Clive Bunker

I met Clive at the services at South Mimms where the A1 and the M25 converge rather than going into London. The capital, having once been the place we couldn’t wait to get to at any time day or night, now doesn’t hold quite so many thrills for either of us. Unless of course we’re dropping into the drum shops in the West End to see what’s going on, or walking around Soho trying to recognise where things used to be.

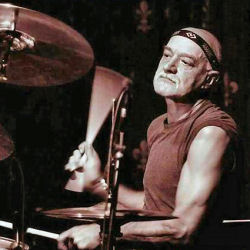

I heard you’re very busy and working really hard so I’m assuming you’re still having a great time playing drums? What’s keeping that spark going?

I think it’s the industry because you mix with young people, I know my exterior’s falling to pieces but inside I still feel, well… I don’t feel any different from 40 years ago.

No aches and pains?

No, it’s the gym isn’t it? I call my drum kit my gym now.

You’re absolutely right. So I’d like to talk about the days when we all got into bands when nobody knew how long it was going to last. What’s your take on that?

It was five years maximum for bands in those days. None of us thought it would last what with the nuclear threat going on. I remember in America you used to get it all the time, so that’s why I think most of those bands partied so much because they thought another few years we’re all going to be gone.

It’s weird though because nowadays it seems people get into the music business to make a few tunes, a lot of money and get the hell out.

I did get out. When I got married that was after five years [in the business] and I got out because I wanted to get married. We were just about to start our first world tour and then move to Switzerland for a year. So I’d been away for coming up 3 years, and I thought it’s not the best way to start a marriage. I never intended to be a drummer. When my school mates started to get guitars and suggested forming a band it was “right Clive you’re going to be the drummer” and it grew from there. I still class myself as a very lucky boy.

So they dragged you into drumming, was that rhythm and blues, what sort of band was it?

The first one was a covers band, just doing Cliff Richard and The Shadows. That was in Luton and then my parents moved to Dunstable, near the California Ballroom, that you’ll remember. I remember seeing you there. You were twiddling sticks and I thought how do people do this? It was great.

So you were dragged into Shadows music?

Yeah, that was still around, it was just a laugh really. When we played at the California Ballroom I never expected to play years later in California itself. To me that was the peak of my career. That was mid-sixties, 1963/4.

What was that band called?

Originally it was called The Warriors and then it turned into Yenson’s Trolls because a guy joined who was from Newcastle way and his middle name was Yenson, besides there was a band in America called The Warriors as well.

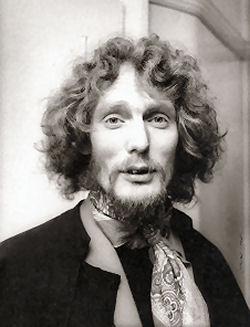

Clive (far left) with Jethro Tull

Now who was the real Jethro Tull?

He invented the seed drill. The actual bass pedals of an organ, that’s where he got the idea because when the things sticking out he thought if you had them hollow and drop seeds through them and stuck it in the ground, you could make a seed drill, which he did. So there was a musical connection there.

What drum set did you have with the Trolls?

My mum and dad bought it for me out of a club, a blue sparkle Broadway, which was fantastic at the time. I always saw people like yourself with these amazing kits and I thought “one day” and then I might sound good. Wrong!

I don’t know if you know his name, but there was a session drummer, a Scottish guy, who used to play with Dusty Springfield, and we were on the little stage and they were on the big stage. I had a chat with him in one of the breaks and I said “I wish I had an amazing drum kit like yours and then maybe I could make it sound pretty good” and he said “Don’t pack your kit away” and when people were going, we had a chat and he sat on my kit, played it and he said “There you go, when you learn to play, you can make anything sound good”.

It takes 50 years in my opinion to learn what to leave out. Of course there was a time especially during your Jethro time when more was what was required, not less.

It was the time then when most of the audience were stoned out of their mind on something, so yeah, drum solos, guitar solos, they were all about 20 minutes long.

When we brought the Isle of Wight Festival DVD out, I just couldn’t believe how long the drum solo was. Then I saw Zepplin’s DVD and Bonzo solo’d for something like 30 minutes so I thought “Ah, it wasn’t that bad”.

