Who put the beat in Johnny Kidd And The Pirates’ groundbreaking Shakin’ All Over back in 1960, or The Walker Brothers’ 1966 classic The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore? What about Tom Jones’ It’s Not Unusual, or Dusty Springfield’s You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me? Not forgetting Englebert Humperdinck’s Release Me, Love Affair’s Everlasting Love, Edison Lighthouse’s Love Grows (Where My Rosemary Goes) and Two Little Boys by Rolf Harris. The list seems endless. Classic songs that have proved a soundtrack to many lives. The answer, probably best known by drummers or music trivia enthusiasts, is one man. Clemente Anselmo Cattini, who has played on nearly 50 British number ones – a record, if you pardon the pun.

He is modestly indifferent about his claim to fame. “The life of a session drummer was who’s this Clem Cattini? Where’s Clem Cattini? I want Clem Cattini, I need Clem Cattini; who’s Clem Cattini?” he laughs. “I wasn’t a particularly proficient technical drummer. In fact, I’ve always considered myself a musical navvie.”

He is modestly indifferent about his claim to fame. “The life of a session drummer was who’s this Clem Cattini? Where’s Clem Cattini? I want Clem Cattini, I need Clem Cattini; who’s Clem Cattini?” he laughs. “I wasn’t a particularly proficient technical drummer. In fact, I’ve always considered myself a musical navvie.”

In reality, Cattini was the drummer of choice for artists like Billy Fury, Dusty Springfield, Lulu and countless producers. Aside from his number ones, Cattini was the sticksman on Cliff Richard’s Devil Woman, Lulu’s Shout, Gene Pitney’s Something’s Gotten Hold Of My Heart and Jeff Beck’s Hi Ho Silver Lining. Cattini was the drumming version of Jimmy Page – the guitarist is credited with playing on 60% of the British pop output in the 1960s before a certain group called Led Zeppelin came a calling. Which is no mere coincidence, because Cattini was considered for the drum stool in the supergroup before a guy from Redditch occupied it. He remembers: “I was very busy doing sessions. I had been on the road for nine years, and suddenly I was at home, getting into my own bed at night. Peter Grant (Led Zeppelin’s manager-in-waiting) saw me at a session, phoned me and asked me to go to lunch to him to talk about a project. We never had that lunch. Not for any reason. I was just too busy. He called again, but again we didn’t have that lunch.

“A year later, when Led Zeppelin’s first album was in the charts I saw Peter again and asked him if that was the project he wanted to talk about. It was, but there’s no point regretting anything. I can’t look back and change things. “It wasn’t a conscious decision, just circumstances. But there again, was I the sort of person that could go all around the world in that scene? I don’t know.”

Having played in Lulu’s backing band with future Led Zep bassist John Paul Jones, another busy 1960s session musician, and in many recording studios with guitarist extraordinaire Page, it is likely they recommended the Stoke Newington-born drummer to Grant. Legend has it that Cattini was again considered as a replacement for Bonham in 1975, but he has no knowledge of this and certainly says no approach was made to him.

I know it sounds preposterous, but this is true. I never set out to become a drummer. When I first started I didn’t know the difference between a crotchet and a hatchet.

It is clear that despite his good-humoured downplay of his talents, Cattini was concerned that his first number one would not be taken seriously by other, more classically-trained drummers. However, the emergence of rock ‘n’ roll was an advantage. “I know it sounds preposterous, but this is true. I never set out to become a drummer, but I went to see a guitarist mate of mine and he wanted to start a band. He told me I should be the drummer. I had no musical knowledge whatsoever. “When I first started I didn’t know the difference between a crotchet and a hatchet. But I could play rock ‘n’ roll and some of the ‘proper’ drummers just couldn’t. I came from a different background to most of my contemporaries, who came from the big bands. People wanted to hear rock ‘n’ roll and I was lucky. ”I think I got a bit embarrassed at first. When I did Shakin’ All Over I was into the big band music and Ronnie Stevenson, who played with Johnny Dankworth wanted to hear the single and I didn’t want to play it. But he liked it and I got a bit of confidence from that. “I don’t think I’m a technical drummer, but people tell me I’ve got good time and groove.”

In a setting where flashy playing was generally unnecessary, Cattini’s renown metronomic qualities and his ability to put heart and soul into a recording were his biggest pluses, but he could tear it up when he needed. And adopt a different feel at will. On one Top Of The Pops appearance, Cattini cropped up five times playing five different styles of music. Cattini has no regrets about playing on Renee And Renato’s chart-topper Save Your Love, Ernie (The Fastest Milkman In The West) a number one for Benny Hill, Clive Dunn’s Grandad or Windsor Davies and Don Estelle’s big hit Whispering Grass. “I was a session musician. That was my work. I got paid for it. I did it as well as I could. I’ve no regrets. I’m sure some of the music back then was as crap as it is today. It doesn’t bother me.” Famously one of The Wombles – “I loved The Wombles’ stuff, it was very musical” – Clem’s output in the 1960s and 1970s was prolific. “I suppose I got a reputation,” he says. “I was doing 21 sessions a week, sometimes more. Some songs were hits, others weren’t. Sometimes I knew who the track was for, sometimes I didn’t.”

