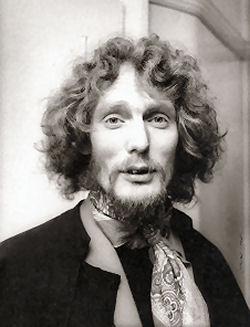

Simon Kirke

If anybody were to ask me what records I would have liked to have played on – right up at the top would be Free’s ‘Alright now’. Simon Kirke and I have often bumped into each other by accident at various watering-holes but this time we were meeting by design. Simon was here doing a few gigs before Christmas and I drove up the M1 to talk to him before a gig at Wavendon.

You don’t live here in the UK anymore; do you live in New York?

I live in Manhattan; I’ve been there since 1996.

Do you like the buzz of Manhattan?

Yeah, I did. It’s lost a little bit of its allure now, what was once exciting is now a bit noisy, as I get a bit older. I like America. It’s a little more easy going. I’ve always liked the Americans – I’ve toured there year after year and I got to know the way of life and got to like it. I’m not particularly mad about its politics sometimes but now that Obama’s in I think that’s all going to change.

God willing! The alternative wasn’t really worth contemplating was it?

No it wasn’t. I was fully prepared to move back

That would have brought you back?

Well, it would have made me very uncomfortable, so I think the right guy is in. But I like Manhattan, I’m not saying I’ll be there for the rest of my life; I do miss parts of England, aspects of it.

Things like football, that sort of thing?

Yeah, you know what, I miss the charm, the politeness, I miss the atmosphere of the country. I’m not mad about London anymore; London to me is not England. Here is England, the Home Counties. I just drove down from Leeds today, I went through the Yorkshire Dales, and it was gorgeous. You take the cards you’re given, don’t you.

With a Swiss Army Knife we dismantled an entire room at the Park Lane Hilton, cut it all to bits and put it in the chest of drawers there, hoping they would never find out.

That’s true. Was it a career move when you went?

No, it was family. We came to a point where the kids were starting to grow up. We were tired of England, it was when John Major was in power, it was very dismal and I felt I could get more work in America, which actually wasn’t the case. Bad Company soldiered on for a bit longer but then I got really into drink and drugs and by being in America that helped me kick all that. There were meetings everywhere.

So this is AA?

And NA. I’ve been sober now for 4 years, on and off. My period of sobriety now is 4 years but I’ve been in the programme about 20 years, in and out. Taking lessons really from Eric Clapton, who’s the patron saint of all of us, God bless him! I took a lot of leaves out of his books. Yeah, it’s the way I am now, I’m quite happy with it.

Are you spiritual as well?

I am, yeah. I find a lot of comfort in music of course, [but] I have to have a higher power. I say my serenity prayer most days, pretty well every day.

I’m a drummer, I’ve been there. I’ve done more American tours than I’ve had hot dinners, so over the years it’s something that happens.

Boredom.

Exactly, it’s the same as hotel wrecking really. I don’t know if you’ve ever been there?

Oh yeah. I remember me and Jim Capaldi, God rest his soul! I miss Jim. With a Swiss Army Knife we dismantled an entire room at the Park Lane Hilton, cut it all to bits and put it in the chest of drawers there, hoping they would never find out. They were very good about it, they just billed my Platinum American Express £1000.

That’s not bad, is it – a grand for a whole room?

Not bad.

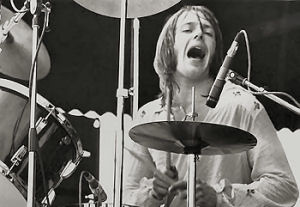

Lets go back to the beginning then, how did you get into drumming?

Well I was brought up in a very Spartan lifestyle, no electricity, no running water, no indoor plumbing. It wasn’t until we got electricity when I was about 12. We moved to Totteridge, got electricity and got a TV. One of the very first programmes I ever saw, black and white of course, was a thing called ‘All That Jazz’ hosted by Jack Parnell who was a very good drummer in his own right, [played] big band jazz, and I was hypnotised by this drummer whose name I believe was Douggie [Wright?] or Jackie Coogan. I was spellbound by what he was doing. It was a form of music I’d never heard before.