My first really long drum solo came about by accident. When Tull started to get a bit more popular we played this little club and the band went off in the drum solo and I did my little riff to finish and they weren’t there. So I carried on a bit more, did my little riff again and they still weren’t there. They couldn’t get through the crowd! That was my very first long drum solo.

There was always a shape to it, there had to be a shape to it otherwise no-one in the band would know where they were.

Yeah the way we worked with Tull which was the same with some of the guitar or flute solos, there would always be a the little riff at the end of it. If someone thought of something different to do they had the freedom to do it.

So after your blue Broadway kit what did you get then?

This manager had a Ludwig drum kit which was heaven on earth, but it was his drum kit, so I used it until that fell to pieces! It was the same as Ringo’s – Oyster. After that Mick Abrahams had joined the band for the last bit so he said let’s form another little band which we called McGregor’s Engine. I was back to having to get a drum kit so I had an Ajax bass drum, Carlton tom-toms and Premier snare. It was white with a 20″ bass drum, then I bought an 18″ bass drum and bolted the two together so I had this huge long bass drum which to me sounded wonderful. It was all white so they sprayed it in squares, it was a weird looking kit, but it worked, it was great.

Early Tull

So this 18 and 20 together looked like a telescopic drum even though it was bolted.

Yeah right, it was 20 at the back and 18 at the front

You didn’t use that with Jethro though did you?

No, I don’t know what I had up to that. After that I ended up with the same toms and snare drum but I took all the squares out of it. I think I still have the bass drum but I took the 18″ off it.

So this was after the Ludwig kit? So the Ludwig kit belonged to the manager so you left, so we’re still not up with Charlie yet but you’re playing with Mick.

Me and Mick are playing together, then that band finished and that was me out of music, we were still semi-pro anyway then. He moved to Manchester in a band called The Toggery Five, and he phoned me up a few months later and said do you fancy joining the band and going professional. So I thought about it for 20 seconds and up to Manchester I went.

It was a clothes shop wasn’t it the Toggery?

It was, they sponsored the band and then we did the German clubs and the band fell to bits in Germany basically.

What year are we in?

1966 in Germany, a great time to be in Germany. I had a girlfriend, she used to work in a beer club and we used to finish about 4 in the morning and she would finish about 6. So after the gig I would go down and see her and there were a bunch of German blokes in there and when they heard me speak English to her, it was ‘Oh English, good team, good team, we buy you a beer’ and I thought here we go, 6 of them 1 of me, they’re going to buy me a beer and I knew what was going to happen. So they brought me a beer and then it came and they were like ‘Right now you buy us a beer’ ands they thought they were really clever buying me one and I had to buy 6 but what they forgot was the barmaid got concessions on the drinks, so it didn’t cost me a penny. This was just after we’d won the World Cup. Then the band broke up in Germany and I ended up in Dover or somewhere at the train station with a drum kit. I had to get my drum kit about on the train. Try doing that nowadays.

You can do it with some kits but you certainly couldn’t do it with the sort of kit you had in those days that’s for sure

And that was it, finito. Mick phoned me one day and said he’d seen a great band, at a club that our manager at the time ran in Dunstable and he said next time the band are down you’ll have to come and see them, which we did. They were called the John Evan Smash: John Evan, Ian (Anderson), Glenn, and all the band. Then that band split up and we all started moving back to Blackpool but it was like an 8 piece soul band. Then I think Barry was the last one to leave which I think would have been the end of that. Mick suggested to Ian, Glenn and me that we form another blues band because they still had some gigs to do. So we turned up as a little old 4 piece. I think the management, Terry Ellis, was talking to these club owners and apparently they were saying they thought it was an 8 piece band and there were only 4 of us but we were really good. So he got in touch and said he would come and see the band and he liked it and said all you need is to be in the right gigs. So he booked us into blues clubs.

…the truck had reversed over the kit and all that was left was the bass drum and snare drum.

Did Ian play Sax then?

No it was just guitar and harmonica. Over the course of it he would bring the flute out and I thought ‘Yeah, right, a blues band with a flute’! But it worked and the image of Ian came about because we were doing some really ropey little places and there were a couple that were really freezing and Ian had gone into a charity shop and brought a big coat and he wore it on stage and Terry said he thought it was a great image. Then away it went.

What drum kit did you have then?

