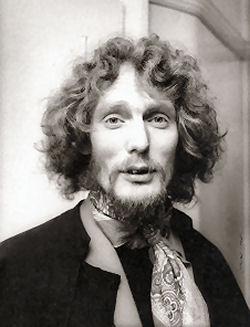

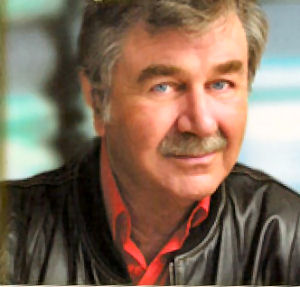

Pete York phoned from his home in a snowy Germany and I got the chance to use my new-fangled phone pick up to record his every word. I’d just returned from skiing in Italy and as typical Englishmen our talk immediately turned to the weather.

Pete York phoned from his home in a snowy Germany and I got the chance to use my new-fangled phone pick up to record his every word. I’d just returned from skiing in Italy and as typical Englishmen our talk immediately turned to the weather.

So how is it in Germany?

“We had a lot of snow but it started to rain today so it’s beginning to wash away but there’s a lot to wash away down here in the South, we always have piles of snow.”

Do you do anything of a sporting nature living so close the snow?

“No I don’t. I started many years ago to try and learn and it was going ok but its hard, you live here and the mountains are just an hour away but getting myself round to actually doing it, going down there and going through all the performance I don’t do. My wife had lessons as well but we never really took it so far. Now I’m getting to this point where I found out that my bones are quite breakable then I think it’s probably a bit dodgy.”

Only if you fall

“Yeah only if I fall, but then again you think positive.”

What got you into drumming, why and when?

“I started when I was about 8 years old. We had one of those brass bells that you would have in a hotel reception. You’d push the button on top and it would go ‘ping’ and I thought this was terrific. When I was a kid I used to have the radio on and bang on this with a couple of pencils so that was my first attempt at drumming through listening to the radio, listening to lively music that we had then, bearing in mind this was 1950. So what was to be heard was probably the Billy Cotton Sound Show, Jack Payne, that sort of thing which was lively music. I was really conscious of the entity that was American Jazz at that point and of course there was no rock’n’roll. There was lots of music on that was a hangover from the Sinatra times, the late ‘40s.”

Then the jokey songs of course

“Yeah, but when I heard songs with rhythm I enjoyed that. Then I got the little toy drum with the short drumsticks, so by now I’m probably about 10 years old, not knowing at all what I was doing, just doing it for the fun of it, driving my parents crazy. Then I think by the time I was about 12, I used to save up my pocket money for everything because my parents wouldn’t buy me a drum set, or bits of it either so I had to save up. The first proper snare drum I had cost me about £3 and it wasn’t very deep, about 3″ or 4″, one of those no-name things.”

Did you buy it from Yardley’s in Birmingham?

“No, we were in Nottingham at the time. The shop on the corner up in what they call Theatre Square which had the Theatre Royal and The Empire, where I actually saw at the age of 9 or 10, Laurel and Hardy live which made a great impression, I must say, because now I love these people. I didn’t really know what I was seeing then. They were touring the English theatres to make a bit of bread in their old age, rather sadly. They were of course much loved and when you read in the books how they were received over here on the theatre tours its very heart-warming indeed.”

So this was the 60s?

“Yeah. In the 50s I went to a boarding school where you did military training so part of it was CCF (Combined Cadet Force). I immediately joined the band because of course there was the chance to play a drum and so I learned from the band master, who was an ex-Royal Marines band Master. I learned the rudiments in so far as singles, doubles and paradiddles, the other rudiments they weren’t really interesting for the military drum figures, but I started to learn those probably when I was about 13. That started me off on the things I was going to have to practise to play cleanly and so on.”

Where was the school?

“First of all it was Nottingham High School for a short time which was a day school and then I went when I was 14 to Trent College which is between Nottingham and Derby in a town called Long Eton.