I’d listen to Radio Luxembourg, Animals, early Beatles, Stones, I was never really enamoured by drums then, just overall music [itself]. But seeing this, shiny cymbals, lovely drums – he had a huge kit – Eric Delaney was on and something took hold of me. I picked up a pair of knitting needles of my mum’s and there was one of those three bar fires with a grill and I started tapping, and I actually touched one of the elements and got a shock. Then I carved sticks from the hedge, I had no idea what sticks were, they were about 7” and started banging on various books of different thicknesses.

How old were you then?

Twelve. When I was thirteen I got my first snare drum. I still remember it. It had a little splash cymbal on an L-arm that came out from the snare stand, a pair of sticks and some brushes, which served me well. I love brushes.

Do you still use brushes?

Sometimes, I love them. Not the hot rods, I’m not mad on them, but brushes – lovely sonic texture. But that’s how I started and then my biggest ever leap forward in learning came by way of our school bus driver and his name was Mr. Lane. By this time I had a little kit called a Gigster in Red Sparkle. He heard that I played drums and he used to have a local discotheque. He used to go round all the village halls and play the 45s of the day and he came up to me one morning as I was getting on the bus and said ‘I hear you play drums, how would you like to bring your kit along on the stage with me? I’ll play the songs; you play the drums to them.’ I was stunned; I was shit scared by the way. I did that for two years and it gave me a very good sense of timing because I had to play in time. I was playing Jim Reeves stuff, then we’d do the Supremes, then Can’t Buy Me Love, then we’d do an old Valeta or Waltz, it was the whole smorgasbord of the day.

Buddy Rich. He did and he still does [knock me out] whenever I see him on YouTube. He’s phenomenal

What did it sound like?

Well it must have been pretty good because we kept doing it and getting return bookings.

Well it must have been pretty good because we kept doing it and getting return bookings.

So it was regular records and you were playing along?

Yeah. I remember him saying ‘We’ll give you a trial’. Because I don’t think even he thought it would work. I was a little schoolboy and I think he thought it would be something to bring the punters in and it worked – for two years. Then of course I wanted to be in a band. Someone saw me playing – Richie Jones. He had a band called The Maniacs which I always thought was a great name for a band and he asked if I would like to play drums with them. I was about fifteen by then and I was interested. I met them; we were playing all sorts of covers. It was a regular band, a five piece. It’s the only band I’ve ever known that had a 10 input amp and we used all 10. It was the size of a small kitchen table but we used it. Of course I had to ask my parents because my school work was starting to suffer. I was playing Friday, Saturday and Sunday until about midnight, maybe 1 o’clock. Sometimes I’d have a mid-week gig with Mr. Lane. So my school work was suffering a bit and my mum and dad said we’d give it a few months and see how it goes. They could see I was enthusiastic about drumming.

What sort of year are we in?

Well I’m 59 now, so 1963, and the Beatles kicked in and knocked me out.

Who had knocked you out before that? You mentioned Eric Delaney and Jack Parnell. What about American Jazz drummers?

Buddy Rich. He did and he still does whenever I see him on You Tube. He’s phenomenal. Brian Bennett, out of the Shadows, because he had one of the first drum solos. I think probably the first drum solo I ever heard was Little Bee by Brian. I haven’t heard it since, but it knocked me out then. He had a jazz grip so he could do Mammy Daddy stuff and it sounded like God. I mean, now knowing how to do it, you know, it aint that difficult, but of course it was 50 years ago.

If you were asked to categorise yourself, I assume you would say that you are steeped in R&B?

Definitely

In those days my number one governor of all time was Al Jackson. I was absolutely flummoxed by what he did, so simple, yet so solid. For me… I absolutely adore his playing.

Not modern R&B, I’m talking about the obvious ones from the late 50s, early 60s. So who did you listen to in those days?

In those days my number one governor of all time was Al Jackson. I was absolutely flummoxed by what he did, so simple, yet so solid. For me, I’m not saying for anyone else, but for me, I absolutely adore his playing. Benny Benjamin from the Motown guys, Uriel Jones, Earl Palmer, who was not much maligned but very underrated. He played with his snare drum at 45º and used that jazz grip. When he played the snare drum, what a back beat!