Still the same kit, the hybrid. It was only when we did the first American tour that Terry said “Right you’re doing OK, go and get yourself a drum kit”. So I went into Manny’s and brought a double Ludwig and I couldn’t even play hi-hat but he said “Right you’ve got it, you’re going to use it”, so it was set up every night and I learned how to play it.

What colour was that one?

The same, Black Oyster. I turned up at a sound check and walked on and there were the lovely bass drums and snare drum but the tom-toms were missing and I asked Roy, the drum tech, what had happened, and he said the truck had reversed over the kit and all that was left was the bass drum and snare drum. The next morning we went and brought the rest of it.

So now we’re up to you’re doing well with Jethro Tull and you’ve gone to America.

Yeah, it was 1968/9 and it was just endless touring with the band really until the tour before the last one. In the break [before the tour] I’d met this girl and it was during the next tour I was speaking to Eric Brookes our tour manager [about leaving] and he was saying I was mad and everyone was saying I was mad and then I had a chat with Ian and Martin and we left it at that because it was a long tour and I don’t think Barrymore Barlowe knew what was going to hit him when he went to America, the huge stadiums. So we left it that if he had a bit of a problem with it I wouldn’t mind going and doing the odd gig until he got himself together, but he did.

So what had Barry been playing up until then, had he been playing jazz?

Just in a pally band. After the John Evan Smash, he played in a local pally band and that was one of the problems I thought he might have because he was a fairly light player. We had got in the habit by then of smashing the hell out of it.

Because of the PA’s and because of the size of the places if you played too technical it would just end up rubbish. The only good places where you could get away with it were the Filmores [Bill Graham’s gigs in New York and San Francisco]. The first gig we ever did was supporting Blood, Sweat and Tears there. But they couldn’t understand us. They’d all gone to college those guys and they were too good if you know what I mean.

So you’d officially left Jethro Tull, so what were you up to?

So you’d officially left Jethro Tull, so what were you up to?

I took a year off to think about what I was going to do and I ended up starting a coach company, a little studio in Luton and an engineering company with multi-spindle lathes. Then I brought a farm and started a dog boarding kennels. I had the local paper come round to do a little interview, something like ‘Rock Star Goes To The Dogs’, brilliant.

Was it an alternative career, was it lucrative, do you make money from that?

Yeah, but that wasn’t the main money spinner, the factory was. That was huge, and it didn’t take much of my time.

What sort of stuff were you making there?

Everything for the aircraft industry, Black and Decker we did loads of bits for their drills, all the motor companies, international harvester for tractors. It was great.

How long did that last?

I left it when the marriage split up which was 15 years ago now and that was obviously because the business went in the settlement. Then I just spent a few years thinking ‘What am I going to do now’. I went backpacking: Central America, New Zealand, all over the place, Asia. I thought I’m in trouble. I got the odd gig, did the odd tour, then a rest period. Then about 5 years ago it got more and more busy and I started playing all over the place.

I know this should be a bit later on, but you’ve been going to Italy a lot, is that with Gathering?

I don’t know if you remember PFM?, I did an album for Bernardo Lanzetti the singer after he left them and so there’s a Tull Tribute Band that I go and do some stuff with and Bernardo comes with them. So we do some of the old PFM stuff and some Tull stuff.

And all this is in Italy?

Yeah. I was out there last week with a little blues band. It’s all over the place, not just Italy but all over the places where you didn’t used to go, like Prague. Brilliant. I did that with a band called The Twin Dragons. I think they’re still playing, I see posters up at clubs I do now. It was an Italian guitar player, American bass player (huge black guy with tattoos) but they were really good and I enjoyed playing with them but I didn’t get on with the management at all.

Tell me about Jude?

That was just after I got married. Chris Wright from Chrysalis phoned me up and said Robin Trower and Jim Dewar and Frankie Miller were getting together. Did I fancy playing drums with them? It was a vocal band and the two Glaswegian voices together was just heaven but I think Chris Wright wanted another ‘Ten Years After’ really, with Robin as a guitar hero. So he wouldn’t let us record, wouldn’t let us go to America, so we all went into the office one day and said ‘What’s the crack here?’ and we said if you want the guitar hero thing, start one, we’re off. So that all finished then.

So Gathering, how did that begin?

So Gathering, how did that begin?

