Mark Brzezicki’s is one of those drummers whose playing is instantly recognisable. A busy musician reminiscent of Ginger Baker and Keith Moon, Brzezicki’s wealth of dynamic grooves propels songs but never detracts from them. And his aural assault has won him many friends, allies and people eager to have him play with and for them. His session CV is impressive and he has played with the best bass players in the world.

Mark Brzezicki’s is one of those drummers whose playing is instantly recognisable. A busy musician reminiscent of Ginger Baker and Keith Moon, Brzezicki’s wealth of dynamic grooves propels songs but never detracts from them. And his aural assault has won him many friends, allies and people eager to have him play with and for them. His session CV is impressive and he has played with the best bass players in the world.

“I still aspire to be a good drummer,” he smiles. “That never leaves you. I didn’t go away to learn in a particular way, I guess I probably came up with my style by default.” Brzezicki is best known as the engine room of Big Country, which celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2007 and is currently working on a new album, sadly minus the talents of frontman Stuart Adamson, who committed suicide in 2001.

In many ways you sense it is a romance being played out by Brzezicki and his fellow Big Country alumni, bass player Tony Butler and guitarist Bruce Watson. Butler’s busy bass playing perfectly complements the energetic drumming, while Watson changes from sparse chord stabs to melodic harmonies on the guitar. The sum of the parts is greater than the individual constituents. “We all play for the song,” remarks Brzezicki. “That’s what is most important.”

Inspired by Phil Collins’ playing on the Brand X album Unorthodox Behaviour – “It came at me like a missile. It was one of the biggest things that ever happened to me. It’s still my benchmark bible.” – Brzezicki’s started to develop his own unique style. By the time he was playing gigs punk was happening and despite loving the work of the classic drummers like John Bonham, Moon and Simon Phillips, as well as Collins, Brzezicki was also picking up on new contemporaries, like XTC sticksman Terry Chambers (“I loved his tom approach”). “I always feared that I was too busy,” he says. “But people have booked me for sessions and told me to “play like Mark”. That’s been nice. I’m pleased how I’ve been able to maintain my own style.

“Steve Lilywhite (Big Country producer) really liked the fact I was coming up with new ideas. He told me “I love what you are doing, Mark, let’s give it more of the same character.”

Building up an impressive CV with other artists saw Brzezicki always ask how they wanted him to play. The confidence booster always came with the answer “like you always do”. Modest about his own talents, you feel Brzezicki was slow to realise how good a player he was, and remains today. “I guess people were booking me because they wanted what I could bring,” he shrugs.

“I quite like playing fills over two bars. Nobody was doing that when I started. For me it’s about interesting rhythms. I was always torn between thinking “was I overplaying?” or just being myself. “I pride myself on being a song drummer. The song is what makes me play the way I do. I always try and play for the song.”

Brzezicki’s education on the drums is a fascinating one, from his first taps on a neighbour’s Gigster-style kit, to his first odds-and-sods big kit, to buying an ex-London Transport van and driving off to laybys with his kit set-up in the back for somewhere to play. Coming from a musical family helped. His two brothers are both musicians and it was a purchase of a bass guitar and guitar for them as children that stirred something within him. “The chap across the road had a little drum kit in his garage,” he remembers. “It was a Gigster and to be honest I was always over there looking at it. It was aquamarine sparkle and I was mesmerised by it. When I started tapping away on it, he said I was better than he was. I saved up all my money from my newspaper round and bought it.

“My next kit was a whole mixture of drums. There was a Beverley tom, a home-made floor tom and a bass drum that is now my coffee table.”

“My next kit was a whole mixture of drums. There was a Beverley tom, a home-made floor tom and a bass drum that is now my coffee table.”

His musical education came when he joined a jobbing covers band. “I saw them and thought they were fantastic. They were doing Steely Dan stuff really well, the Commodores. I had to learn the top ten every week. They were doing corporate gigs, everything, and I had to learn how to play these powerful songs quietly. I had to control my volume. It was a great lesson.” An audition with a prog rock covers band through Melody Maker saw him paired with Butler for the first time and also sent him on an exciting musical road trip. The band became On The Air with guitarist and vocalist Simon Townsend, brother of Who legend Pete, and was signed to Warner Brothers. As punk hit, the would-be prog rockers suddenly turned to The Clash, The Jam, XTC and Brzezicki’s powerhouse sound attracted Townsend senior, who enlisted him to play on seven of his solo albums.

“There was a 1979 Right To Work march and The Pete Townsend Band was headlining the festival for it. I was playing all these Who numbers and his solo stuff. It was terrific.” Suitably impressed, Who bass player John Entwhistle also summoned the young Brzezicki to jam with him, and Roger Daltrey enlisted him for two albums. Meanwhile, Brzezicki and Butler – Rhythm For Hire – got a call from Ian Grant, a manager who had just put Adamson and Watson together to write songs. “We signed a deal with Phonogram and did some demos in about 1981 and 1982. We recorded the first album, The Crossing, at RAK Studios.” It was a big hit. The album yielded several chart hits, including In A Big Country and Fields Of Fire. Big Country had arrived.

So had Brzezicki. “I became the in-house session drummer at RAK,” he recalls. “Suddenly I was working with a whole load of new artists for producer Micky Most, people like Suzi Quattro.”