Is this where the whole ‘pocket’ thing came from for you?

Well I’ve got to tip my hat to Ringo and Charlie. The early Beatles stuff I think was better than their later stuff in terms of sheer playing. With four tracks remember, they had to play tight. Ringo was a fantastic song drummer. Even he will admit he was never a great technician, but his pocket, his feel. Charlie Watts was the same – wonderful – and he was the first guy in rock I saw using a jazz grip.

Levon Helm was another. When Levon came along I’d never heard drumming like this. Paul Kossoff adored Levon. It was funny that, he turned me on to The Band. Ginger Baker is at the other end of the spectrum because he had the bombastic style. I’d never seen drums played like that, a double kit, but I loved Ginger’s attack, he was such an innovator.

He changed the music

Without him, without any of them, Queen just wouldn’t have sounded the same. But Ginger was a pain in the arse sometimes!

So was Levon Helm an influence as far as Free was concerned?

Yes. Well you see Free was split down the middle in the early years between me and Koss [Paul Kossoff], who were into strict Blues guys along with Otis Redding, Stax and Motown, and Paul Rogers and Andy Fraser who got a hold of [Music from the] ‘Big Pink’ and were absolutely thrilled by it. They kept saying ‘Simon, try playing like this’. I hate being told how to drum, it’s a weakness but they were saying ‘Do this, do this like Levon’, and for about a year me and Koss were always on the other side. I refused to get into the Band and eventually of course I became a convert and I’ve adored them ever since. But Levon’s playing is just lovely. ‘Chest Fever’ is lovely. I learned from him and believe it or not from the James Brown drummers, Stubblefield and Starks. It’s the touch, that’s what Levon and them have in common – a lovely delicate touch when they needed it, it wasn’t just muscular backbeat.

This muscular backbeat is without a doubt a product of stadium rock in my opinion. You have to get that offbeat in and you have to sacrifice technique to be heard. There’s generally no point doing doubles. There’s definitely an element of less is more in stadium rock without a doubt.

That’s what I learnt. But I learnt pretty bloody quickly as far as Free and Bad Company were concerned ‘we had to play together’. Power does not necessarily come from volume, it comes from playing together. We played to huge crowds in those sweaty clubs, The Marquee, those clubs that could only hold 400 but they put 600 in, you had to play in a certain way. We didn’t want to blast them, we wanted to overpower them and we could only do that by playing together.

But when we went to the States, my first gig in the States was Madison Square Gardens with Blind Faith, and four little kids walked out. Free were opening the bill, I hit the snare drum and then the bass drum and that’s when I had to learn on my feet.

I forgot to mention Aynsley Dunbar who I loved, I was a big fan. He married jazz and rock very well.

He played in a jazz band didn’t he, so did Ginger and Mitch, but when Aynsley arrived with Frank Zappa I was surprised. But then I thought ‘Why not?’ When you consider you’d go and see his first band, the Mojos and his drum solo was ‘Take 5’. How over the top was that? Everyone else was struggling in 4/4 and there’s Aynsley doing it in 5/4.

He played in a jazz band didn’t he, so did Ginger and Mitch, but when Aynsley arrived with Frank Zappa I was surprised. But then I thought ‘Why not?’ When you consider you’d go and see his first band, the Mojos and his drum solo was ‘Take 5’. How over the top was that? Everyone else was struggling in 4/4 and there’s Aynsley doing it in 5/4.

Its funny you should mention that and I’m glad you brought that up. When I saw Cream a few years ago, I saw the reunion tour at Madison Square Garden, Ginger did his obligatory solo in 6/8 and it was a revelation, because to play in 6/8 frees you up. The very few times I do solos now I do them in 6/8, it swings without being tied. But that’s interesting that you said that about Ainsley.

The other thing I heard Dom Famularo solo in 12/8 there was so much room for inspiration and it was just fantastically soulful.

It’s a lovely rhythm.

But getting back to those influences, we’re talking about mid to late 60s, and I was pretty formed in my influences that Jackson was the number 1 and then there were others that I learned from. I loved Carlton Barrett with Bob Marley and the Wailers. We were with Island Records and we saw Bob Marley a few times, Carlton Barrett was wonderful, I couldn’t do that stuff. You just had to be born and raised in Jamaica.