The school had a jazz club and if you remember in the middle 50s two movies came out which we all went to see firstly, The Glenn Miller Story and secondly, The Benny Goodman Story. Gene Krupa was in both of them in glorious Technicolor. His scenes, which were quite short, made an incredible impression on me. First of all in the Jazz Club where he’s playing with Louis Armstrong where James Stewart as Glenn Miller sits listening to him, and the other one, The Benny Goodman Story, he had a bit more to do even a couple of lines of dialogue and of course the famous scene in the Carnegie Hall sequence. It was great, absolutely wonderful.”

Were you playing jazz by this time?

“Yeah, well playing what I thought was jazz. What I liked at that particular time. I think fairly early on I got the difference between what the Brits were playing in terms of jazz bearing in mind in 1954 or 5 you had Chris Barber and all of them beginning to come up then. There were big bands of course, I remember buying Ronnie Verrell’s version of Louie Bellson’s Skin Deep with Ken Macintosh when I was about 12 or so.”

What stopped you going to University?

“I don’t know whether it was anything to do with money from the family but my dad was in the iron and steel business and he thought he could help me if I went into that line. I had no idea what I wanted to do. I wanted to be a musician but I thought forget it, that can’t happen, so I knew I was going to have to work. Dad said he could put me in with this company in Birmingham, do an apprenticeship there and have a good solid career; that was all it was about in those days.”

When did you actually start playing semi-professionally?

When did you actually start playing semi-professionally?

“My first gigs were in Birmingham, I went there at age 18, started my apprenticeship and one of the people who I sat with in the office learning the things I had to learn, knew the sister of a jazz trumpeter who had come up from London University to do a course at Birmingham University. He’d been a fairly successful jazz trumpeter on that student scene down in London according to this guy who’s sister knew him, his name was Eddie Matthews. He was a good player and he was looking for people to join his band, I went round to see him and introduced myself with my ram-shackle drum set which was a right old mix of stuff and then we played together and he asked me to join him. We had a quintet and at one point we had a septet as well. It was the quintet which was really quite good, and bearing in mind the influence at this time were of course the mainstream influences like the Basie Band. I’d seen them live in 1957 with Sonny Payne on the drums, a couple of years later Ellington came over and I saw Sam Woodyard. But small group people who were really beginning to make an impression on us youngsters were of course Cannonball Adderley, which was terrific stuff. I thought that was great. I could follow Charlie Parker’s lines and I thought what he was playing was absolutely terrific but there was a lot of other people who got into playing great streams of notes where sometimes I thought those lines missed the point.”

“So at that point Spencer Davis was at Birmingham University and he used to sing during the intervals in the jazz session. He’d come on with a 12-string guitar and a harmonica round his neck on a harness made out of a wire coat hanger and he’d do the sort of Donovan bit (but before Donovan) and then he would also sing a couple of songs with the band. When we were doing a traditional jazz number (we had a trad band as well, we’d do things like ‘Shimmy Like My Sister Kate’ and ‘C.C. Rider’ and all those old blues things) and he’d sing with us so we got to know each other. By the way, just digressing, this University quintet won the National University Jazz Band Competition and when we came back to Birmingham with the trophy they put us on local TV so that was my first time in front of a TV camera; that was about 1963. ”

Did Joe Morello have a big impact on you like the rest of us?

“Very much, funnily enough I went to a clinic at Digbeth Civic Hall, where the headquarter of Birmingham Jazz Club was, with Joe and in the same house on that night were The Honeycombs with Honey Lantrey playing drums in another hall in the same building. Of course she played beautifully.

From very early on I realised the Americans had a way of moving the sticks and sitting at the drums and playing which I wasn’t seeing too much of amongst my contemporaries. I was desperate to find out really how they did it, that American way of playing, it seemed so efficient for one thing.”

Are we talking about the side to side movement here?

“I can’t think of anything more than, I was talking to Butch Miles about this many, many years later and he said “you can tell a good drummer if he looks as if he’s dancing on the drum”, as if there’s this fluid dancing movement around. The movement is somehow flowing and efficient. When you say sideways what do you mean?”

I meant a circular motion really

“That’s right, when you did the roll Buddy used to say… or actually it was Louis Bellson who actually talked about these things in his clinic, they’d call it the whipped cream roll where the hand went more in a circle when it played that really great orchestra roll.”

Of course the thing which you and Buddy have, which I spotted last time I saw you playing, is the economy of movement, where the ride cymbal is in a line with the other elements, you don’t have to actually lift your wrists up beyond a comfortable position.

