Rob Townsend

Rob Townsend is one of those drummers who have garnered less recognition than they should have done.

In fact, he fits the idea behind Mike Dolbear’s Drumming Icons to a T – celebrating those British drummers we may have forgotten in the headlong onslaught to praise American exports with their rows of toms, bass drums and cymbals galore.

Townsend fits neatly into the category because he’s an innovator, a class act who has been making a living from drumming for more than 40 years.

“I’m amazed I’ve been able to go on for so long,” he laughs modestly.

His dexterous, hard-hitting style propelled prog rockers Family to top ten successes in both the singles chart and long players.

But following its break up, he declined opportunities to really cement his name in pop and rock culture. He turned down an offer to join T-Rex, for example. There were others, too.

Nowadays he’s either bashing out the hits with The Manfreds or The Blues Band.

In between times he’s played a diverse mix of music, as a session man on punk tracks through to Peter Skellern, George Melly and on to Bill Wyman.

All the other British drum icons have said the sixties were great for musicians. How do you feel about that time?

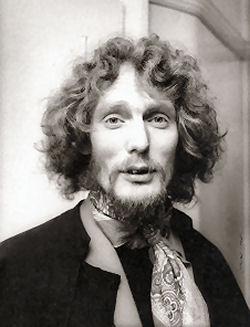

A very young Rob

“Family was fantastic,” he remembers. “One minute I could be Joe Morello; the next Ringo; the next Brian Bennett. Whatever you wanted to play if it felt right you were allowed to play it.

“With Family I got all my chops together. With Family I could do a roll round the kit and nobody ever said “hold back, we don’t want that”. I could do what I felt was right for the music. It was a joy for me.

“When it was all over and I got into session work I had to forget all that and play what people wanted me to play. I kept it simple.”

The Leicester-born Townsend found a passion for drumming inspired by a generation of American heroes.

“I had started playing drums from listening to a cousin of mine who had a lot of New Orleans jazz. Then I started reading the American drumming magazines. It was a great period for me.

“Then I saw The Gene Krupa Story. My parents went out and bought me a second-hand snare drum for Christmas. A gold glitter snare drum. Then I went and bought a hi-hat so I could play Apache. I also wanted to buy some toms so I could play Apache like Tony Meehan. In the end I built up to it.”

“In those days you didn’t have click tracks. You had to get it right.”

A Ludwig kit followed from Moore and Stanworth in Leicester. “Someone had bought it but couldn’t pay for it. Phil Stanworth came and saw me play and allowed me to buy stuff on hire purchase. So I bought it.”

But as much as playing, Townsend was immersing himself in watching and learning.

“I would go and see the shows at the De Montfort Hall, but if it was jazz and I could I’d sit behind the drummer. I saw Count Basie, Louie Bellson, Oscar Peterson, and Dave Brubeck with Joe Morello. It was just wonderful.

“Louis Bellson did the De Montfort Hall gig and a drum clinic at the Co-op. After he had finished the clinic I was able to get up on the stage. I’ve still got the newspaper clipping of me there, along with Brian Bennett and Eric Delaney.

“It was an amazing time. The Beatles had just brought out Magical Mystery Tour on film and Sergeant Pepper had been released.

“I was playing with various local bands in and around Leicester when I got asked to join Family who had just cut a record. In the 1960s there were many blues/soul bands. We had a sax player who had started off on mouth organ.

“A lot of musicians were trying to get away from the three guitars and drum syndrome and Family wanted to do that too. I was in graphics and had to leave work, much to the disgust of my mother. It was a reasonable job.

Rob with his Haymans…

“We started rehearsing. Half the tracks were blues and soul numbers and the other were quite obscure West Coast American band covers, tracks by bands like Jefferson Airplane, which were relatively unknown at the time.”

Building a reputation as one of the upcoming bands of the day, Family’s stage show, revolving around top-notch musicianship was beginning to pay dividends.

“We went to London to play The Marquee and The Roundhouse”, remembers Townsend. “Word had gone round about us. We had the first twin-neck guitar in the country – I remember [Eric] Clapton offering to buy it – we had a bass player who doubled on violin, and a sax player still playing harmonica as well.”

Another issue for Townsend to deal with was the astonishing rate with which Family lost bass players. Like a different take on Spinal Tap, he found himself paired with Ric Grech, John Wetton, Jim Cregan and John Weider.

“It was quite good because with John Wetton you had some free-form moments when he could just fly off. You had to go with him. Cregan was very solid and down to earth, so I had to go off on my own tangents.”

