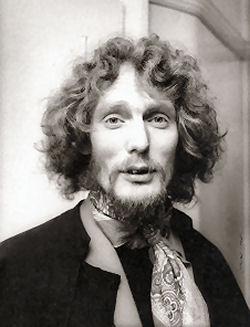

Kenney Jones

Kenney Jones – 40 years of Rock’n’Roll

Ringo, Charlie, Keith, Mitch, Ginger… and Kenney. When the Small Faces charted in March 1965 with ‘What ‘cha Gonna Do About It’, little did we know the little giant soulsters from East London would deliver some of the most exciting hits and inspired performances in rock history. Or that the drum intro to that hit was our intro to Kenney Jones, a wide-eyed youngster whose rock-steady grooves and big sound would serve as a template for Humble Pie’s Jerry Shirley, the Black Crowes, Paul Weller, Oasis and so many other major-name players (and their producers).

With Dansette turntables and radio stations around the nation spinning their hits ‘All Or Nothing’, ‘Here Come the Nice’, Itchycoo Park’, ‘Tin Soldier’, and #1 album Ogden’s Nutgone Flake, the Small Faces were stars. Beatles and Stones fans now wailed for these young Mods in Carnaby Street clobber, while musos like Hendrix dug their sound and soul. When the Small Faces dropped the ‘Small’ and added Ronnie Wood and Rod Stewart, they got big. Globally big! The Faces, boozy and loose, epitomized good time rock ‘n’ roll, with Kenney’s thundering drums on ‘(I Know) I’m Losing You’ a real showstopper. The Who would later choose him, a mate from early days, to be the final quarter of their reformed foursome and first farewell tour. There were other sessions and bands including Joan Armatrading, Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, David Essex, John Lodge (Moody Blues), Wings and the Law with Paul Rodgers… But whom he’s played with isn’t as important as what he’s played. The fact is that Kenney Jones is Kenney Jones in the same way Ringo is Ringo: he’s the One! And when that casually stumbling fill at the end of ‘Tin Soldier’ thunders out of the speakers, one is reminded that Kenney Jones epitomizes the creativity of the Sixties, the power of the Seventies, and the spectacle of the Eighties that made rock music so exciting and drumming so great.

It’s always great to see Kenney so I caught up with him at his home in Ewhurst, Surrey to have a bit of a chat. Well, actually more than just a bit.

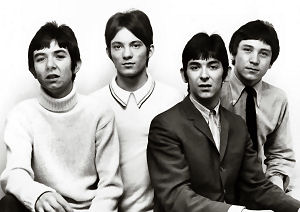

The Small Faces – 1966

Let’s roll the clock back to the Sixties. What was your attraction to drums?

A banjo! [laughs] I was twelve and a friend and I were washing a car for pocket money. We were fooling around throwing wet sponges and he popped his head up and said, ‘Let’s form a skiffle group.’ I went, ‘Yeah, great!” I then asked him, ‘What’s a skiffle group?’ He said there’d be one on TV – back in the days of black-and-white – so off we went, and sure enough this skiffle group came on at 6:30. It was one of the biggest stars of the day, Lonnie Donegan, and he was playing ‘Rock Island Line’ and ‘My Old Man’s A Dustman’ [laughs]. He was playing banjo and I went, ‘WOW! What a great sound.’ And it made a sort of drumming sound: I fell in love with it instantly.

Next day we went to a pawn shop next to Bethnal Green station. I’d seen a banjo there a few days earlier, so I dragged my mates over to buy it with no money in our pockets [laughs]. We didn’t think about that… it never crossed our minds.

When we got there, there was no banjo. The bloke had come and paid for it and taken it back so we left. My friend could see that I was really upset and said that a friend of his has a drum kit which sounded great to me.

And was it what you expected?

It turned out to be a floor tom and an old bass drum with no pedal. There were two sticks and one was broken in half [laughs]. My dad was a bit of a carpenter so we went up to his shed and found some glue – now this was before Superglue – and glued it together. I was impatient waiting for the glue to harden, so I picked it up and the end fell off. That happened a few times.

