Warren Cann

He’s the drummer behind one of the most recognisable beats in music history.

He’s also one of the pioneers of electronic drums, a visionary who saw the potential behind the odd-looking boxes of tricks and explored further, always pushing the boundaries.

Yet Warren Cann appears to have been overlooked for his contribution to music. With some B-sides, he was coming up with what would become the norm in techno, drum ‘n’ bass (or in this case drum ‘n’ synth) and rave music years later.

He was the driving force in the critically-acclaimed early incarnation of Ultravox! (the ‘!’ was dropped after the second album), with John Foxx as lead singer, and then the reinvented Ultravox with Midge Ure as frontman.

And in April 2009, for the first time since Live Aid in 1985, he will take to the stage with a reformed Ultravox for a sell-out UK tour.

“The reaction from people around me has been “Are you excited?”, he laughs. “No, I’m concerned. Once things are sounding right and I’m out there, then I can get excited.

“We all got an e-mail from Chris O”Donnell [one time Ultravox manager] about eight months ago. He said the feeling in Britain was that it would be a very good time to think about getting back together for a reunion tour.

We got in touch with each other and said ‘Why not?’ That’s how it came about.”

And it gives the Los Angeles-based sticksman another opportunity, or 16, to play that drumbeat – ‘Vienna’. With the thunder-style answer to the simple bass drum call it helped create an atmosphere which might be hackneyed now, but was groundbreaking at the time. There had never been anything like it, and arguably, certainly in terms of drum patterns, there hasn’t been anything like it since.

“It didn’t occur to me at the time, but I own that pattern. It was different and nobody had done it before. As a drummer there were certain patterns, like Charlie Watts on ”Get Off Of My Cloud” or Ringo on ”Tomorrow Never Knows,” that were just so special and memorable. I had always thought I would love to come up with something like that.

“When we wrote ‘Vienna’, I think it took about two hours. Half the song we already had; we had this thing floating around that we were trying to put in a song, but so far hadn’t found the right niche.

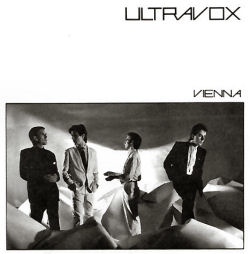

Vienna… THAT drum pattern

“I had that pattern. It was electronic and it was percussive. I was messing about with a small electronic percussion unit called a Synare III. You”d have heard it on some disco records, and I can’t tell you how much I hated that noise, but by playing around I came up with the thunder sound, all rumbly and rolling. It was exciting. I blended it with the kick and snare pattern I wanted to use and played it to the guys, just put it together and said ‘How about it?’ They just instantly fell into it and we had the song in a remarkably short time.”

And after the ignominy of being dropped by their previous record company, despite critical acclaim and a successful, self-sponsored tour of America, Ultravox was suddenly being noticed.

The Vienna album yielded five chart-placed records and appearances on Top Of The Pops. Aside from the frustration of the innovative title track ultimately being kept off the top spot by a novelty record, Cann and Ultravox had finally arrived.

But Cann is arguably one of music’s unlucky heroes. He could have been a household name, yet was always at the front of musical revolutions, never quite riding the crest of the waves which followed.

Born in Canada to British parents, and proudly British, Cann arrived in London as a teenager after playing grueling sets in Canadian and American strip clubs similar to the Hamburg scene which had been a fertile apprenticeship for The Beatles and dozens of other British groups musically.

“We were playing everything from the Top 40; Beatles, Stones, Who, Yardbirds, Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, Wilson Pickett and Joe Tex when it was still new, when it hadn’t been played relentlessly for 40 years,” he recalls. “It honed my chops pretty early on.”

But London was a different experience. He hooked up with future Hawkwind guitarist Huw Lloyd-Langton and encountered sundry colourful characters in London”s scene before linking up with his future Ultravox! bandmates in Tiger Lily. Fame came with a cover of Fats Waller’s ‘Ain’t Misbehavin’ which was used as the title music to a porn movie. It was a paying gig which allowed the group crucial studio time and the chance to record their own song for the B-side.

Inspired by drummers like Ringo Starr, Charlie Watts and John Bonham, as well as Keith Moon and Ginger Baker, Cann proved his versatility on vinyl and live. Witness his frantic, ultra-fast playing on ‘Fear In The Western World’ and ‘Distant Smile’ on Ha! Ha! Ha!, Ultravox!’s two finger salute to the critics, or his measured and mesmeric playing on the Roxy Music-inspired ‘Dangerous Rhythm’ from the earlier Ultravox! album. Cann was a musician for all occasions. He even took lead vocals on ‘Mr. X’, an album track on Vienna, and ‘Paths And Angles’, which was a B-side.

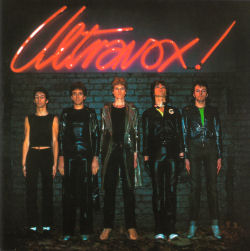

Early Ultravox!… complete with the exclamation mark

He was an early exponent of drum machines. He was one of the first musicians in the country to get hold of Roland’s TR77, then the ground-breaking follow-up CR78, plus the first Simmons drums and the first Linn LM-1.