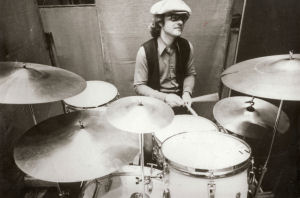

…and Rob with his DWs

Townsend’s kit was going through changes, too. “I started off with the basic four piece and two cymbals. With Family I went through the Buddy Rich stage – I had a little splash cymbal. Then later I went completely the other way, had two floor toms, lots of cymbals – especially smaller cymbals for effects – and lots of toms.

“I also played a 26 inch bass drum in Family. It’s pretty common now, but wasn’t then. The only reason I got it was that we went to America and saw my Ludwig bounce off the tarmac at the airport. Whether they dropped it or threw it I don’t know.

“I went to Manny’s Drum Shop in New York and told them I wanted a Ludwig bass drum. [John] Bonham had just got a 26 inch bass drum that he was using in England. They said they had a special deal as Ludwig had made two 26 inch bass drums. I had a beautiful blue oyster wrap on my original kit. This bass drum was canary yellow! We went to Woolworth’s in New York and bought some yellow sticky backed Fablon that you used to put on kitchen work surfaces for the rest of the kit.

“I remember everyone saying what an amazing finish they thought it was. Of course, the audience couldn’t really see it close up.”

Today, it’s DW all the way and Townsend plays 22″, 10″, 12″, 16″ kit with various snares.

“[In time] You learn what you need and what you can leave out,” he stresses. With a kit you learn to conserve your energy. Instead of hitting a cymbal up in the air you learn to put it somewhere that is more comfortable for you.

“[In time] You learn what you need and what you can leave out”

“I started getting back problems. One guy told me “look at your kit”. He was right. As a drummer you’ve got to play for two and a half hours at a time. You’ve got to set your kit up right. You’ve got to play it simple.

“I add things or take them away depending on whom I’m playing with.”

Townsend’s strengths with Family were his legendary time-keeping, his fluent approach and his enthusiastic and energetic hitting. Little has changed.

Leading Family through a myriad of time changes in a single song meant Townsend had to be on top of his game time and time again.

And then it all ended. A gig at the Leicester Polytechnic in October 1973 brought the curtain down on Family after seven critically acclaimed albums, top ten hits and appearances at major festivals, including the Isle of Wight and also supporting The Rolling Stones at their historic 1969 Hyde Park concert.

Townsend wasn’t short of offers and agreed to join Medicine Head and the hits followed.

At this time, he turned down an approach to join T-Rex with Marc Bolan. “The choice was pretty simple for me,” remembers Townsend. “I had already accepted Medicine Head. I had already started rehearsing with them. I discussed it with my wife and she said I should do whatever made me happy.

“I didn’t take some offers that would have kept me on a higher profile. Do I have any regrets? No. I’ve made a living playing.”

But when Medicine Head decided to return to being a duo, Townsend jumped at the chance of session work. From fame and relative fortune in Family, and having been told what money he could have been on if he had joined T-Rex, his first session was for British Gas.

Rob today

But Townsend, with typical good humour, says that session work was a “really good learning experience”. “In those days you didn’t have click tracks. You had to get it right. I did everything. I did punk sessions, then I got the Peter Skellern gig. I remember they went round handing out the music. I didn’t read music. So they put “stop here”, “start here” on it for me.

“In sessions you play for the song and I’ve always been inspired by songwriters. Peter Skellern is a very talented musician. He had tried about three drummers, but his producer had wanted a rock ‘n’ roll drummer. I did the album.”

Hold Onto Love was a top ten single success for Skellern and Townsend. Sessions with Tom Robinson, Bill Wyman, Scaffold and George Melly followed, along with Duane Eddy. “For a while I was a reggae drummer, too”, Townsend laughs.

Then a new door of opportunity opened and the Blues Band came a knocking. “I had turned them down before,” remembers Townsend. “I remember driving past this place and there were huge crowds queuing to get in. That was a Blues Band concert. I thought, “this is perfect for me”. But I had to audition to get in. I’ve been with them for 25 years.”

The Blues Band, which was comprised of former members of Manfred Man fronted by singer and broadcaster Paul Jones. The Manfreds reformed about fifteen years ago including all but one original member plus Mike D’Abo (who replaced Jones in the original band).

Townsend has never looked back. “It’s great fun. I’m playing with extremely talented musicians, nice guys. It’s just so enjoyable.

“I’m still playing. I haven’t stopped. When Family broke up a friend of mine, a jazz trumpeter, asked me “what are you going to do now?”

“I said I didn’t know, but he said “no, go out and play”. He said it was a question of whether I wanted to be a musician or a “face”. I only ever wanted to be a drummer.”

Words: Mark Forster