So we ended up banging this floor tom with one and a half sticks. My mother, who was walking home from work, heard the noise and wondered where the sound was coming from. The closer she got, the more she realised it was coming from her house. She threw us out! [laughs]

The Faces

It sounds like drumming found you.

I must have been subliminally influenced by my Uncle Dave, a mace thrower. He led a marching band and they did processions that went around the streets. I’d run alongside the marching band and pretend I was a side drummer because I loved that sound. After that I rushed back to my dad’s shed, which was like an Aladdin’s cave. There was a square biscuit tin there. I put it upside down, got two bits of firewood and started banging away.

After the banjo and one-and-a- half drumsticks episode, I found a shop called J 60’s in Manor Park. (Small Faces and Faces bandmate) Ronnie Lane would later buy his bass there and lived at the top of the road. I was thirteen when I went into the shop and asked if they had drums. There were a couple kits; one was a white Premier Olympic with calfskin heads. It was three drums and looked great. The cymbals weren’t terribly terrific and the bass drum pedal had a rubber ball for a beater. It was 64 pounds, 9 shillings and tuppence [laughs]. I said, ‘Right, I’ll have that!’ He said I would need some HP to pay for it. The only HP I knew was brown sauce. So I asked, ‘What do you mean HP?’ He responded with, ‘Hire purchase.’ I had to get ten pounds deposit and my mum and dad to sign the agreement.

I rushed home, but mum and dad were at work. Then I noticed her purse with a couple of tenners. I borrowed those and rushed back to the shop with the deposit. I then asked whether they could deliver. Yes, but they needed my mum and dad to sign the HP agreement.

Now you’ve got to remember that nobody banged our door after 5:00 PM. But at 6:30 PM the door goes and everyone panics. My dad opened it and this bloke walked in and said, ‘Where do you want the drums? I’ll put them in the front room.’ He just took over! Both dad and mum were looking at me with their mouths wide open, staring, giving me daggers. They were completely taken aback by it all and didn’t say a word.

So this fellow set these drums up in the front room and played something. ‘Have you played before?’ I had no other option than to tell the truth: ‘No, not really.’ So he said, he would show me something, but I had to get mum and dad to sign the HP agreement. I got more dagger stares from my parents. He got some brushes out, did that typical jazz swipe on the snare. Well, I’d never heard that one before! He held out the brushes, waving them and saying, ‘Now you have a go.’ I looked at my mum, my dad, the guy and the drums. Then I closed my eyes and had a go… and was actually doing it! I really surprised myself. According to my mum and dad, the look on my face was priceless. They had never seen me light up like that, so they signed the HP agreement and that was that.

How did things go once you had the kit?

That’s when the real trouble started: I was hooked. I would get up at 6:00 in the morning and play before I went to school. All I could think about in class was drums, tapping on desks and stuff. Then at lunchtime I would come home, get straight on the kit. At four o’clock I was right out of school and back on the drums again and didn’t stop playing until I was dragged off around seven pm.

This went on for about three months. I’d watch drummers on the telly and I remember going up the Shoreditch where there was a music shop… not one that sold musical instruments, but they sold sheet music. I bought some and got pictures of Buddy Rich and Joe Morello. Having had dyslexia, looking at the music was all I could do, so I studied the pictures to see how they were holding the sticks. And I would study bits of film and watch bands at the 59 Club in Bethnal Green. I saw The Tornadoes, and I was totally in love with The Shadows. From there I started to get into Booker T & the MGs and other soul artists. So it was mainly observing other players and listening to different styles, then miming what I heard. Putting that all together, I found my own style while teaching myself to play.

Do you recall any lighter moments during this learning period?