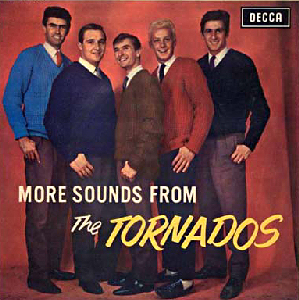

The Tornados

Cattini would also play on jingles as well as playing on the road. And playing on the road could be physically demanding in more ways than one. Drumming with Roy Orbison, Cattini was constantly asked to play louder by the “Big O”. “I was coming off with bleeding fingers I was hitting the drums so hard,” he recalls of dates at the Talk Of The Town. “He’d still want me to play louder. All of a sudden one night this guy appears before the drums and screams at me to “shut the F*** up”. Roy put him right and everything was fine, but my fingers were still bleeding.”

Union and BBC rules were among some of the frustrations in the early days. “We were playing live in the studio with the whole band in there. We were playing together, making music together. Then you were making a record. Now you are making a product. “When I started there was a union rule that stated you must have the singer in there with the band recording. It was stupid. I did something with Decca and it took 93 takes because the singers kept making mistakes. The band were doing their job right. And then sometimes, you’d get people substituting for the singer. It was a stupid rule and I was glad when it was scrapped.” The BBC’s ban on playing records with sessioneers was also a brief annoyance. “I played on an album called Rumpelstiltskin and we were session musicians and had to use pseudonyms,” he laughs. “I think I was down as Rupert Bear.”

But life was good for Cattini with a string of big hits under his belt, the 1970s saw him playing on T-Rex’s Telegram Sam, Get It On and Hot Love releases, Middle Of The Road’s Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep, The New Seekers’ I’d Like To Teach The World To Sing, Chicory Tip’s Son Of My Father, Welcome Home by Peters And Lee, Carl Douglas’ Kung Fu Fighting, Hot Chocolate’s So You Win Again. He also played on The Bay City Rollers’ studio recordings, notching up more number ones with Bye Bye Baby and Give A Little Love, while he was the drummer for The Brotherhood Of Man, which yielded another three chart-toppers – Save Your Kisses For Me, Angelo and Figaro. His last number one was Peter Kay’s Comic Relief re-release of Tony Christie’s Is This The Way To Amarillo in March 2005.

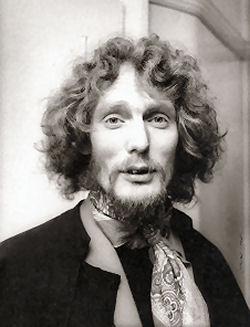

Clem Catini

But recently he has been reliving the glory of one of his most famous tracks, from his days as a member of The Tornados. Telstar was a huge hit in 1962 and became the first British single to top the American charts. It is now the subject of a film and Cattini got a cameo role in it. “Someone else is playing me,” he said. “I think my daughter was a bit more fazed by it than me. Apparently my character is quite aggressive in the film, which is mainly about Joe Meek (who wrote and produced the instrumental). “It was fun, though.” Telstar, named after a telecommunications satellite, boasted weird sound effects which, at the time, were believed to have been the actual signal from Telstar, but suggested to have been far more earthly. The ‘rocket lift-off’ is said by some to be Meek flushing a toilet.

Urban myths aside, it was recorded in double-quick time, with The Tornados, including rhythm guitarist George Bellamy, dad of Matt Bellamy, of Muse, breaking into a couple of dates at Great Yarmouth to return to London to record the track, before heading back to Norfolk the same night to play their live show. This year has seen Cattini still out on the road, the “boiler room” for Kenny Lynch. “I still keep busy.” Cattini has always been an innovator. “I think I was the first drummer to take the front of my bass drum head off and put a pillow inside. I also took the bottom heads of my toms. The sound guys loved it. “I started off with the classic four piece, a ride, crash and hats. Then I moved to four up, one down, trying to be flashy. Then I started getting older and went back to two up, one down.”

Cattini is a prince of pop, having played with everyone from The Kinks to The Bee Gees, Tom Jones, The Shadows in their Marvin, Welch and Farrar guise, and shared the drumming duties with Bonham on Page and Paul Jones’ Rock And Roll Highway album. And while he might not have got the Led Zep gig, he has finally been recognised for his drumming on Donovan’s Hurdy Gurdy Man. Until recently, it had been thought that Led Zeppelin as a whole were the backing band, but Paul-Jones, Cattini’s erstwhile session partner, was more than happy to put the record straight. It was Paul Jones and Cattini – that intriguing what if of British music, united time and time again but not in the ‘biggest band in the world’, and guitarist Alan Parker.

“It’s nice,” says Cattini. “I don’t see why they shouldn’t admit who played on what. But it doesn’t bother me. I’ve made a living out of it. I’ve enjoyed my life. My only regret is that seeing as those 1960s records have remained popular, I’d have probably played better on them if I’d have known.”

In the current fever surrounding Led Zeppelin’s reunion, it would be unfair to consider Cattini the nearly man. He wasn’t. He was the man who put the beat in dozens of classic records. His legacy remains.

Interview: Mark Forster