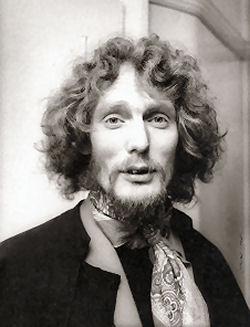

IT’S not a bad career high for a youngster who got into drumming using knitting needles as sticks. Woodstock, mother of all festivals, where Ric Lee and Ten Years After were one of the stand out acts. But don’t think the near-mythical gathering in a farmer’s field near New York defines the career of Mansfield’s most famous musical export, with apologies to Alvin Stardust. Lee, still pounding out Ten Years After classics with the ‘Now’ version, boasting three quarters of the line up at Woodstock, was one of a raft of drummers who inspired Spinal Tap, and also helped teach a young drummer from Redditch a few things about triplets.

That his love and enthusiasm for the music is still strong is testament to the enduring appeal of Ten Years After, the jazz-influenced blues rockers. He plainly still gets a buzz out of playing the music. It’s still a challenge, especially with new tracks being written and the arrival of Joe Gooch as front man to replace Alvin Lee (no relation). It’s about 50 years since the young wannabe drummer saved up his wages from a job delivering meat for the local butcher to buy a snare drum and stand that he had “idolised” for months – and that was it for a while. A young Lee, snare drum and sticks.

That his love and enthusiasm for the music is still strong is testament to the enduring appeal of Ten Years After, the jazz-influenced blues rockers. He plainly still gets a buzz out of playing the music. It’s still a challenge, especially with new tracks being written and the arrival of Joe Gooch as front man to replace Alvin Lee (no relation). It’s about 50 years since the young wannabe drummer saved up his wages from a job delivering meat for the local butcher to buy a snare drum and stand that he had “idolised” for months – and that was it for a while. A young Lee, snare drum and sticks.

“My oldest brother, Peter, had a wind up gramophone and all these 78s, like “12th Street Rag”, Guy Mitchell’s “Singing The Blues,” recalls Lee. “We wore those records out. I used to tap along to them with knitting needles. We also used to listen to Family Favourites and the Billy Cotton Band Show on the radio at Sunday lunchtimes. “Mum and dad said they couldn’t afford a drum kit so I got a job as a delivery boy for the local butcher.” With the 10 shillings (50p) a week he earned going into a fund for the much-prized snare – “I can’t remember the make now, but I’ve got a feeling it was an Olympic or Beverley with vellum skins” – Lee would tap along to the music on the radio or the discs.

Seeking lessons from a local drum teacher, the eager Lee was told “go and do piano for six months”. “It was actually brilliant advice,” he remembers today. “He also took me to several sessions and I learned to read music. It was good discipline. I had to learn to read music quickly because I had to turn the pages for him.” Cobbling together a 24inch gong drum for a bass, with an old hand painted Indian tom tom and Charleston cymbals, Lee soon immersed himself in the Mansfield music scene, often covering Cliff Richard and The Shadows, Elvis and other top bands of the day. Inspired by The Hollies’ Bobby Elliott, Lee sought further lessons and met up with another local drummer called David Quickmire, at that point occupying the drum stool in an up-and-coming band called The Jaybirds, then a three-piece with virtuoso guitarist Alvin Lee and bass player Leo Lyons, whose frenetic style masked a subtle touch.

Quickmire gave Lee an education in drumming and drummers, from Joe Morello, Bill Eyden, Shelley Manne, Buddy Rich and Art Blakey. “I also picked up on Gene Krupa,” recalls Lee. “Dave didn’t want the gig with The Jaybirds anymore. He wanted to get married and settle down. Unbeknown to me he had taught me the techniques that would get me through the audition.”

But after months of making a “phenomenal” amount of cash (for that time) through gigs – “I had been getting £15 a week with my first band The Mansfields.. At my day job with the Inland Revenue (I only worked there for a year!) I was only getting £7 10 shillings. When I joined The Jaybirds I asked for £15 a week and they said “yes”. I didn’t realise they weren’t making as much money as The Mansfields. “A few months later Leo came up to me and asked me to go for a split of the cash, not £15. He said that “when we make it, not if” I would still be on £15 while they were coining it in. I decided to take the split.”

Soon things were looking up for the band, but it was still a topsy-turvy road. Winning a part in the London show “Saturday Night, Sunday Morning”, saw them increase their earnings to £40 a week each and live like lords in swanky hotels. But then the show ended after just a six-week run and for Lee, it led to a hectic session schedule, taking over drumming duties from Clem Cattini at Southern Music, music publishers and others. A television appearance to bolster sales of tickets for the show led to them being approached by the agent for the Ivy League and things soon picked up for the band, now augmented by Chick Churchill on keyboards. Then fate played its hand and Leo managed to get the band, now called The Blues Yard, a slot at the legendary Marquee Club. “Blues was just happening. We had an interval slot on a Sunday supporting the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and we got standing ovations. “I felt the bass drum should work with the bass player and left hand with Alvin’s licks. We played at Middle Earth in Convent Garden and I was wrapping up my gear when two Brummies approached. One of them asked me what the patterns were that I was doing with my left hand, so I showed him. The two Brummies were John Bonham and Robert Plant. Bonham converted my left hand patterns to the bass drum, the famous Bonham triplet, although I think I had picked it up from Art Blakey or Max Roach.”

“Ginger Baker ….asked me if I had a pen, ripped up a fag packet and wrote down what he had been playing.”

Ginger Baker also showed Lee a few tricks after a performance with the Graham Bond Organisation. “He asked me if I had a pen, ripped up a fag packet and wrote down what he had been playing.” Woodstock came about for Ten Years After through London Records’ promotion of their albums in America. “We were starting to record tracks for what would become Stonedhenge and we got a telegram that we could play Bill Graham’s Fillmore West if we were ever in America.”

