Henry Spinetti

Henry Spinetti has had a glittering career which shows no sign of slowing down. So far he’s played among others with Joan Armatrading, Eric Clapton, Roger Daltrey, Leo Sayer, Bob Dylan, Joe Egan, Paul McCartney, Procol Harum, Pete Townshend, Cliff Richard and Katie Melua.

I happily spoke to Henry (with a little help from Mike Dolbear) at London’s Hard Rock Café on Zildjian’s artists’ day in March 2010. However, my recorder ran out of batteries so I didn’t get round to asking what he’s up to now.

So you grew up in Cwm near Abervale, what was the music scene like in Abervale other than male voice choirs?

Well, I started off in a band and played a couple of Shadows things, then I went to another band and they were playing things like ‘Boney Maroney’. Then it was things like ‘Pretty Woman’ and ‘Route 66’.

So what was your first drum kit Henry?

It was a Cream Gigster bass drum, with a drum stick pushed in the hole with a little cymbal on it and an Ajax Piccolo snare – I wish I still had it – and a hi-hat; that was it. The bass drum I bought off a cousin of mine and I hounded my father to buy me a kit. My cousin managed a band and when we used to go down and visit he sold it to me for £18.

What year was this?

I don’t know, I must have been 12, so 1963.

I know that but there are certain things I think I should learn, like reading for a start

And did you take lessons?

No, I sometimes wish I could start now.

MD – If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it

I know that but there are certain things I think I should learn, like reading for a start.

MD – Gilson Lavis asked me this, and he said ‘I’m going to come to you and get some reading lessons’ and I said ‘Who have you played with?’ and he reeled off some names, and I said ‘So why bother?’ I think if you have only one sense, you’re using your best sense.

I hear what you’re saying and I think that’s true.

The problem comes when someone gives you that part and you panic

It’s not just the part, there are certain places where the phrases have to be and you’re in there with a bunch of people who go ‘Oh yeah’ and they just write down this phrase and they’re using their feel in their way until they get to this phrase and sometimes there’s me going ‘Oh, I don’t quite get that’.

Henry with Yard

But it’s never that difficult to play is it?

No, and we’ll go over it and then you get it in the end.

So that’s something you’d like to do Henry but like most guys I assume you have your own way of doing it?

I can make my own way of doing it if someone sends me something [to listen to] – I just count bars. There’s always something that catches me out and that’s when I think ‘Hmm…’ but it’s not done me any harm I don’t think.

Your brother is an actor who amongst many other things was in three Beatles’ films and ‘Oh, What A Lovely War’. How much older than you is Victor?

He’s old enough to be my dad, but he’d kill me if I told you.

I was into horse riding; I wanted to be a jockey before I saw the Beatles on ‘Thank Your Lucky Stars’. It was kids in school who said ‘Have you seen that group, The Beatles?’ I didn’t even know what they were talking about.

So there’s no chance you might become an actor?

No, Victor was the actor and he was always the ‘big bruv’. Of course the funny thing was that he was definitely a big influence but I didn’t want to be the same as him. I was into horse riding; I wanted to be a jockey before I saw the Beatles on ‘Thank Your Lucky Stars’. It was kids in school who said ‘Have you seen that group, The Beatles?’ I didn’t even know what they were talking about.

I was riding in gymkhanas, I was only about 11½, I loved it, used to brush it down, I was going to be a jockey because I was little, and my sister-in-law said to me when we sat down at the dinner table ‘Henry, I think you should go to the doctors’, I said “What? Why?’, ‘Well, he might give you a certificate to shit in the street’, because I stank like a horse. I didn’t realise.

Then of course, eventually I did see The Beatles and it turned me and I just thought ‘I’ll have some of that’, I thought ‘I don’t want anything with notes, I’ll be Ringo, because that must be easier’ – little did I know.

So what got you from watching ‘Thank Your Lucky Stars’ and not wanting to be a jockey anymore, to ‘The Herd’ and what was that the first thing you did?

Well, I hounded my dad for this kit. I started to refuse to go to school, it was terrible, the thing was my dad had a fish and chip shop (he’s Italian) and a café next door that sold ice cream. I went to a Secondary Modern and they taught you pass your 11+ (because I wasn’t brainy enough to go to the local Grammar school) and you became an apprentice in the steel works and if you fail that you go down the pit. So I thought ‘Not me, I want to be a drummer’. They all thought I was bonkers. My parents, especially my mother, thought ‘OK’. So I just wouldn’t go to school and I would be at home playing to The Beatles. My brother Victor bought us this stereo, the speakers would clip on top and bottom and you would play the vinyl in the middle, so I got a tape recorder and got a balance so The Beatles were fairly loud so I could hear them and me on the drum kit, so I could tell when I was going off. It actually taught me quite a bit about timing quite early on. I always thought they were great, I loved them.