“Exactly. Buddy started to come over in 1966 with the Big Band and knocked everybody sideways and at that point he was playing Rogers which I was also playing. He came over at one point during those years and did a clinic in Shaftesbury Avenue, The Dominion, further up towards Edgware Road there was at one point a ballroom and they got Buddy doing a clinic in there and because his drums were on the road for the concerts. Of course Rogers drums were making them up in England, they sent the parts over from America and built them up in England. So they made up a kit for him to his specs which were the 24 x 14 bass drum, and the two 16s and the 13 and the cymbal arms in the place where he had them and he played this one clinic on that set and then it went back up to Edgware because he was off on the road with his own stuff, his American Rogers. So I immediately jumped in to Ken Spacey [who ran Boosey and Hawkes] and asked what’s happening with that kit and he said “I don’t know what they’re going to do with it, sell it or something” so I said “well can I have it?” (because I was big with Spencer Davis in those days) and he went “yeah”.

And you were a Rogers endorser weren’t you?

“Yeah.”

There’s a strand on Mike’s website from time to time about English Rogers. You were an endorser weren’t you?

“Yeah.”

Did you ever endorse American Rogers?

“I had a kit of American Rogers which I bought from a drummer friend from Birmingham called Lionel Ruben, Lionel helped me as well. I’d go in the shop and we’d talk about stuff and he’d help me with my hands. The most help I had in that Rogers period was in 1970 when Roy Burns came over. [Roy Burns now manufactures Aquarian heads.] He came over as a staff clinician for Rogers and he was going to be doing about 3 weeks around England, the glory days of clinic tours. I said to Ken Spacey who was in charge of everything then that I’d love to spend some time with Roy and I had a big car then, I was on the back of my Spencer Davis success but still I volunteered to be his roadie, you don’t have to pay me anything, just get me a hotel room and I’ll drive him around and help him with the kit. I thought I really want to be close to this person and see him. I’d seen him before and he played terrific but he was doing all that Buddy stuff really, which we now know, you might say, is a classical American way to play. I don’t think it’s got much to do with the Moeller technique, in fact far from it. If people say Buddy had the most natural way of playing the drums as anybody then that was it, I thought if I can get with Roy for a bit he can show me how this works, which he did. I meet him every so often and I never fail to thank him. He says “well I never charged you for those lessons, Pete, but anyway it’s nice that you remembered me”. He’s a funny guy, lovely.”

So you were now playing with Spencer in the Spencer Davis Group?

“Yes, we were playing in a sort of amateur way around clubs and doing gigs and this is with Muff and Steve [Winwood].”

So what year are we in?

So what year are we in?

“We’re now in 1962 and we’re semi-pro. I’d done semi-pro jazz gigs since 1961 in Birmingham. I remember my first pay was 15 shillings and a bottle of brown ale! So I did lots of jazz gigs around the Birmingham area which were great fun. Then Spencer got this possibility to put a band into a place called The Golden Eagle in Birmingham every Monday night and luckily the band he chose to go in with him was me, Muff and Steve. Steve played piano almost exclusively at that point which he had done in his father’s jazz band but when he found Spencer’s guitar hanging around, he picked it up and of course within 5 minutes he could play it better than Spencer. I very much believe that Spencer never recovered from that, the fact that he found himself with this prodigy in the band who stole the thunder from him at every possible opportunity. Spencer simply wanted to be a blues player at that time and then this young guy comes in and steals all the thunder, he sings better than anybody and he just has it all naturally. Steve had this American thing going which he could do even with his fairly high voice then, we did a Big Band concert in Birmingham in 1964 with Johnny Patrick’s Big Band. We did those Ray Charles things and Steve sang them all and knocked everybody sideways, the maturity of his voice; because he had good music around the house all the time. Steve and Muff’s father was a dance band saxophone player but always around the house they had Coleman Hawkins and Ben Webster on the record player so he was always hearing good stuff.”

When did the man with the big cigar turn up?