They duly did tour America, meeting up with The Grateful Dead in Phoenix, jamming with Jimi Hendrix and having blues royalty like BB King come and see them in New York. The three-day musical extravaganza in a farmer’s field near New York has acquired near mythical status and Ten Years After was one of the acts of Woodstock. Their energy and musical prowess won through despite technical troubles and rain that affected the festival. But Lee, whose powerhouse drumming propelled that performance, remembers Woodstock as a stressful few hours, with the band hungry and bewildered by the sheer scale of events. “Woodstock was fabulous,” he recalls. “It was different to anything that came before, or after. It was initially going to be a 50,000 people festival and we weren’t going to do it because we weren’t getting paid enough. “At that stage there were only about nine or ten acts. I don’t think The Who, Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane had agreed and the bill wasn’t that fantastic. It was a difficult decision.” Joni Mitchell, that siren whose music encapsulated the Woodstock era, was among the acts which declined to perform at the festival, along with Free, The Moody Blues, Led Zeppelin, Jethro Tull, the Jeff Beck Group and Frank Zappa.

Ten Years After, who had only just begun to get a reputation in America, did manage to slot the gig in during a hectic couple of days stateside, in front of an estimated half a million people. Lee remembers: “I think the figure has been inflated. I guess there were about 300,000 there, but it was still unlike anything we’d seen. People just dumped their cars and walked. You couldn’t get within six miles of the place. “We had flown in from St Louis that morning and then driven for two hours. There were helicopters for the acts and we went up this hill and were standing there waiting for our helicopter when these four geezers came up and got on in front of us. It was Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. “We hadn’t had anything to eat or drink. We were told not to eat anything that wasn’t cooked or drink anything that wasn’t sealed because of food poisoning and hepatitis. “When I look at the film now I realise how dodgy the sound must have been. After a storm passed through it became very cold. I had only got a tank top and jeans on and there are pictures of my first wife sewing different materials on to the tank top to keep me warm.” The band went on at 10pm on the last day. The storm had delayed proceedings and the atmospherics were terrible. “We started Good Morning Little Schoolgirl four times. It was a dreadful start in front of 500,000 people. However, we finished the set and managed to find a state trooper on a horse, and a car complete with driver to take us out of the site. We got back to base camp at about 1am, asked for something to eat but the restaurant was closed. Luckily, there was a diner nearby and I think we ate everything they had.”

“I think it is most important to play what the music requires.”

Getting back to New York later than expected, the group found their rooms had been let. They found alternative places to sleep before their New York gig and set off for Baltimore the next day. A truly whirlwind tour, with emotional highs and lows. “If we hadn’t have done Woodstock, we wouldn’t have had a career like we have,” admits Lee. “But in a sense it was just another gig. The enormity of it was that it was the first and last of its kind.” Ten Years After played the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970 in front of 600,000, although: “It didn’t have the atmosphere of Woodstock.”

At the height of their career Ten Years After released 11 studio and live albums, including the critically-acclaimed Cricklewood Green containing the UK Top Five single “Love Like A Man”. But the cracks were beginning to show. Alvin Lee and Leo Lyons weren’t seeing eye to eye and the drummer was often the middle man. “I was like the bloke in Spinal Tap, which I’m sure was based on me. I was the buffer between the two. That’s what I ended up being, on stage and off.” During the recording of A Space In Time, Lee had been ill and the band recorded what was to become one of their biggest tracks without him. He returned to the studio and the band asked him to dub the drums on to the track. In those days there were no click tracks, consequently the timing shifted throughout the track, but Lee enjoyed the challenge and believes it adds to the track’s feel. “I’d Love To Change The World” became TYA’s biggest hit in the USA.

The wheels could have come off the Ten Years After bus when Alvin Lee finally split for a solo career. By this time Ric had got involved in music publishing and then joined Stan Webb’s Chicken Shack before a brief reformation of Ten Years After for the Marquee’s 25th anniversary. Lee, who managed the band for an additional couple of European dates, said: “We also did Reading as “special guests”, which was nice. We went our separate ways again until 1988 when I got a phone call from Alvin again seeing if we could do some European festivals. It was good to get back together again.” A new album, “About Time”, recorded in Memphis, Tennessee was released in 1989, but Alvin Lee left the band to go solo in 1991. Another reformation of TYA took place in 1995 and the band toured South and North America. The reformation lasted until 1999 when a row erupted between Alvin Lee and Leo. Lee then went across Europe with Kim Simmonds’ Savoy Brown and during the tour realised “there was a hell of a lot of demand for Ten Years After”. Enter Ten Years After Now, rebranded but still pounding out the classics and newer material. He added: “We found two guitar players of our age and then Joe Gooch, who was a lot younger. We knew instantly that Joe was the right man for the band. In the first year with him we did more rehearsals than we’d ever done before. We also recorded a new album, “Now”, which sold phenomenally well.” That album was followed by a “live” double CD “Roadworks” in 2005 and a DVD and new studio album will be released in early 2008. And as for the drumming? “You get an inbuilt sense of time. You have got to develop that internal crotchet. Leo doesn’t play bass like many others who anchor the time. Guitarists tend to pull. It’s a great challenge.

“I think it is most important to play what the music requires. There are times when Joe is soloing and I stay off the double kick pedals, others when I really go for it. You’ve got to listen to and feel what’s required for the music that’s going on around you. “When Chick is soloing, for instance, I try to emphasise and be sympathetic to what he is playing. There’s lot of stuff that I can play but doesn’t really need to be in Ten Years After. It’s about exercising taste in what you choose to play, thinking about the audience, and working closely with your fellow musicians.”

Interview by Mark Forster