At one point I realized I was doing too much on the hi-hat and snare and thought, Hey, I’ve got these other two drums. So I started hitting them and found a whole new dimension. I kept everything fairly simple and remember learning a ‘mummy daddy’ (double stroke) roll from the sheet music. I went up there on a Friday and consequently every Friday. There was this drummer, Roy, and he was playing swing jazz. He was also a singer; I’d never seen a singing drummer before that. He had that old square Rezlo that came up in between his legs and he had his arms around it. I sat that there for three Fridays in a row, then this drummer, Roy, came up to me and said, ‘Are you taking the piss out of me?’ I asked what I’d done. ‘Why do you keep blinking at me? he asked. I was surprised: ‘I’m not blinking at you.’ He didn’t believe me: ‘Yes you are.’ Then I realised he had this affliction; when he played a beat he would blink at the same time, and when he did a drum fill, his eyes would flicker faster in time with that fill. So I said, ‘Because you’re blinking.’ [laughs]

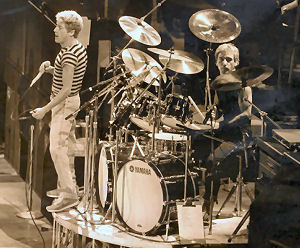

The Who

I then got to know him and said I was just picking up a few tips. When I went back the next week, halfway through the gig he announces, ‘We’ve got a young drummer who’s going to get up and play with us,’ so I thought; Great! Another drummer, I wonder who. Then he announced me! So I got up, sat there petrified… and I mean really petrified. So I’m behind his kit, a really nice kit, and I remember looking at these three other guys who look like giants. Everything then started to happen in slow motion. Wow! That’s when I broke ties with the earth. Years later I learnt to fly helicopter and that’s the only other time I’ve had that same feeling. I thought I was in heaven and really didn’t want to get off. And that was it, really; I was blooded… done!

After all that the barman came up to me, I was still shaking, and said, ‘That was great. Are you in a band?’ I said ‘No, I’m forming my own,’ to which he added, ‘My brother is just learning to play guitar. Shall I bring him round next Friday?’ Next Friday comes, and in walks Ronnie Lane. That’s how we met. He was a couple years older than me and was a plumber’s mate, while I was still at school. The rest is history.

Aside from the energy of the band, what attracted record companies to The Small Faces?

Don Arden [notorious manager and father of Sharon Osbourne]! We’d formed a band – me, Steve Marriott and Ronnie Lane – but didn’t have a name. We got this guy, Jimmy Winston (Langwith), in the band because his brother had a van, a police ‘meat wagon’ as we used to call it. Not only that, Jimmy’s parents had a pub, the Ruskin Arms in Manor Park, so we rehearsed there. The only problem was that Jimmy couldn’t play anything, so Steve had to teach him how to play notes on the organ and guitar – he wasn’t with us for long.

On stage with The Who

What was it like, trying to make the big time in the mid Sixties?

We decided we were going to be professional and played up in Manchester, at places like the Twisted Wheel. We would knock on the door and offer to play for nothing. Our van broke down in Nutsford and we were stuck there for a week whilst it got fixed. I remember that Ronnie Lane was half pissed and fell into the engineer’s pit in the middle of the night. We ended up in Warrington and hadn’t had a bath in a week! My hair had become a brown colour, which turned out to be rust from the inside ceiling of the van. Great times! [laughs]

We ended up in Sheffield and played at The Mojo. We knocked on the door and out comes Peter Stringfellow; it was his club. We were starving, so we said we’d play for nothing. He invited us in, fed us and watered us. We played that evening and brought the house down. A few months later we had a residency for six weeks at the London Cavern, just off Leicester Square.

Don Arden’s sidekick saw us there and invited us to Don’s office the next day. We said thanks, but no thanks. But after talking about it, the next day we did go up and that’s when we first met Arden. He looked at us – we’re all the same size, all small and cute… we looked the equivalent of four Justin Beibers, and Arden exploited that. We soon had a hit record with ‘What ‘cha Gonna Do About It’ and did ”Ready Steady Go”. Our first TV was ”Thank Your Lucky Stars”. That was the first time we’d seen each other on the television. I hid under the table and said to myself, ‘I don’t look like that!’