“Well there were two or three of them and I always wonder whether we did make the right choice. First of all there was Giorgio Gomelski, then there was the guy from Decca, Mike Vernon, he wanted to have us and he probably would have been kinder to us than Blackwell was. Blackwell just came in and saw the name by chance and immediately fell in love with Steve and I mean that most sincerely.”

So we’re talking Chris Blackwell from Island records here?

“Yeah. So he signed us up but I think from very early on he saw that Steve was the main thing. Okay we were together as the Spencer Davis Group but he was going to have to ease Steve out of it at some point and when he did that there was so little consideration for the rest of us that I felt very bad about that. It was like ‘okay now I’ve got the boy I want it doesn’t matter about the rest of them’. It didn’t matter to Muff anyway because he didn’t want a band without Steve and Steve didn’t want him in his band because he had got his pals which were by then Jim Capaldi, Chris Wood and Dave Mason.

“The truth of it is there was definitely a division between the people who did drugs then and the people who just liked a drink. That in fact caused a divide, and because I didn’t smoke dope; I didn’t like the idea of that, it didn’t appeal to me, I smoked cigarettes, but the other drugs frightened the shit out of me because I’d seen and I’d read a lot about jazz musicians and I was in contact then with people like Phil Seaman and I’d seen what a state he was in and I’d see sometimes he could play brilliantly and sometimes he was crap and I thought well if that’s what it does to you, I’ll stay away.”

You were completely immersed in jazz but yet you joined what ultimately became a superior rock and roll band?

“That’s right. Nobody at that point, in the Spencer Davis Group minded the fact. When I played the Spencer Davis group it swung even when we played straight 8s. A lot of rock players will play straight 8s and they’ll give all the 8 notes equal value, but I never did. You could phrase it a little differently which I always did. I didn’t really work this out thinking that’s what I’ll do; I just did it that way. I never played solos then, not with Spencer Davis They sometimes gave me extraordinary material [to play] bearing in mind a regular Spencer Davis Show at [say] the 100 Club would include things like ‘Sister Sadie’. I used to do a couple of George Formby songs for a laugh. The show was really very entertaining.

You told me before that things didn’t end particularly well with Spencer inasmuch as, just like many other bands of the 60s nobody actually got the amount of money that they expected.

“Well we found out later, bearing in mind between the years of 1964; when the first single came out which was ‘Dimples’, and April 1967; when Steve and Muff left and Spencer and I had to reform, in those years we had five Top 5 hits and 3 or 4 Number 1, depending where you were, and also ‘Give Me Some Lovin’ was Top 5 in America, it may have been Number 1 at some point, but they were all big- selling records. We were on a deal where it worked out that Blackwell was getting from the people that he had done his deal with, he was the production company, but he was taking roughly speaking 6% for himself and giving 4% to the band, that’s 1% each, and telling us that that was the sort of deal everybody expected in those days. Because we didn’t know any better we just accepted it. We were happy, we just didn’t know. Also the other thing which was extremely lax of me was I didn’t realise how much the royalties, the mechanicals, were getting away from me, because I didn’t bother about getting my name on anything. If they put my name on anything I was like “thanks a lot guys”.

So you did contribute to writing the songs?

“Some of them I did and some of them they put me on because the rhythm was intrinsic, but on the records that have made the money, I’m not included on at all. Which is okay. They were all put together in jam circumstances really and who wrote the ridiculous words, I don’t know, but they never asked me to contribute anything, I should have done, because I was probably more literary than the rest of them. But I didn’t think about it and that’s how it goes.

So the first band breaks-up and then we put in a couple of other people: Ray Fenwick and Eddie Hardin. I carried on with Spencer for about another year and a half and we made more singles and by then the atmosphere inside the band was becoming strained. One thing that we did during Spencer’s shows at that time, was Eddie and I did a number with just organ and drums and it was an arrangement we’d hashed up and we had a drum solo in there and the whole thing lasted about 10 minutes and it was spectacular, so this would be about 1968, and we were doing this on our American tours and so on. Then when I decided I couldn’t take it anymore I left. Eddie suddenly said well if he’s going, I’m going, so he left as well. So Spencer then had to get in some other people who I think were Nigel Olsen and Dee Murray.”