Exactly. I don’t know if you ever tried it in a studio. You get booked for a session and they want you to play reggae, and you think hang on a minute there’s loads of stuff I can do, but somebody else does reggae and it isn’t me.

Yeah, I can only do the bass drum on the offbeat, all the stuff in between I’m lost.

Again, that epitomises less is more.

Then I heard the later Motown drummers with Marvin Gaye, they did an album. Jim Capaldi was a great friend of mine, a great influence; he was like an older brother. I remember him calling me saying I had to go over to his house, he lived in Marlow, ‘I’ve got an LP that’s knock you out’ and it was the one after ‘What’s Going On’, but it had Uriel Jones, Pistol Allen, doing solos, I was floored, these guys were so good. The fact that I was sharing this experience with Jim made that moment very special.

So we tried it [Alright Now]around the country in various guises, we rehearsed it, playing it for the crowds, it went down a smash. I started it with 8s on the hat, but I never really got into in until I started it on quarter notes

Did you know Marvin was a drummer? He played on a lot of early Motown stuff. What is great is their touch; they weren’t playing through the snare drum. In the 60’s the English way of doing it was to play through the snare drum.

You mean hit hard?

Yeah, but playing through the snare drum. I’m sure they were playing like that; it was a completely different sound to not hitting hard.

I’d like to ask you about ‘Alright Now’. Was that a studio arrangement?

Well all of our stuff was a studio arrangement.

Right, it was all got together in the studio?

No, Andy and Paul would come up with the basic idea; we needed a dance song because our early Free stuff was very pedantic. It was good but it loped along, there was nothing to get up and bop around to and we needed a song like that. So we tried it around the country in various guises, we rehearsed it, playing it for the crowds, it went down a smash. I started it with 8s on the hat, but I never really got into in until I started it on quarter notes. I learned the value of quarter notes on the hi-hat from Ziggy Modeliste from The Meters and something just clicked in my head to do it in quarter time and it just started to swing along. The only bit of arranging we did came from Chris Blackwell, head of Island [records], who lived above the studio. The engineer was so excited about the song that was coming out of the speakers that he said ‘I’ve got to get Chris up’. So he came down and he said ‘It’s good, but it’s too long, it needs an edit’, of course he did it and the edit is not very good. It was five and a half minutes that he cut out. So that’s the only arrangement that we did.

Everybody plays ‘Alright Now’, you’ll be in a band and someone will turn around and say ‘Alright Now’. And we’ll all play it. We think we know how it goes but when you listen to the record it’s a very well worked-out part. I’ve heard so many guys not get it quite right, not understand it, and as you say it comes from the 4 on the hi hat.

What throws most of them is the solo because it’s really quite easy to play up until the solo. The solo is one of the best solos ever put down and in one take I might add. There was nothing snipped and pasted together. So that really throws most guitarists. It was just a happy song.

It became a bit of an albatross to be honest – it buried us. Suddenly on one hand it opened up all these avenues, we started playing different countries, went all over the world with it, then we had to come up with another one like it. Island Records loved the commercialism of it – it was the biggest song Island Records ever had.

So we had to come up with something else, something akin to it. We were very idealistic, we’d have a good run with it, we’ve done that, we want to do what we want to do. So anything that came after that, it was The Stealer by the way, died a death. After that we broke up. We broke up after ‘Highway’, Kossoff got strung out, we got back together for him to get him straightened out, we did ‘Free At Last’ and that was the last album we ever did.

As far as Bad Company was concerned, if you had to pick, was Free your happiest body of work? I don’t really know how to ask this.

As far as Bad Company was concerned, if you had to pick, was Free your happiest body of work? I don’t really know how to ask this.

I know, exactly, it’s a dilemma. Free was very painful but the initial success was wonderful, that’s what we got into a band for, we were four little guys, we ruled the world, playing great music, we were going down a bomb, we’d never done it before. You see Bad Company was Free on steroids, we were a huge band, and we had marvellous success. But going back to Free it became painful, Kossoff got strung out, we’d cancel tours in the middle of tours, promoters wouldn’t book us, it was a nightmare and we just said ‘f**k it. Money was being lost, money was being owed’, so we broke up and out of the ashes of that band, we and Rogers kept in touch, we always got on fairly well.