You eventually played with two of the Beatles didn’t you?

Yeah, amazing.

I went around Wales. I went from this band ‘The Toby Four’ (there was a beer called Toby in Wales) we used to rehearse in the Ambray Hotel and so they said they’d let us rehearse in there for nothing if we advertised the Toby beer, we played a couple of Shadows numbers and things. Then it wasn’t too long before these chaps came in from a band called the ‘Hot Rods’ and they came in for the beer. I was only about 12½ or 13 and they were about 21 and I’d been for an audition for them but I’d failed. Anyway they happened to call in for a beer and they heard this playing going on and they said ‘Is that you, Henry? How come you didn’t play like that when you came to the audition?’ I said I didn’t know, you know, young boy, so I joined them.

I went around Wales. I went from this band ‘The Toby Four’ (there was a beer called Toby in Wales) we used to rehearse in the Ambray Hotel and so they said they’d let us rehearse in there for nothing if we advertised the Toby beer, we played a couple of Shadows numbers and things. Then it wasn’t too long before these chaps came in from a band called the ‘Hot Rods’ and they came in for the beer. I was only about 12½ or 13 and they were about 21 and I’d been for an audition for them but I’d failed. Anyway they happened to call in for a beer and they heard this playing going on and they said ‘Is that you, Henry? How come you didn’t play like that when you came to the audition?’ I said I didn’t know, you know, young boy, so I joined them.

Then I joined another group called ‘The Choice’ from Tredegar, and then Hendrix started to come into it and the guy Tom Prosser used to play behind his back. It was a 3 piece so it was looser, and then I got into a group in Cardiff called ‘The Clockwork Motion’ which started to break out, do Newcastle, Birmingham. Of course they broke up as bands always do so I went back home and I was sat at home thinking ‘What am I going to do now?’ So I forced my brother Adrian, who owned another fish and chip shop in the family, to help me. I used to get chips out for him, I knew he’d give me a fiver or a tenner and my mum used to say ‘Go and see Adrian, he’ll give you some money”. I was about 16.

I’m assuming by this time you definitely haven’t got the Gigster drum kit have you?

No, Premier now, Black Pearl.

So, I’m sat at home wondering what to do and there’s this guy who was in a London band called ‘Floribunda Rose’, his name was Jack Russell and he was Welsh and he ran Maurice White’s Music Shop in Newport. He said to Maurice ‘Do you know any drummers? I fancy somebody Welsh’, he says ‘No, I don’t Jack, hang on a minute, I’ll ask around…’

Well, there was a bloke who used to come into the fish shop and he’d heard me play in this group called ‘The Choices’, he said ‘Yeah I know a drummer, a young guy, he’s really good … you can get hold of him through the Cross Keys Fish Shop’. So Maurice White then says ‘Jack, there’s a guy called Henry Spinetti, you can get hold of him via the Cross Keys Fish Shop’, so he gave him my number. He rang the house and asked to speak to me. ‘Do you fancy coming to London for an audition?’ and he asked what I looked like. My mum shouted ‘Tell him you look like Tom Jones, love’; I told Tom that as well! So I went to London, drums on the train, my dad took me down, I was sat next to the carriage with my drums, kept checking them, got off at Paddington and I had a six wheeler transit. So they had a flat in Earls Court, we did four or five numbers and I got the job, this became ‘Scragg’ and we went to Hamburg, the Top 10 Club.

How old were you then?

I was only 16. I should have been off the street at 10 o’clock

So we went there [Hamburg] knowing one number and came back knowing about 200

You were probably only just getting into it by 10 at night

Yeah that’s right, playing from about 8 or 9, you know that scene, an hour on, an hour off until sometimes 5 in the morning. So we went there knowing one number and came back knowing about 200.

How long were you there for?

Only 2 weeks.

Did you enjoy it?

I loved it. It gave me a chance, there were only certain numbers I knew, the amount of numbers grew because if you only knew 5 or 10 you had to keep repeating them so it gave you the chance to try this fill or that fill and then we were really good when we came back.