“So, I’m out of Spencer Davis, I’m still doing little jazz gigs, but then we formed Hardin-York. Eddie and I got together a few months after we both split from Spencer for our various reasons, partly because we were getting fed up with him. He’s a strange old bird and getting stranger, he’ll probably say the same about me. That duo worked very well and really hit it big in Germany and our 3 albums we made, with Mike Hurst producing, they all went gold. Mike just told us this recently but as usual we’d fallen in with yet another villainous manager a guy called Mel Collins.”

Coincidentally he also managed Argent

“Did he? And Cat Stevens. And screwed everybody… I know, we always complain about these people, they probably had their own problems but we were so pissed off. We were down in Munich and we’d found out that Mel had been screwing us, taking money, left, right and centre, and we were going to try and find a way out. We were in Munich for several days and Eddie had a girlfriend down here and he wanted to go and visit Dachau, the concentration camp. I didn’t want to go so he went there, had a look around and found out that in the gift shop of all things, they sold postcards, forbidding postcards of barbed wire fences and watchtowers and so on, from Dachau. So he sent one to Mel Collins saying ‘Wish You Were Here’.

We spoke of payments I know you wrote the theme music for that children’s programme Magpie. Did you ever get paid?

“Yes. We got royalties for that. The royalties actually lasted for some time. They were quite useful, I remember when I got married to Becky she used to say where’s this money come from and I’d say it was an old TV series we did years ago. It used to pay the gas bill and things like that.”

How long have you lived in Germany?

“Since 1984, the thing is I often think what would have happened had I stayed in England, would I have been established on the scene there, would I have got into another big band, I really don’t know, but I can only say that since I came over here I’m been very well treated and I have done things I could never have done, I could never have done that ‘Super Drumming’ TV show anywhere else, nobody would have taken that in England but they did it with me here and it probably was the most creative period of my life. I can say I’m proud of as a body of work. It’s something I did which I think is a good thing to have done.”

Do you remember sitting with me and Ed Thigpen in a Chinese restaurant in Frankfurt? We all went out to eat with Remo Belli and Gary Mann I don’t know if you remember this but Ed had his stick bag with him which I thought it was a bit surprising and he opened it at one juncture and all the tines on the ends of his brushes were bent just like mine. I thought here’s Ed Thigpen, the greatest brush exponent in the World and he’s got bent wires on the end of his brushes just like me.

Do you remember sitting with me and Ed Thigpen in a Chinese restaurant in Frankfurt? We all went out to eat with Remo Belli and Gary Mann I don’t know if you remember this but Ed had his stick bag with him which I thought it was a bit surprising and he opened it at one juncture and all the tines on the ends of his brushes were bent just like mine. I thought here’s Ed Thigpen, the greatest brush exponent in the World and he’s got bent wires on the end of his brushes just like me.

“And now of course, Vic Firth makes a pair of brushes with bent ends, the Steve Gadd model. Vic gave me a pair, they’re alright, they’re more of a slappy sound but I don’t like them so much. I just like a good old-fashioned wire brush. I was surprised when Ed came on the Super Drumming Show and I think for some advertising reason he was playing a pair of plastic brushes which he gave me a pair of which I’ve still got. The tines were red plastic and the handle was black, I don’t know who made them but he gave me a pair.”

Calato?

“Yeah I think it was.”

Did you ever go to drum lessons?

“No, I never did. I used to go around to Lionel Ruben’s shop on the Ringway in Birmingham and just ask him things sometimes and I sat with Roy Vernon and we’d practise together and he’d correct my hand/finger positions and just show me how to operate the stick really.”

So you never learnt to read?

“Yes, I taught myself.”

Through the embarrassment of not being able to do it?

“Yeah, that’s right. First of all I got the book and then I thought ‘what the hell does this mean?’, and then I think it was Johnny Haynes helped me to understand the book. When I bought the Buddy Rich book; which I later found out was written by Henry Adler, he told me all about that. It was a case of necessity and then buying the Bellson book on syncopation which is a very good way to get to read lots of different note divisions, bar to bar, as it were, rather than repetitive things like 8th notes.”