TV appearances quickly became a way of life, and by that time we had bumped into Peter Stringfellow again. He was a hip mod who would warm up the audience before the bands played; you never saw him on the telly, but that’s what he did. We have a lifelong friendship with him even now, and I’ll never forget his kindness and generosity. [Stringfellow would go to become a celebrity in his own right, owning a number of major clubs]

When we met up with [former Rolling Stones Manager] Andrew Loog Oldham, we broke ties with Don Arden and moved from the Decca to Oldham’s new Immediate label. With Immediate we never had to go out of the studio, which was really fantastic, because that meant we had lots of time to experiment. That’s how we got phasing (introduced on hit single, ‘Itchycoo Park’). I remember Glynn Johns, the engineer, taking tape from the recording machine and looping it around a chair to get this effect on the drums, ‘cause we wanted something different. We were the first to do that and other interesting things.

One of the things we suffered from – not that we didn’t appreciate it – was were constantly plagued with the screaming girls. It was amazing, we were as big as The Beatles – four albums and approximately twelve hit singles between 1965 – 1968. We didn’t have monitors in those days and the screams were so loud you couldn’t hear yourself. We became competent players but could never shift that teeny-bop image. Eventually it got to all of us, though more to Steve. All we wanted was prove we were not that teeny-bop image that had been created for us and exploited by Don Arden. We wanted an image like Jeff Beck or The Yardbirds, ‘cause we were always going to see them.”

How did the Small Faces end?

The last gig we did was at Crystal Palace. Steve wasn’t happy with the situation and threw down his guitar and walked off stage… we were left dangling. When you’re in a band, you’re mates and you become part of each other. You get some sort of telepathy going and share your emotions… the music becomes an emotional experience. It’s called ‘feel’. You feel it together and that’s how you bond as a group. When that’s lost or one member goes, it leaves a big hole. Steve was like a brother… it was like a marriage break up. He left and joined a band being put together by Peter Frampton called Humble Pie, which went on to do really well.

On stage with The Faces

But you, Ian McLagan and Ronnie Lane soon resurfaced as The Faces.

Yeah. In those days the Rolling Stones had a warehouse in Bermondsey Street just over Tower Bridge. The basement had a soundproof room where they stored their equipment. Mick [Jagger] said we could use it, so every Friday we would jam. One day, Ronnie Lane brought along his new neighbour from Richmond, Ronnie Wood. Ronnie and Rod Stewart were playing with the Jeff Beck Band, both on wages, and we thought that was a great band. Woody was playing bass, and I’ve got to tell you, he’s a phenomenal bass player. Well, he wanted to play guitar and step away from bass.

I’ll digress slightly, but I have to tell you that this was what happened with Ronnie Lane. He had an old Gretsch guitar but wanted to play bass. That experience of playing lead guitar is what made his bass playing so unique and melodic. He was certainly one of the finest bass players I’ve ever worked with.

Okay, back to the story…

Well Ronnie Wood joining the band filled that guitar gap. The following week he brought down his best mate, who was Rod Stewart. Rod sat on the amps watching us. This went on for a week. What would happen was we would have a break and go to the Bermondsey Arms and have a few lagers… a bunch of great guys hanging out together. Then we would go back and play a bit more. One day we thought we should put something together instead of just jamming about. We needed a singer, so everyone started singing… all of us would have a go. Ronnie Lane sang, but after Steve Marriott, who had such a big voice, Ronnie’s wasn’t strong enough. I went up to Rod, bought him a drink and asked him whether he wanted to join the band. He said ‘Wow! Do you think everyone would let me?’ I didn’t tell anyone at the time, but announced the news to the band when we went to [Ten Years After guitarist] Alvin Lee’s house for drinks. And it didn’t go down well. The lads didn’t want to experience what had happened before, what with the singer quitting and leaving us. But me, I saw it as the difference between success and failure, and experience was telling me that adding Rod would make that difference. In the end I got my own way.

Kenney’s first kit – Premier Olympic in white

Though Ogden’s Nutgone Flake was never performed ‘live’, you have been working on an animation based on the album, correct?