Typically, Cann had harnessed the effects of these rhythm boxes for one of the classic John Foxx-era Ultravox! tracks, ‘Hiroshima Mon Amour’, but it would be left to another drummer, one Phil Collins, to make the world sit up and notice the drum machine on his hit solo offering ‘In The Air Tonight’.

Cann was blazing a trail for others to follow. He was proving what could be done, pointing the direction for others. “We were always ahead of the curve,” he says philosophically. With John Foxx, Ultravox never had a hit, but others inspired by the group were hit-makers, most famously Gary Numan.

Playing-wise, Cann’s flirtation with technology was to lead him in a different direction, shedding the rock drummer persona to become a metronomic master. Playing along with precise computerised rhythms proved a different challenge to simply locking with a bass player.

“There’s more to it than meets the eye,” he admits. “It’s harder than playing ”freeform,” for want of a better term. Depending on how you look at it, though, you might as well be playing to a click track.

“I hate playing to click tracks because when you are right on the click, it disappears. But I loved playing to pre-determined bass pulses. You’ve got to be there with good meter and not just in there, but be comfortable and play with feeling. It’s like playing with a super accurate bass player. Of course, the true element of fascination with these machines was that no-one had heard perfect rhythm before. It did not just improve my time-keeping, it improved everybody’s time-keeping.

“I’ve always admired simplicity. Some drummers want to hit lots of things because they can, but then you look at what Ringo and Charlie Watts were doing. My idols were simple but brilliant players who made magic. They weren’t setting out to prove anything. It was all about playing for the song.”

Cann’s interest in machinery and technology went far beyond what was commercially available. He tinkered with the circuits inside the strange-looking boxes to get new and different sounds. He altered factory presets beyond recognition and took the technology to its limit – and sometimes beyond. And not always with the blessing of the companies or their agents. “Roland kicked me out of their lab and yelled at their tech guy when they realized my CR-78 wasn’t actually faulty – we were hot-rodding it.”

“When I started using a drum machine we wanted to experiment with this totally new technology. It was new to us and new to a hell of a lot of people. Things happened. It brought to our attention psychological aspects we never expected. In rehearsals because you were not in ”real time,” you could experiment and find an absolute knife-edge tempo whereupon everything in the song balanced just perfectly, but it was always a nightmare to try and find again.

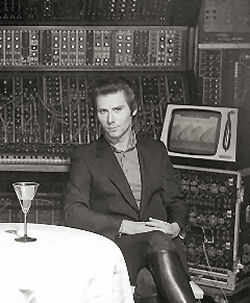

Warren with the Fairlight and massive modular synth

“In those days it was incredibly difficult to reproduce the same effect or sound twice. I hacked into a machine and used a cheap LED multi-meter which I set to read a DC voltage linked to the clock circuit. The read-out numbers mean nothing as far as BPM was concerned, but that specific voltage related to the timing of the clock – so I could set my tempo to match a given number and the speed would always be the same. Quick and dirty tempo display! I also wired in a separate potentiometer, which allowed me to fine tune the tempo. I had to, as the usual speed controls were always so coarse on those things that if you even looked at it sideways, the tempo jumped a mile.

“At one gig I started off the machine and it sounded like it was at totally the wrong speed. I got dagger looks from the rest of the band. But it was the right tempo. It just seemed slower because our adrenalin had kicked in. Just one small example of things to digest as we delved further into what drum machines could do.”

Cann put the sounds he was making through a guitar amp, and through guitar effects pedals. “In the studio I”d already been running my acoustic kit through various distortion units, so this step was a natural.” He also found a way to send the sound through a Moog [synthesizer] and then managed to come up with a sequencer-type box which could come up with complex and accurate patterns. Eventually these formed a bass line which linked in with Cann’s own drum machine or alongside his acoustic drums. The bass pattern on hit single The Thin Wall is an example of the bass patterns Cann could manufacture with Ultravox bassist Chris Cross.

“This was in the days long before MIDI. We were pushing the envelope and it was quite frightening live. We were all up to our ankles in wires and bits of kit and ended up requiring our own tech-engineer to take care of the machines.

“On one tour I had a tower next to my acoustic kit. It contained three different Simmons units – an SDS3, SDS5 and SDS7 – plus a Roland TR77 and CR78, a Linn LM-1, a LinnDrum, a Sequential Circuits Drumtrax, various FX units like a Roland Space-Echo, and completed by a 16-channel mixing desk and power amps. As it was pre-MIDI, I had to use five or six different drum machines. There always seemed to be a feature in one that you didn’t get with the others: so, if we”d written and recorded a song based on a particular aspect of that drum machine, then I had to use the same thing for live.”

At one early gig, the audience were unsure what Cann was doing in the background, having vacated the drum stool on his acoustic kit to put a drum machine through its paces.

“Someone asked if I had been reading a book,” he laughs. “I immediately got rid of all the MDF cases with vinyl woodgrain and stuck the TR77 into a clear Perspex case with lots of little LED lights that flashed. I went from reading a book to being the mad scientist on stage. Much better.”