“I think some of those old books are still classics, everybody says you can’t go wrong with the Lawrence Stone book. There are, I think probably 10 or 12 books from which you can get everything you need really. I started working on books and on the practise pad religiously, I would say, in 1966, after I’d seen Buddy, because the reason for that was simply (and it may have had the same effect on you) when we went to see Buddy whether it was at Ronnie Scott’s or wherever he was, queuing up and seeing everybody and his brother there in the queues outside, strange people you never expected to see, Dick Emery; what’s he doing there, people like that, but then everybody wanted to see Buddy at that time. I went to watch it like we all did and several friends opinions were ‘oh its impossible I’m going sell the kit or chuck it in the river’ and my attitude was ‘well you might not get there but at least you can try because if he can do it, it must be possible’. You just have to find out how, that was my feeling about it. I thought it was so magnificent what he played and the effect it had on the audience, the drama of it all, it was just magic. Did you ever meet him?”

Yes, he came into Drum Store and I have to say for some reason he was less than gracious, but it didn’t stop him being the greatest drummer ever. It’s a bit like Ginger Baker – that difficult geezer – he’s less than gracious too.

“Yeah, he’s the other end of the scale to Louis Bellson who was the most beautiful guy you could ever meet.”

Absolutely.

“I met Buddy twice and he was actually okay, he wasn’t nasty and the first time he was very interested. I’d seen the concert in Birmingham and went backstage and he was very interested to know what myself and my musicians thought of the band, how did it sound, what was the sound like, he was very interested in it all. I approached him completely around the corner because people had said don’t go in and tell him how great a drummer he is he already knows that, try and talk about something else which might amuse him, because everybody talks about the same thing. I went in completely differently and started talking about comedy and comedians because I knew there were a couple of comedians that he really liked like Robert Benchley the writer; Peter Benchley’s father, he was a very funny writer in the 40s and I bought these books of Robert Benchley and they were very amusing and when I met Buddy the first time my first line was I’ve got to thank you for turning me on to Robert Benchley, he said ‘what?’, then I elaborated and he was very pleased.”

Who else did he like, do you know as far as comedians were concerned?

“I think Don Rickles and Buddy knew each other quite well. After I’d been to America and seen him I became a huge Don Rickles fan and poor old Bernard Manning tried to do that but failed miserably because the people he was taking a pop at he actually didn’t like anyway, so then it didn’t work. Don Rickles had a pop at everyone but they’re all people who know him and they go there to be insulted. He would have a go at Frank Sinatra, all of them, and he’d have great lines about them but it didn’t matter because they were all pals and it’s a different attitude.”

(The interview was then interrupted by Pete receiving a phone call)

“That was the guy who runs a Chamber Orchestra which shows the variety of my life. One of the projects we’ve got going which we’re trying to sell is a Beatles programme with a little Chamber Jazz Group and 16 strings, which is lovely. What I would like to do is bring it all up to date.

Your first drum kit was a bitsa, so it would appear?

“Yeah, bits of this and bits of that.”

What else did you have?

What else did you have?

“When I got to Birmingham and started going out doing proper gigs it was a Premier. Then I bought an American Rogers from Lionel Rubin.”

What was Lionel’s shop called?

“Ringway Music. The set was from Cleveland it had the silver paint on the inside of the shells, I don’t know what that was supposed to do. Then strangely enough the Rogers thing all went wrong somehow with Boosey and Hawkes, they started selling a kit made at the Premier factory under the name of Beverley and then Ken Spacey who took over the Beverley said to all of us who were endorsing Rogers., “Right we’ve got to have your Rogers stuff back again, so we had to give it back, including the Buddy Rich kit. I should have bought it from them at the time but I didn’t think of it. Then these Beverley kits arrived. Me and Lenny Hastings played Beverley, Lenny was a great pal of mine, he had the American sound going on.”

He was an unsung hero wasn’t he?

“He was glorious. He could swing his arse off. I very much liked that small group thing in jazz, that Eddie Condon stuff. I liked George Wettling and Cliff Leeman, Dave Tough, tremendous, Lenny could do all that – none of the other trad drummers could.”

So you got to a Rogers kit then moved to a Beverly kit and next?

“Premier. By the time I went to the Chris Barber band in 1976 I was back on Premier. ”

Have you kept any of these kits?

“No. I’ve still got a Rogers snare drum 1967, metal, chrome over brass. The next kit after that was in 1979 when I changed to Pearl.”