The follow-up album, Steeltown, saw Brzezicki become more confident, and experimental. On one song, Tall Ships Go, his snare broke and he spotted a metal ashtray “about snare height” and started playing that. The homage to heavy industry also saw him play a fire extinguisher and use anything on hand to get the right sound. “On Tall Ships Go I had these octobans, Copeland-like, above the hi-hat and instead of playing 16ths on the hi-hat I would keep hitting the octobans. It was a different sound and feel. It worked for the song. “I would always take too much into the studio. And I don’t care about snare buzz. I like everything to rattle and squeak to the movement. I love the 1970s and the 1970s drum kits, the big kits with lots of toms. I love going around the toms. You play differently.”

Steeltown was another hit album with several hit singles. Big Country’s star was rising, and with it Brzezicki’s. There were other calls on his time. He joined The Cult as they hit the big time with songs like She Sells Sanctuary, and he also got the call from Midge Ure to take up drumming duties with Ultravox, following the departure of Warren Cann. Again, this was the start of a musical relationship with Ure, with Brzezicki getting asked back to play on the Scotsman’s solo output, too. But it was another learning process for Brzezicki, paired with legendary German producer Conny Plank for the first time. “I did the U-Vox album with Ultravox. I turned up with five rack toms, a gong bass, a multitude of snares, lots of cymbals, I had all kinds of stuff with me. Conny had never recorded drums in his life before. I went to see his control room which tiny and had four faders which moved the other way.

Steeltown was another hit album with several hit singles. Big Country’s star was rising, and with it Brzezicki’s. There were other calls on his time. He joined The Cult as they hit the big time with songs like She Sells Sanctuary, and he also got the call from Midge Ure to take up drumming duties with Ultravox, following the departure of Warren Cann. Again, this was the start of a musical relationship with Ure, with Brzezicki getting asked back to play on the Scotsman’s solo output, too. But it was another learning process for Brzezicki, paired with legendary German producer Conny Plank for the first time. “I did the U-Vox album with Ultravox. I turned up with five rack toms, a gong bass, a multitude of snares, lots of cymbals, I had all kinds of stuff with me. Conny had never recorded drums in his life before. I went to see his control room which tiny and had four faders which moved the other way.

“He was great, though. He said “okay, we have to mic the drums, but I don’t think I’ve got enough mics. How do you do it?” It was a lot of fun.”

Getting the call for Midge’s solo career saw Brzezicki paired with Level 42 bassist Mark King and his bass playing brother Steve. “Midge is a fantastic musician. I was really freed up by him to just play.” Through Ure, Brzezicki got the call to play for the Prince’s Trust concerts and was suddenly playing drums with Phil Collins. “That was amazing. We used to warm up together at rehearsals and I’d say “do you remember this from Brand X?” and we’d both go for it. I’ve been very lucky. “I was part of the Prince’s Trust house band for seven years, did the Mandela Tribute Concert and Party In The Park for four years.”

Lucky? Maybe not. Collins was suitably impressed to recommend Brzezicki to former Abba vocalist Frida for her second album (Collins had played and produced her first). But Brzezicki remains the reluctant hero. “I still have that innocence in me, I guess,” he says. “I’ve still got that feeling that I haven’t arrived, that I still have to prove myself.” Other’s faith in Brzezicki to nail the part was further confirmed when he got the call to join Procul Harum back in 1991. He was initially summoned for an album session and then recruited into the band going back on the road. “What was really weird is that BJ Wilson was a great drummer and has a lot of fans. I had to doff my hat to him with my playing, but Gary Brooker, Procul Harum vocalist, was keen for me to be myself. It was half making sure it was like me and at the same time I did a bit more research into Wilson’s playing style and how he would play songs.

“There was also the orchestral side as well. I worked with the Halle Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra and Edmonton Orchestra, for example. It’s very demanding playing with an 85-piece orchestra. It really challenges.”

When Adamson died it appeared the wheels had fallen off Big Country. “It knocked everyone for six. I was very lucky because I’d been keeping the Procul Harum gig running in tandem with Big Country. I kept myself busy. That helped.” The band played at the tribute concert to Adamson, but Butler had quit the music business to become a lecturer in the West Country. Coaxing him out of retirement was a difficult job, says Brzezicki, but ironically, it was Butler himself who laid the foundations for the band’s return. In between time, Brzezicki had revived history to link up with Townsend Junior again for the Casbah Club, also featuring Bruce Foxton, of The Jam and Stiff Little Fingers, on bass. “Tony rang to say it was his wife’s 50th birthday and he was putting together a band and would I like to go down and play drums. I went down to Launceston, Cornwall, and played and it was just great to be playing together again. He said why don’t we do something, and here we are.

“We’ve got seven songs laid down and another five or so to record. We’ve played a few undercover shows and the fans love it. We all do a bit of singing, including me, and the reaction has been amazing. It’s a very emotional trip.”

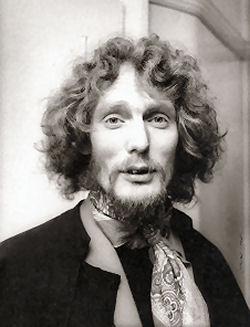

Interview: Mark Forster