So you went to Hamburg with Scragg. John Kongos (of Tokoloshe Man) was in that band too, what was he playing?

Guitar, Jack Russell was the bass player and then there was a guy called Chris Demetrio on organ. Jack Russell had been to South Africa and had met John there and then came over. I didn’t play on Tokoloshe Man.

the audition was so long and of course by the time it came to mine I was glad to do something, so the nerves had gone, I just bashed it out really, as long as it was loud and solid that’s what they were looking for.

So you came back from Hamburg and then you did The Herd?

Yeah, as bands do, somebody squabbled, somebody wanted to get married, and somebody wasn’t earning enough money so they had to get a job, blah, blah, blah, so that disbanded. So there I was in Earls Court in London, so I rang home and was told they couldn’t send any more money, you’ve got to get on with it. So I lived on porridge basically.

I had another brother who was trying to be an actor, his name’s Paul, and he had a job in Selfridges in London in a warehouse on the floor that sold beds, blankets, cushions, pillows, and he got on well with a bloke there and they took me on. I lasted two weeks! While I was there I was hunting the Melody Maker for gigs. This old boy said ‘Don’t worry about it, you just keep looking at your magazine’. I was hopeless, that’s all I could think about. It was always the ones with a big square ad “drummer wanted”.

So I got an audition for The Herd and it was in a club in Swallow Street and I went along for that gig and got it. I don’t know why, I saw drummers there, I thought ‘He’s good, oh well’, and the audition was so long and of course by the time it came to mine I was glad to do something, so the nerves had gone, I just bashed it out really, as long as it was loud and solid that’s what they were looking for.

Did Judas Jump come next?

Yes, but having played with The Herd with Andy and Gary they knew a few producers and sometimes there would be a session, and there was a producer guy called Steve Rowlands, I was dumbfounded that anybody would want me to play on their recording. You know what it’s like; you would do it for nothing wouldn’t you? I started to dribble into sessions as well, so in between The Herd and Judas Jump the odd session started to creep in.

And did Judas Jump come along because Amen Corner had split up?

Yeah, Amen Corner had split up, Andy (Fairweather-Low) had gone out as ‘Fairweather’ and he had a hit ‘A Natural Sinner’. Alan Jones from Amen Corner was still involved with Don Arden, he was the manager, he suggested to Don about getting the singer called Adrian Williams, and he knew me from The Head, then Andy Brown was approached, that’s how Judas Jump started. We got some money as well, believe it or not. Everybody called Don Arden all sorts of names, but we got an advance. We didn’t have to pay it back.

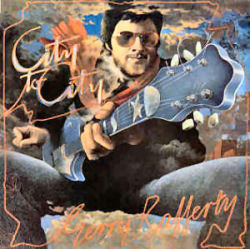

City To City – Jerry Rafferty

Was Hustler the next band you joined?

No, I think sessions started to kick in but it could have been. You might be right.

I know Tony Beard left Hustler

The Hustler boys told me he decided to do it properly so he went off and got taught how to read and everything, he was a great drummer.

The thing about any particular gig is all you can do is be you

That’s the fantastic thing about Eric Clapton you know, he never tells people what to do because he’s got a really good idea of what they can do and then let them get on with it.

I understand it’s the same with Van Morrison but if you don’t do what he’s got in his head you’re finished. He’s not going to tell you what he’s got in his head, but if you don’t figure it out, that’s it.

What was the first hit you played on, was Baker Street around this time or was that a bit later?

Baker Street was just after Judas Jump split.

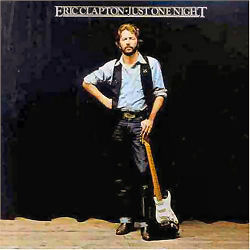

Eric Clapton – Just One Night

So then there’d have been Daltrey before that. Did you do Daltrey and Leo Sayer at Roger’s farm?

No, it was in The Who’s studio. Adam [Faith] formed a band for us to audition down in Brighton in some club. I can’t remember the studios because I didn’t do a lot with Leo, I did the odd thing, it was some studios in London, I can’t remember, I was young. There was another band called ‘Denick and Armstrong’, they came in after Judas Jump because the keyboard player of Scragg now wanted to be a producer and he was doing something with Active Management which was Cat Stevens, so he found ‘Denick and Armstrong’ and called me up to play on their album.

Was that a band as well?