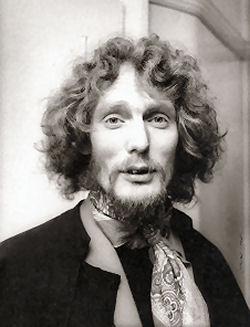

Original publicity shot…

The Roland CR78 was a huge improvement on the company’s first offering, the TR77, and the user could actually program a rhythm of their own. But Cann wanted more. He opened up the machine and took a tiny non-conductive screwdriver to its insides to get more sounds. “The sounds were made by analogue circuits, so you could tweak values which would have an effect on the sounds.”

“Drum machines have now been assimilated into music so much that no-one thinks anything about it, but we were having fun and I was always experimenting. On our first tour to America in 1979 I had one of the very first gadgets from Dave Simmons whom at the time was working out of the back of the record shop he ran in High Barnet. It was called a ClapTrap, a metal case with knobs on it and about the size of a small box of chocolates. It was pretty much a one-trick pony as all it did was create handclaps.

“It was crude but brilliant. I would keep it under the heel of my left foot, and using heel-to-toe onto a non-latching footswitch could get handclap sounds while I was playing.

“The reality was that because we modified stuff so much to make it do what we wanted it to, they were difficult to fix and impossible to replace if anything went wrong. Which put us in the very vulnerable position of having one-off equipment. Plus, I wasn”t using this stuff in the safety net of a studio, I was using it all live.

“If it went bad on stage, you couldn’t do much. Perhaps if we”d only written one or two songs around the machines it wouldn’t have been so bad, but we had written the majority of our songs around them in one jigsaw way or another.

“Consequently we were very focused. This meant we got a bit of a reputation for being po-faced onstage, which we weren’t. Privately, we were anything but.

“We eventually finessed it to the point where things weren”t quite as liable to melt down, but there was always a large element of luck involved. When we did Live Aid we were trying to enjoy ourselves, but were also aware something could go wrong at any moment. We were just praying the equipment would hold up.”

In 1980 Cann expanded his musical horizons by hooking up with future award-winning Hollywood composer Hans Zimmer in the project Helden. This included a critically-acclaimed series of performances at London’s Planetarium using multiple then cutting-edge CMI Fairlight synthesizers. The pair had initially worked together via The Buggles, which resulted in the chart-topping ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’. “I just went along as a bod and played drums on Top Of The Pops for them! I played on ‘Living In The Plastic Age’.”

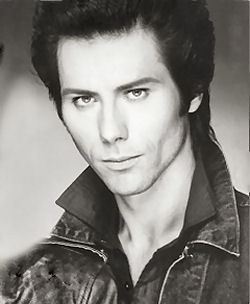

… and with the modern graphics for the Best Of…

“Ultravox was becoming more commercial with every album,” he remembers. “Helden was more of an outlet for art. Hans and I were determined to go in exactly the opposite direction from any conventional music-biz way of doing things. On reflection, I suppose we were our own worst enemies. Our gig at The Planetarium was pretty “out there.” In the studio with Helden, we”d found when we muted all the faders for the conventional instrument tracks, the remaining synth tracks of strings, brass and percussion were virtually classical music. So, just for the Planetarium shows, we decided to turn Helden”s songs into classical pieces. We did it just the two of us. Although Fairlights were rare and extremely expensive, we had some connections and managed to borrow Kate Bush’s and John Paul Jones’ plus a couple of others that were in the country.

“The gig was successful, but we did ourselves out of a record deal by saying we would have different singers and musicians for each album. Record companies didn’t see sense in having a hit record and then changing the line-up… what a surprise. Reps said the gig was phenomenal and amazing, but there was no offer to back it up.”

Meanwhile, tempers were fraying in Ultravox and after the Live Aid performance Cann was told he was no longer wanted. “I was fired. Things were coming to a head between Midge and I. We were all burned out. We were all frazzled. In those circumstances, everyone says and does things they regret later.”

Cann linked up with The Sons Of Valentino, but quit drumming and left to pursue playing rhythm guitar and keyboards. He again played with Huw Lloyd-Langton in this new capacity and later relocated to Hollywood in the hope of following in the musical footsteps of Zimmer. He scored a few low budget films and ended up writing a few scripts and enjoying a few acting roles before stepping out of the public eye – until the Ultravox reunion call came through.

“I’ve got a rehearsal studio that I go to and play along with the tracks,” he reveals. “That’s been working out well. When I’m not doing that I’m busy programming.”

The one-time Ludwig player will be playing a Yamaha Oak Custom, paired with Zildjian cymbals. And it will be a different kettle of fish to the days when programming a drum pattern for one song could take many hours of painstaking computer wizardry.

“On one tour, I calculated that, in total, the amount of time I had to just relax, look out into the audience and enjoy the gig was about 15 seconds. Not in one chunk but over the span of the gig, because I was always busy playing or programming for upcoming songs or both. Sometimes I had to keep the rhythm going one-handed while I hit switches with the other to prepare for an upcoming song.

“It’s going to be quite different this time. I shall be using a Yamaha DTX Extreme and a MacBook Pro, with sampled sounds. I will be a little more relaxed.”

Interview – Mark Forster