something for me to play on, I went down there and he had this thing that had this little groove, it was kind of like a James Brown groove. He cut it to that groove and I played it, it didn’t take long once I knew that was what he was looking for. He said it was great but I listened to it and said ‘You know, can I do one the way I want to do that?’ and it was a whole different thing and he was like ‘Wow, I never thought of it like that’. When I went back this week, to just hang out, he said listen to it, and he put out the one that I did, he just fell in love with it. It doesn’t mean that you stop thinking and become some mindless idiot.

So we called Michael (Jackson)back in and he sat down and we started to play it and he went from just sitting there listening, to dancing around the room and that’s what they used.

With Michael Jackson and Earth Song, Michael wanted that with electronic drums and I said ‘I’ll do a deal with you, I’ll cut it with electronic drums if you let me have a go at it on real drums’ and he said okay. Well it’s called Earth Song, if its an earth song what the hell do you want electronic drums on there for, you want the wood. So off he went and I was there with Bill Botrell a great engineer-producer, we had a great drum sound going, we worked out the part, played it down with the electronic drums and Michael came in and listened to it and said ‘Yeah, that’s great’, so I said ‘Okay, I’m going to put the other drums on now’ and he said ‘Really there’s no need to bother’ and I said ‘Listen we had a deal’. So off he went, he had the whole studio at Westlake, he was very busy, so Bill and I took one pass because we knew what the song was and I went in and listened to it and the real drums just move the air off those big speakers.

So we called Michael back in and he sat down and we started to play it and he went from just sitting there listening, to dancing around the room and that’s what they used. So it is a thing of making the artist happy but sometimes maybe the artist doesn’t know how happy he can be, and to suggest, not on their time, but on your time, let me just have a go and if you like it you’ve got it and if you don’t like it I can leave. Its going to take me one time to do it, it’s not going to take all night. Sometimes they’ll listen to it and say ‘Oh, ok yeah, I see what you’re talking about, but I preferred the other thing’. It’s a creative business and you have to learn to take your knocks.

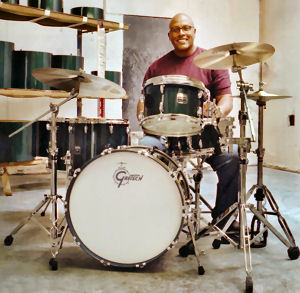

What do you take to a session?

I take everything. I have maybe about 7 or 8 snare drums that I take.

Have you got some vintage stuff in there?

Yeah, I’ve got vintage, new, I’ve got everything. I’ve got an arsenal of snare drums that you wouldn’t believe. If you come out to LA you should come over to my studio at my house and see part of my collection.

What size cymbals do you use, do you like the big hats?

They”re all Sabians. I got 16″ hats and 14″ Rock hats I use as well, I got another set of hats, I think they’re Rock hats but they’re riveted, I use them sometimes. It’s pretty much what things are going to sound like. Most producers are into changing the snare drum or what heads are you using on the toms, put some tape on the toms, or take the tape off, but I’ve never seen one who really listens to the cymbals. Ruben will go through every snare drum you’ve got to find the right one and when we were recording Wildflowers we did ‘Good To Be King’ and I pulled out a Sabian Leopard Ride and put that up and nobody said anything about it and I thought I liked the sound of it and then after the album came out people would book me for a session and say could you bring that ‘Good To Be King’ cymbal because it just spoke so well in the song.

Photo Deborah Arlook

That’s great, I appreciate your time, anything you want to add?

(After a long pause Steve looked at me)

Yeah I have cancer; I got diagnosed with prostate cancer about a month and a half ago now. I’m very fortunate, it was detected early and it was through a test. Actually there had been an indication it was there two years ago and they did a biopsy and there was nothing there and the guy said to me, ‘You’re good for five years’, so this is 2 years later and my accountant said I was changing my life insurance company, so this doctor turns up, takes all this blood, goes away, and I got a phone call from the insurance company saying I had a high PSA, and I said ‘Yeah I had it done 2 years ago and there’s nothing there’, they said ‘Well we want you to do it again’. It’s either that or get a note from the guy who did it before saying its normal for you to have a high PSA. So I called up the doctor and he was on vacation and I couldn’t see him for 5 weeks, so I called my doctor and she said I’ll send you over to see this guy and he said he’d have to do another biopsy, so they did. I’m sitting here and I don’t feel any different, I have zero symptoms, it’s that early. I feel like there’s nothing wrong with me, but there’s this cancer that’s in there. I went to see one of the foremost surgeons in LA.

So I guess if there’s anything I want to say, I know there’s a lot of older drummers around, I did this thing called Woodstick the other day, they had 500/600 drummers all in a gymnasium all playing and it was great. There were a lot of guys there my age and when I talk to them about it, they were saying they hadn’t had their examination yet. So when I do interviews there’s two things I talk about, one is alcoholism – if you’ve got a problem with that, I never tell anybody not to do it or stop doing drugs but I usually say, if you’ve got a problem and you’re in a place where you’re really low, get some help, there’s help out there. So now I have yet another cause, I guess, to tell guys in their 50s, go and get your PSA test and go and get a colonoscopy. I was one of those guys, I was 50 years old, and they were saying ‘Well you have to have a colonoscopy’ and I was like ‘Yeah, I’ll do it tomorrow’.

Footnote: I caught up with Steve 6 weeks later and he had been and had the cancer removed and is now recovering. I wish you all the best Steve and thank you for a very open interview and letting me spend the time with you.

Mike Dolbear