Yeah, it was a band. It was now I started to realise that maybe I should be back in a band because as great as sessions are, how many times do you want to be called ‘Drummer’? ‘Denick and Armstrong’ had an album out, lasted a while but we broke up. I think I’d already done Jerry Raferty because when we were speaking about ‘The Herd’ Gary Taylor was the bass player and he was very friendly with Hugh Murphy and after ‘Denick and Armstrong’ split up I was absolutely penniless again, I didn’t know what to do. I rang up Gary Taylor because I knew he had a flat in Streatham and he put me up in his junk room, where he used to throw all his stuff. Of course as a result Andrew Steel did some stuff with Jerry Raferty that was ‘Stuck in the Middle with You’. Then I don’t know what happened to him, but again Gary suggested Hugh Murphy so we did an album with Jerry called ‘Can I Have My Money Back’ and that was an album that came before ‘City to City’ which Baker Street was on and there I was in Streatham in Gary Taylor’s house, got some money, then I could afford a flat again, I lived in Fulham then, sessioning then was my living.

Did you ever get any royalties, did anybody every say to you do you want session money or royalties?

There was only one person that ever offered us royalties and I still get it, Eric. He and his manager, Roger Forrester, gave us a point each.

What was that on?

‘Just One Night’, a double album. Then there was another album he did called ‘Another Ticket’, and we only got ¾ of a point then because Gary Brooker had joined the band, but they were the only people that ever offered that.

all of a sudden Bob [Dylan] arrived, he had real dark glasses on, he couldn’t see through them. I went up and said: ‘Hi Bob, my names Henry, I’m playing drums’, he just looked at my hand, he didn’t appear to be that friendly

So we’ve touched on Clapton but what about, Dylan? How did you come to play with “the greatest poet of our time”?

Dylan came over, he was doing a film, I forget the name, he came over to England and he rang Eric. I was now not in Eric’s band but I can’t remember the date, he rang Eric, I was living just outside Guildford, not far from Eric, he said ‘I’m in town I need a drummer, can you suggest anybody?’ Eric said ‘Oh yeah I know just the guy’ so Eric suggested me for this session. On this session was Ron Wood on bass, Eric on guitar, me on drums, Bob Dylan on whatever. Ron was still a guitar player with The Stones, I can’t remember when this was, it could have been the ‘90’s.

So how did you get on?

I went in, set up the drums, all of a sudden Bob arrived, he had real dark glasses on, he couldn’t see through them. I went up and said: ‘Hi Bob, my names Henry, I’m playing drums’, he just looked at my hand, he didn’t appear to be that friendly. I just thought ‘Okay’. Eric came in, then Ron, the next amazing thing was Bob picked up a Telecaster and near this amp was a bass amp, he plugged into it he put a microphone right in front of him and started to play. Of course, I’m behind Bob in a booth with glass doors, so I thought ‘I suppose I’d better join in then’. I join in, everybody joins in, and that’s one tune. He starts again, that sounds ok, and he starts again.

No count in?

Nothing, he didn’t even say what key it’s in, no clue whatsoever. He just started to play, this went on for a couple of days. It was film music for this film, ‘Hearts of Fire’, one track from that recording which was the one that was most together, because there was a bit of form to it. I don’t know, Bob Dylan is obviously really clever, maybe he was making it all up on the spot. There were a couple of tunes that did have a bit of form and we followed as best we could and it came on to one of his albums. I didn’t know I had anything to do with that until years later when I got off a bus with Katie Mellua in Germany and there’s these anoraks, lovely people, with the album. Well they gave me this Bob Dylan one and I said ‘What’s that? I’m not on this’ and they said ‘You are’ and there it was. So I’m on a Bob Dylan album so then I got a friend of mine to buy a copy off the internet, because I didn’t know, just as a keepsake.

…and Katy Melua too

You played for an awfully long time with Joan Armatrading, didn’t you?

I was in her very first band, we started to do tours. We did Ronnie Scott’s and then went out touring with Jose Feliciano, I think she branched out with various people, I only did one track on her first album. Then I started to do sessions with Glyn Johns but they weren’t like sessions, they were like playing in a band, and I was very happy about that because it got me away from 10-1, 2-5 and ‘Hey, drummer!’.