But in answer to your question, both bands were very rewarding for the first couple of years and then it becomes a bit of a grind. Free was our little gang so I would say the first big success we had in that band meant the most to me. We never got any gold records with Free; we got one for ‘Alright Now’, but none of the albums.

So you had to wait for the first Bad Company albums.

It’s upwards of 12,000,000 now.

Is it?

It’s a Diamond Album.

They call them Diamond Albums now?

Yeah, anything over 10,000,000. We’re still waiting for it, RIAA by the way!

So what have you got on the horizon, where do you want to be? Won’t you be getting a bus pass next year?

Yeah, it’s hard to believe. Well as I said I quit drinking, I look after myself, I do yoga, I keep fit. What would I want to do? I write songs, I do these solo shows now for sheer amusement and enjoyment. I do acoustic shows and I am actually going around with this Free tribute band who are really very good – I’ve played drums with them for the last couple of songs. I write songs, I teach drums in New York. I like teaching people, I teach any age.

I started on the recorder at school – like all of us. But drums are my first love.

Are these master class type things?

Kind of. I don’t teach reading. I don’t read, but I will help you with your feel, soloing, time keeping, which I think covers just about everything. I’m doing a project with a singer who I can’t tell you, but he’s quite well known, and that should come through next year, so I’m keeping busy.

And I still love drums, drums are my first love. I was interested to read that Al Jackson Jr, my Number 1 guru, played piano and other instruments as well, which was unusual for drummers in the early 60’s.

Do you?

Do I play piano? Yes.

You started on the piano?

No, I started on the recorder at school – like all of us. But drums are my first love.

Do you collect them?

No, I never got into that.

Would you say that Hayman sound characterised you at that time?

Its funny, for a start the recording techniques for drumming in those days was very sparse and primitive. If you blindfolded me and played me one album and then another and asked what drums I used, I couldn’t tell you. I just know a well tuned kit will sound good whether it’s Sonor, Premier, Ludwig, or DW. But most kits today, if they’re well tuned, they’ll sound great. I can’t say that any kit characterised my sound in those days, although I played a Super Classic on ‘Alright Now’ and the Hayman I played on three albums after that. I always wanted it to be louder. I remember going into the control room thinking it sounded a little puny, this was in the days before the outboard gear.

I’ve got to mention Bonzo who I adored, but his sound was achieved by, obviously a well tuned kit beautiful played. But Jimmy Page had these ambient mics left and right and he had a whole channel for the ambience pulled right up to infinity so he got that lovely sound. Free came a little bit short of all those innovations, but Bob Clearmountain did some mixes about 10 years ago and he pulled it out, it sounded a lot better.

When did that come out?

That came out about 10 years ago. I think its called ‘The Free Story’, about 20 tracks from Free, all re-mixed. He did a good job.

It so different now in as much as the snare drum in the 21st Century can go ‘zoing’, where in the sixties we couldn’t get away with that. ‘You’ve got to get rid of that ‘zoing’, where’s your tea-towel?’ Were there any tea-towels in evidence with Free?

No, Carlton Barrett used a tea-towel and Ringo did. I hated it, I feel it emasculated and muted the drum and it was awful. That’s why I loved Bonzo, he had no damping. He was totally the other way. But you had to made sacrifices for the recording. They always said take the drum head off on the bass drum which I hated – the feel goes. Then the single-headed toms came along which I didn’t like. [Talking of which] another good drummer is Phil Collins.

Absolutely, and Phil did like single headed drums. All those concert toms.

And I’ve got an old Gretsch kit which I adore. I’ll tell you a quick story. I went to see Charlie Watts several years ago, he said ‘Here Simon, I’ve got some new gear’, I said ‘At last!’. He took me into the studio and there was the same old brown Gretsch kit which is older than stone, and I’m looking around thinking ‘Where’s the new gear?’ and Charlie said ‘I’ve got a new pair of sticks and a new ride cymbal!’

Interview Bob Henrit