Yes, we’ve just been working on the script again. We had one but threw it out. One of the guys at Metro Goldwyn-Meyer once said that when you’re working on a film you have to get three things right and they’re the story, the story and the story. You’ve got to know it’s right and if there are any doubts you have to go back and make the appropriate scripting adjustments. New characters have to be created and that’s quite challenging. I said years back that this would make a great cartoon, and having lived with it for so many years I now have to finish the blinking thing!” [laughs]

What was it about Al Jackson, drummer with Booker T & the MGs, that was so relevant for you?

The one thing I loved about Al Jackson’s playing was that he was very simple in his approach; he knew his place and because of that, his playing complemented the rest of the band so much that you wanted to know more about guitarist Steve Cropper and the rest of the guys. Al made everyone shine through. Now some people think that if you play simply then you won’t shine through, but you do shine. Al also played just that little bit behind the beat, which was perfect. What listening to Al taught me was that the drummer should know his place in the confines of a band… know how to serve the band and the song.

How did you discover yourself as a player?

Over the years I’ve learnt is that you can discover yourself, your own style, through your instrument rather than through other people. Influences are good, but don’t stray away from your focus. You need to find your strengths and style from yourself; that should be the first and foremost thing. Then you let new techniques complement your style.

Now back to The Faces: How did the collaboration with Simply Red’s Mick Hucknall transpire?

The PRS (Performing Right Society) wanted to present an award to The Faces – to the band, but it also awarded to each member individually – at the Royal Albert Hall. In its seventy-five year history there had been only two other recipients of this iconic award: Paul McCartney and Andrew Lloyd-Webber. I called Rod and told him everything and he said, ‘I love an award, I’ll be there, you can count on me’. Anyway, Rod’s management then got hold of me to say that Rod couldn’t make it ‘cause he’s cutting a record or something. Basically he got his dates mixed up.

So we called PRS and explained the situation, but they insisted they wanted us there for the award and to do three songs. Andy Fairweather-Low, Paul Carrack and Mick Hucknall were also on the bill, so it ended up that Andy did ‘Ooh La La’ , Mick did ‘Stay With Me’ and Paul did ‘Cindy”. Mick was really up for it ‘cause he had always been a passionate fan of The Faces. He did ‘Stay With Me’ because it’s one of his favourites. That’s how we got together with him. Actually, having Mick onboard is great, but we’re still looking forward to doing something with Rod at some point. In fact, we all got together recently… Mick , Ronnie, Rod and myself, funnily enough, all met up and went to watch Bobby Womack performing at Jazz Cafe, who has also been a lifelong friend – we all get along as pals. No one is shunning Rod. Mick is just standing in and we’re enjoying it ‘cause we want to play… we don’t want to wait. Rod understands this.

In 1985 you and the Who played to what must have been your biggest audience which was ‘Live Aid’. Any thoughts on that?

I joined The Who back in 1978, three months after Keith Moon died, bless him. We were no strangers to massive gigs. It was an amazing experience for more reasons than just playing there. The excitement and the prestige of being able to take part in such a glorious event was really amazing for me. We had twenty minutes, and in the middle of ‘My Generation’, when Roger got to that part of the song that goes, ‘Why don’t we all f-f-f-fade away’, the satellite blew up and we did fade away as we were off air for a few minutes[laughs]. The viewing audience saw us disappear in the middle of ‘My Generation’, missed the whole of ‘Pinball Wizard’, and it all came back on the next track, ‘Love Reign Over Me’. It was great and you have to remember that they were stretching technology to its limits at that time.

The 26′ Paiste ride from Drum City

Any really memorable highlights that we don’t know about?

The indulgence for me at the time was that I learnt to fly a helicopter and co-owned one with (singer) David Essex. So that day I took off from my back garden and flew to Battersea, to meet up with two helicopters, Live Aid 1 and 2, and was asked to co-pilot one of them to the playing fields just outside Wembley Stadium. From there we went on to meet Prince Charles and Lady Diana. For me, that really was an unforgettable experience.

You pioneered the big drum and big cymbal sound favoured by the likes of John Bonham and Jerry Shirley. Where did that come from?