I’d been doing bits with Jerry Donahue, one band that we had together with Leanne Carroll was heaven. I said to Jerry “Let’s keep this together because it’s marvellous” but it fell to pieces. We should have gone to Denmark or Norway to do an album and Jerry, everybody thought, was going to sort the business out, but it all fell through. Then this agent put another band together with Jerry, he phoned me and asked if I wanted to do it. I’d never met Doug and I’d never met Ray but I knew what they were about. We went for a couple of days rehearsal and within five minutes we all knew it was going to work.

How long has that album been out?

I don’t know, not that long. Jerry phoned me up and sent one last week and he didn’t say whether it was out then or not, whether it’s available now, that’s the point of it all. We went to do it in Germany and some of it was on one digital format and when they moved it to another digital format and it came to mixing, for some reason a lot was lost and they couldn’t get it up. There’s loads of percussion that’s not on it.

So that’s out and that’s what you’re plugging, are you going on tour with that?

Yes. Unfortunately the tour dates I was given started on whatever date it was, but then the agent put a couple of festivals in a few days before. I’ve got these gigs that I can’t get out of so Paul Burgess is doing the first three gigs, then I’m flying to Italy in April.

That’s quite a career isn’t it. So what sort of drum kit are you using for Gathering?

For that it’s a little Yamaha 20″, 8, 10, 12, 14 concert toms; and bongos. It’s almost like back to Tull, that’s how we started with Tull, I’d only play drum kit for just over half the set, the rest was percussion.

Do you collect drums?

No. Sometimes I think back and think ‘If I had kept that’ but no. I don’t class myself as a drummer. I remember Dave Mattacks, he was in the row behind me on a plane once and he tapped me on the shoulder and he was pulling these photos out of his wallet and I thought oh it’s the family, and it was photos of his antique snare drums, I said ‘You are very sad’.

The problem there is especially with the Gathering, is all the percussion I need.

I don’t know about you, but like last week when I was doing this little blues thing, I still had to have my double bass drum pedal because it determines where the hi-hat goes. I didn’t use it, it was there, but I didn’t play it.

I did a gig which Jerry Conway couldn’t make with Pentangle. Jackie phoned me up and said can you do a few gigs with them, at the end of the set last number there’s a drum solo that Jerry used to do and so Jackie said do a little bit of a solo. I started this solo and I thought “Hang on this is Pentangle. Shall I shove in a double bass drum pedal?” and I went for it. They loved it.

Do you ever play with Mick Abrahams these days?

Do you ever play with Mick Abrahams these days?

Yeah, every now and again, a little blues band or something. I just finished a tour with Don Henley, that was amazing. He’s just brought out a CD and he’s got Rob from Jamiroqui on guitar, Lawrence Cottle on bass and Steve on vocals, it was just heaven, but difficult and heavy, it was in 7s and 5s, but it was amazing.

It’s the ying and yang. I suppose it was with Tull as well, when you’re playing really softly and then next thing is launching into something that’s heavy rock really, or stadium rock even.

Again that was the joy of Tull, doing little bits of percussion, gentle stuff and after you’re going for it. All of what I enjoyed playing was in one package. Now with something like the Gathering, they call is folk rock. Christina, in her band in LA they play a lot heavier and so when Christina sings stuff live with the band it’s the heavier stuff.

You played with Manfred [Mann] as well didn’t you?

Yeah, I was sitting down having a chat with Manfred one day and he was asking about being in the music business and I said to him, no I’m just a lucky boy. That’s his whole thing about music, he says everyone that’s made it has had luck, but once you get the luck you’ve got to be able to back it up. That says it all.

I like him, he used to produce us, very interesting times.

I think when I did that album I was in there for a couple of days, I did most of the backing tracks and it was going on and on and on and then I went in one day and said what’s happening, he said ‘I’m just going through a few things’ and there was a new toy that had come out and he had moved the bass drum every which beat you could through the song to see what sounded right and I said ‘I’ll leave you to it’. He phoned me up one day and said we’ve finished and you’ll be pleased to know everything is exactly how you played it. He had spent two years doing all this stuff. I think its technology, when technology comes out people think they’ve got to do it.

But if you don’t try it just like everything else in music you don’t know if it’s any good. That’s the other side of the coin.

Exactly!

Check out Clive’s solo on with Jethro Tull on Youtube. It’s introduced by Carmine Appice and titled Classic Rock Drum Solos – Clive Bunker.