Where you still are?

“Yes and I’m very happy with them.”

What are you up to now?

“What’s been a very good job for me now for 5 years is working with this German comedian, Helge Schneider and you can find lots of him on the internet, he’s very famous here in Germany. Sometimes we do 100 shows a year and he sells roughly speaking 2000 tickets a night. He’s a great musician, he’s a natural player, he can play anything, very good trumpet, very good sax and a super piano player, guitar, picks up anything.”

You’ve died and gone to heaven?

“Yes, because here I am with a comedian who makes you laugh all night plus we get to play nice music. He likes the kind of music I like, so there’s lots of swing in it. He lets me do the big drum solo every night; he gives me a great drum tech. His audience are all in their twenties but he is 55.”

He’s satirical?

“Actually he’s more whimsical, nutty. I used to say it’s more of a mix between Dudley Moore and Spike Milligan (and I can include Bill Bailey in this now), that gives you the sort of picture. It’s very funny, a two hour stage show and when you get to see this up close, I’ve stood in the wings with him sometimes and there’s 2000 people in the audience waiting and he says: ‘how do I start, what do I say first’ and I say ‘usually you say …’ and he goes ‘oh yeah, I got it’ and off he goes, but that responsibility every night when 2000 people are waiting for you to make them laugh. When we’ve got instruments and songs and arrangements we’re okay, we play them and go through them all and get the reaction but he hasn’t got a studied series of jokes, like a lot of them do. Theres a lot of comedians around today who haven’t got any real humour, they haven’t got funny bones, they’re not people like a Tommy Cooper who can just walk out there and people are falling about. Helge’s built this up, he’s been a star here for 20 years now, so he’s built it. We’re planning to do some jazz gigs again in the summer where we just go out and play.”

So Helge doesn’t tell any jokes?

“Well he’s funny anyway.”

He can’t help it?

He can’t help it?

“The thing is with him, we do funny things inside of the music, it can still be great jazz he’s playing but he’ll do something because he’s got a funny way with him and his physical movements are funny, also he plays great vibraphone too.”

I don’t suppose he plays great drums too?

“Luckily for me not that well. When I’m doing that amount of gigs with him which we are at the moment, it really takes care of everything in terms of I’ve got a good income. So the other things I do on the side all my other little projects I can just do the ones I want to do. I do a trio show where one of the presentations is a total Gene Krupa story, we do it in trio form just with tenor and piano and if you have very good people to play it sounds fine. Krupa had great trios.”

So no bass?

“No, you don’t need a bass if you’ve got a very good piano player, like Teddy Wilson, he was a master. You never noticed the lack of bass in the Benny Goodman Trio or the quartet, because of course the other thing that was happening is those old style drummers (and I still do this) they just feather the bass drum on four in the bar. There’s still a little pulse going on underneath there.”

There was some of that fours bass drum going on in Spencer Davis wasn’t there?

“Yeah, there was.”

And that’s what made it different?

“Yeah it was, you’re right.”

I’m assuming ‘Give Me Some Lovin’ was 4 on the floor?

“Absolutely, 4 on the floor all the way then all that drum feel which was not the original I’m sorry to say, it was pinched from another record. But of course was a really good simple interesting figure.”

They are the ones that work. Complications are not normally good, keep it simple I believe they say.

“What I should maybe do is send you a box, just for your own pleasure, of the Super Drumming DVD’s. They’ve just come out again and they’re now in a presentation box which includes backstage material as well. Maybe you can tell people about it. You can get it on Amazon all over the world but it’s just whether people know about it or not. I think it’s a great document and I meet young drummers here in Germany all the time, bearing in mind we did this 20 years ago, and they say ‘I started playing drums because I watched that show’. It’s really heartening.”

Remind me who played on them?

Well Louis Bellson, Simon Phillips, Ian Paice, Jon Hiseman, Nico McBrain, Zak Starkey, Steve Ferrone, Bill Bruford, Dave Mattacks, Trilok Gurtu, Cozy Powell, Mark Brzezicki, Billy Cobham….

I should have asked who wasn’t in the series!

Check out Pete York’s highly entertaining website on: www.peteyork.net

Interview Bob Henrit