One day I walked into Drum City in Shaftesbury Avenue and this guy said Paiste had sent something for me. The lads in the shop had never seen a cymbal like it. It was 26 inches… a 26” ride! It had such a big sound and such a great bell that it became one of my treasured possessions. When I first got it I did a track called ‘Rollin’ Over’ [On ”Ogden’s Nutgone Flake”]. Since then I really look for that big sound in other rides. But it was mainly the Small Faces that led me to experiment with cymbals and drums. I had a great band, we had a lot of studio time, and I had a mixed bag of cymbals, some Paiste, some Zildjian. I always had a smaller crash to my left and even used a chinese cymbal there – Charlie Watts does a similar thing – but it became overpowering and I realised I needed sweeter sounding cymbals. You experience different things in studio sessions and those moments make you want to experiment.

The sticks you use are shorter than the standard drum stick, why’s that?

I use Vic Firth sticks but I’ve always sawn almost an inch off the ends of mine. Over the years drummer friends have said my stick should be longer. I never forget buying longer sticks and it would get stuck in my sleeve. If you find the centre of gravity if gets caught up your sleeve. I obviously found that I like a short stick and I find that I could be more snappier with them. For me, a longer stick has a bigger arc which also slows the speed of my playing.

I didn’t know until sometime later, that it’s not only me that does it but Phil Collins also uses a shorter stick. We use exactly the same length stick, I didn’t know that and neither did he. Weight wise, he uses a thinner stick and mine’s a bit more beefier, a cut down version of a 2B; Vic Firth kindly get them made for me and they are well balanced.

The Faces in 2010 with guest vocalist Mick Hucknall

What about technique and other changes?

Techniques change over the years, and whilst I had my sound with the Small Faces, when it came to playing with The Who, well to start with Keith Moon didn’t have a hi-hat; he just rode the left cymbal [laughs]. I did play bigger drums, though not any more, mainly because drums nowadays are louder and are better made. I still have all my kits and when I look at them I wonder how I played them. The kit I use now is a Yamaha. In fact, I just found out that I am the longest serving Yamaha drum endorsee, going back to about 1972, which is incredible. Before that I had the Premier and the Ludwig. With your polo club keeping you busy, are there future plans, especially the Jones Gang?

With The Jones Gang, there is talk of cutting another album. Besides owning the polo club there’s the animation of Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake and a Kenny Jones app I’m working on. There’s also a book that I’m working on which will be out next year. I’ve got a lot going on to keep me busy and it ‘s all quite testing, but life’s treating me pretty good.

What advice would you give an upcoming drummer.

Ask yourself: can I live without money and fame? You’re likely playing ‘cause it’s something you like and it makes you feel good. In turn, if it makes others feel good, that’s a bonus. Get that right and you’ll be playing drums honestly, which is the difference between successful musicians and those who fall by the wayside.

On the business side there are people you can go to for advice. The Musician’s Union are a responsible body of people and a mine of information. In my day, bands were being ripped off left, right and centre, but today you have many avenues to seek information. I know I had to learn how to negotiate and what to charge for a session. Then later, when I made a name for myself, I stopped the hourly rates and started to charge a fee. The thing is to always be fair. There have been times when I would do a session for nothing, purely because I was earning money in other bands and could afford to. The main thing was I wanted to do those sessions and play different music and work with different musicians. It was fun and part of my learning curve.

And finally, don’t sign any contract without first having it looked at by a suitable lawyer. The Musicians Union and even the PRS can be very helpful.

And with that final response Kenney’s mobile rings and it’s time for him to get stuck back into his day. He’s a long way from his days with the Small Faces, but there is no denying that the drummer who delivered the big sound behind the band is as keen and vital a player as he ever was.

Remo heads, Vic Firth sticks

Endorsements:

Drums: Yamaha

Cymbals: Sabian

Hardware: Yamaha

Heads: Remo

Sticks: Vic Firth

Others: BumChum, Kickport

Interview: Jerome Marcus

Editing Credit & Introductory Text: Wayne Blanchard

Photography: Kenney Jones

Additional Photography: Jerome Marcus