How I met Glyn Johns was because I played for a long time with Andy Fairweather-Low. Just after ‘Wide Eyed and Legless’, he did an album ‘La Booga Rooga’, which Dave Mattacks did and then Dave Mattacks ended up with Joan and I ended up with Andy. Andy suggested me to play on his album called ‘Bebop and Holler’, Glyn wanted Kenney Jones, because he did some stuff with Joan as well. So there was a big gap between Joan’s first band and then working again in a studio but it was because of Glyn Johns.

He [Glyn Johns] told me a great story about Charlie Watts once who I think was grossly underrated. He used to arrive minding his own business and he was always dapper, he would take off his overcoat, and he would just hang it over the front of the bass drum. Glynn said that was the bass drum sound and it stayed like that. I heard a track by The Stones the other day, I can’t remember the name, and the drumming on it was unbelievable. There was lots of early stuff.

Lots of drummers used to take the Mickey out of Charlie, because they would struggle to make the off beat and the third and seventh beats on the hi hat coincide but Charlie didn’t bother to play beats 3 and 7. This meant there was a nice big gap for the off beat to fit in. The off beat could come almost wherever you wanted it; you weren’t bound by the eighth notes you were playing on the hi-hat. Interestingly enough, if you play with that gap on your hi-hat where the snare drums comes, it actually sounds like Charlie and it makes the track sound like the Stones. If you don’t do that it’s too rigid for them, it’s very weird.

I’ve got Tina Turner written down here tell me about her.

That was after Eric Clapton. We got, well I call it, fired, although he says he never fires anybody.

We were in the Bahamas, Compass Point Studios and it wasn’t working out and he [Clapton] said ‘Sorry, I’m going to get some other people in’ and I thought fair enough.

He just didn’t call you?

We were in the Bahamas, Compass Point Studios and it wasn’t working out and he said ‘Sorry, I’m going to get some other people in’ and I thought fair enough. It was quite upsetting actually. What I mean by upsetting, it’s because you always want to please.

Yeah, because it’s bad for your ego isn’t it?

Yeah. But I think he did the right thing for himself because the thing is we did get points but there wasn’t a lot of live work. I didn’t realise how far gone he was, but physically he could only do so much, so there wasn’t a lot of live work, so it was a good idea for the management to give us points because they didn’t have to pay us wages, it was a clever way round. Talking about that when you sat down in front of his manager Roger Forrester he said ‘How much do you want?’ You could have said anything, all I said was ‘A fair deal and to get it’.

And you did. I once heard that Roger came from a road crew situation? If that’s right then he knew all about musicians

Whereas a lot of others didn’t. But whatever we agree on is one thing, to actually get it is another!

I got a call, ‘Would you like to come and do an audition for Tina Turner?’

I’ve got lots of other names in my notes can we get into them?

Let me tell you about Tina first. I was sat at home; I was very disheartened, after Eric. I was reading the Bible a lot, I had money in the bank, I was married, I had my first child, a boy, so I was at home thinking just chill out, the miracle of a baby and all that. So I sat at home and didn’t play for 14 months. I didn’t want to play, I just don’t know, whatever’s next I’ve got some money in the bank, here’s my son, it’s up to you. It was like that. After 14 months I started thinking that the money’s running out and somebody put me on to selling vacuum cleaners. It was a friend of mine whose mate did it and he said why don’t you have a go? And I thought alright – it made enough money to buy a new lawnmower and that was it.

I got a call, ‘Would you like to come and do an audition for Tina Turner?’ I thought it was all over and didn’t know what to do. She came over; she was over-dubbing and singing the song ‘What’s Love Got To Do With It’. Terry Brittan had done all that, she said she needed a drummer; her drummer had left, because at this particular point in America they thought she was finished, she was an old cabaret act. Terry said I know two guys, one’s Henry Spinetti and the other’s Terry Williams, so I went and did the audition. I had to set up in a vocal booth and she came in and said ‘Hi’.

To us she was no has been, to the English she was like ‘Wow, Tina, blimey!’ She said ‘What do you want me to do? Do you want me to hear you play or do you want me to come in and dance?’ She said ‘Play a groove’. When she hasn’t got her mic she uses a pretend one. She says ‘When I go like that [with my arm] – stop, when I go like that – push it a bit; when I go like that – pull it back a bit. Okay, you’ve got the job’. This was after 5 or 10 minutes, but I found out later, I had a good back beat for her to dance. But, six months in America, my kid was now one – I had to go.

I had to go too and hadn’t got around to talking about Georgie Fame or Sir Cliff but we’ll get back to them in the fullness of time…

Bob Henrit